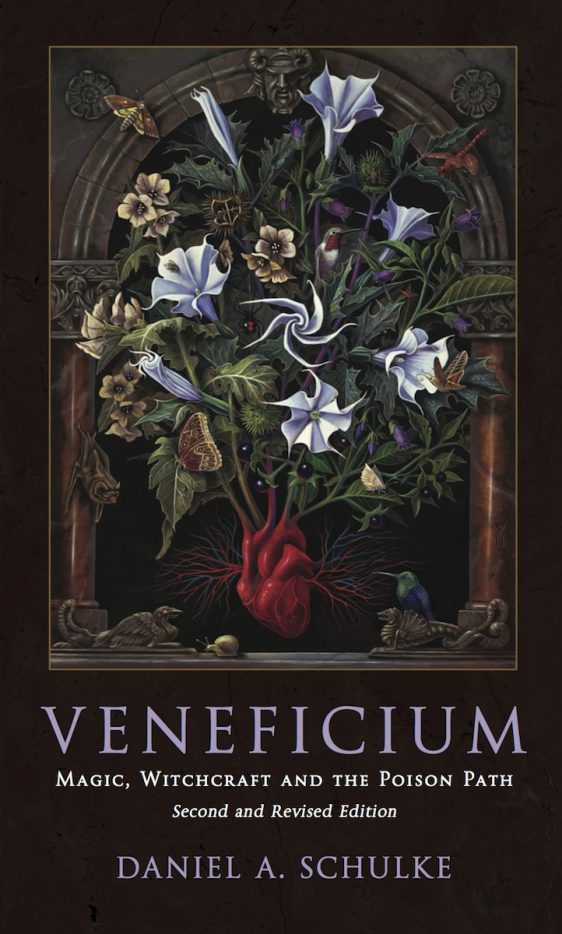

Originally published in 2012, this is a second and revised edition of Daniel Schulke’s book on botanically and venomously-focused witchcraft. As the promotional blurb goes, this second edition contextualises Veneficium within a new trilogy of forthcoming books entitled Triangulum Lamiarum (‘Triangle of the Witches’); no word yet on the other two titles.

Originally published in 2012, this is a second and revised edition of Daniel Schulke’s book on botanically and venomously-focused witchcraft. As the promotional blurb goes, this second edition contextualises Veneficium within a new trilogy of forthcoming books entitled Triangulum Lamiarum (‘Triangle of the Witches’); no word yet on the other two titles.

Rather than being a single work, Veneficium is a collection of essays by Schulke, although it’s not clear what the provenance of all of them is. Two are from Michael Howard’s magazine The Cauldron, and one, between editions, was published in the Three Hands Press journal Clavis, while a previous version of another essay was submitted as an undergraduate paper. The rest, one assumes, are standalone pieces that were never intended to be published elsewhere. Despite this, there is a semblance of order, and, for example, the opening The Path Envenom’d (originally featured in The Cauldron #126) leads quite naturally into Purity, Contamination, & the Magical Virgin, with both sharing broad themes of venom and toxins, and the latter almost acting as the albedo to the melanosis of the former.

Veneficium succeeds best when it focuses not just on witchcraft in general but on some very particular and rather grimmer and grislier modalities. Thus, a piece like Leaves of Hekat, which broadly discusses the various noxious herbs used by Thessalian witches, is great and all, but it doesn’t compare to a trilogy which follows it, in which Schulke puts a microscope on three aspects of what one could call core witchcraft. Each of these essays addresses an element recorded in western European witchcraft trial accounts, revealing the rich symbolism and potential application behind what might otherwise be thought of as nothing but a scurrilous and salacious detail. In the first of these, The Spirit Meadow, Schulke considers the meadow, such as Basque field of Aquelarre, in which witches gathered for sabbats, identifying it as a locus rich in ecstatic power, capable of being visited via oneiric revelation and dream incubation. Beneath this idea of the meadow as a zone out of this world is a layer of agrarian symbolism that Schulke uses to identify it as a place of hidden poisons and monstrosity. The meadow of the witches, thus, provides a way of exploring various species of plants that could be found in its mundane counterpart, plants such as more noxious forms of wheat, and most famously, the wheat parasite ergot. A piece like this is effective because of the way in which the description of the field and its noxious constituents builds the image in question within the reader’s mind, just as would be necessary for anyone seeking to visit it in their mind’s eye.

The Spirit Meadow with its botanical curiosities gives way to The Matter of Man, where the poisons are the very components of the body and the magic in question is the corpse kind. Here, Schulke focuses on the idea of mumia, which, in addition to referring to the black resinous exudate scraped from embalmed Egyptian mummies to be used as a cure-all, is also employed, in the case of Sabbatic Witchcraft, as a term for sacrificial offerings derived from one’s own corporeality. The protoplasmic themes of The Matter of Man bleed (how apropos) into the next essay, The Witches’ Supper, in which Schulke unpacks the ideas behind the symbolism of sabbatic cannibalism and consumption, and includes a rather delightful list of nine poisons derived largely from putrefaction (so many potential death metal band names and album titles).

Throughout Veneficium, Schulke writes with the surety of one with a tradition behind him, ornamenting his language with archaic flourishes and expertly phrasing sentences in an often more complicated manner than is necessary. After all, why say “drinking it” when you can say “the act of its imbibition.”

In all, as it was in its first edition, Veneficium makes for an interesting read, even if the nature of the anthological format means there’s sometimes a little bleed between essays, with repetition resulting when ideas or concepts from an earlier essay are introduced anew. The combination of fundamentally interesting topics, especially when things get all messy and corporeal, and Schulke’s authoritative voice creates a valuable addition to the library. It is all very theoretical though, and despite Schulke’s occasional experiential anecdote, there’s not much in the way of suggestions about what to do with all these poisons. This is especially true when much time is spent pointing out the unremitting virulence of some of them, and there doesn’t seem much practical application to gangrenous amputation or multiple organ failure.

The cover of this edition of Veneficium features a reprise of a stunning painting by Benjamin A. Vierling, Sacred Heart, which depicts various inhabitants of the poisonous garden growing from the ventricles of a ruddy heart. Vierling also contributes a skull-festooned title plate and ornamental elements, while layout is by Joseph Uccello, who expertly employs a clean, clear style with the body set in a compact serif face that borders on the slab variety; don’t know what’s going on with the reverse indents in the footnotes, though, or the way some of them abruptly extend across two pages when other lengthier ones don’t. And speaking of the footnotes, there’s some inconsistency with how references are treated in them, with some essays citing title, author and page number, and others, despite clearly referencing a particular passage in a text, only giving the author and title.

Veneficium has been produced in three editions: standard, hardcover and deluxe. The standard edition, limited to 2,200 copes, is a trade paperback of 192 pages with a four page colour insert, while the 750 copy hardcover edition includes a dust jacket. The 50 exemplar deluxe edition is quarter-bound in purple goatskin, with special endpapers and a gilt-stamped slipcase.

Published by Three Hands Press