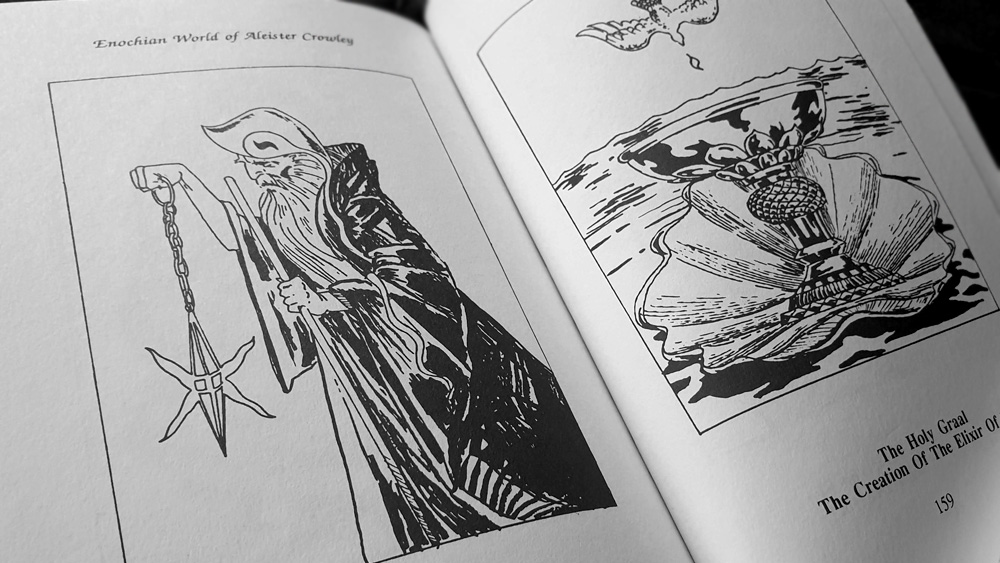

Enochian World of Aleister Crowley: Enochian Sex Magick is a seemingly ubiquitous title whose various editions are perpetually available through online book sellers. Principally written by Lon Milo DuQuette, the author credit for Crowley is due to the inclusion of Liber LXXXIV vel Chanokh from Volume I numbers VII and VIII of his Equinox periodical. This is reprinted in its entirety, images and all, with even the original plate numbering included. Lon Milo DuQuette is described on Wikipedia as being “best known as an author who applies humor in the field of Western Hermeticism” which explains the occasional attempts at badinage that one supposes is meant to be funny but which fall flat. This would suggest that comedy in occultism is in a pretty dire state, with nothing rising above the quip-heavy stylings that are characteristic of an uncle desperate for a laugh at a family gathering. The result is the appearance of humour but with none of the laughs; little aberrations that appear unbidden amongst otherwise conventional discussions, made all the more incongruous by their failure to land.

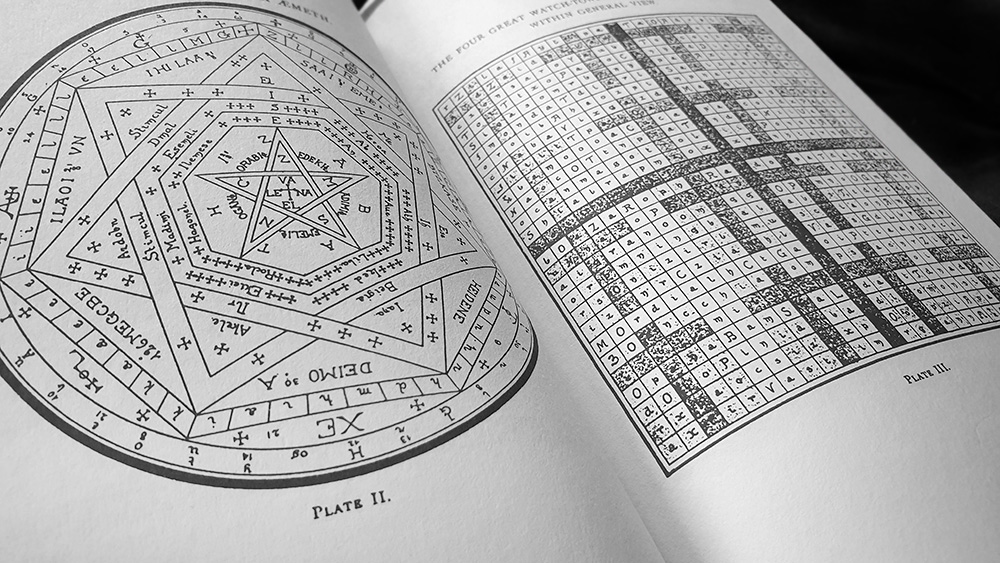

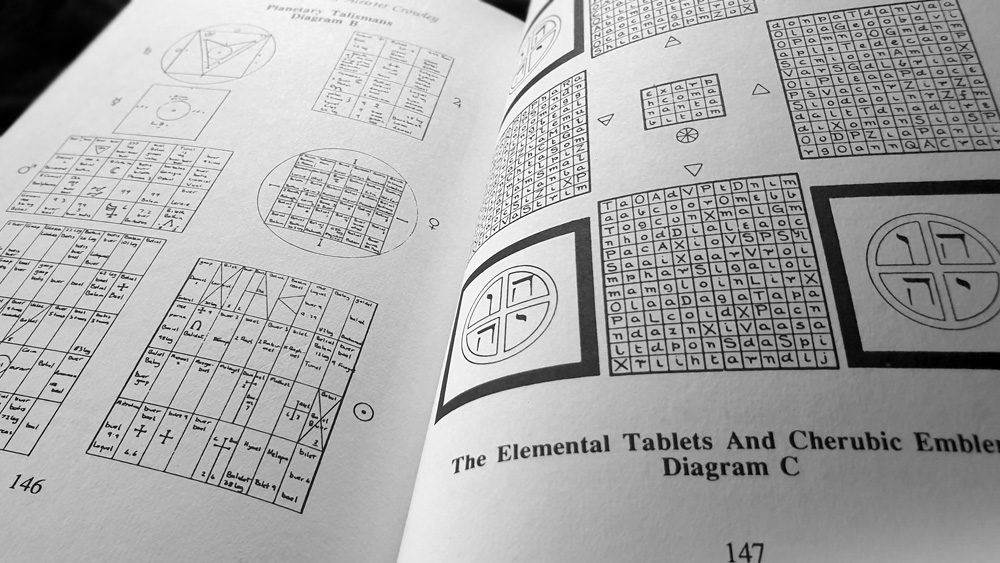

Enochian World of Aleister Crowley: Enochian Sex Magick is a seemingly ubiquitous title whose various editions are perpetually available through online book sellers. Principally written by Lon Milo DuQuette, the author credit for Crowley is due to the inclusion of Liber LXXXIV vel Chanokh from Volume I numbers VII and VIII of his Equinox periodical. This is reprinted in its entirety, images and all, with even the original plate numbering included. Lon Milo DuQuette is described on Wikipedia as being “best known as an author who applies humor in the field of Western Hermeticism” which explains the occasional attempts at badinage that one supposes is meant to be funny but which fall flat. This would suggest that comedy in occultism is in a pretty dire state, with nothing rising above the quip-heavy stylings that are characteristic of an uncle desperate for a laugh at a family gathering. The result is the appearance of humour but with none of the laughs; little aberrations that appear unbidden amongst otherwise conventional discussions, made all the more incongruous by their failure to land.

Without the inclusion of Liber LXXXIV vel Chanokh there wouldn’t be much to this book as it is effectively a reprint of that liber with DuQuette providing a preamble that he refers to as a ten minute overview, introducing the text and trying to simplify it with some added context. The sex magick promised in the book’s title is not incorporated into this early section, nor is it obviously in the reprint of Liber LXXXIV, but is instead tacked on at the end. First there’s an ever-so-brief chapter from DuQuette titled Divine Eroticism which introduces the idea of intimate relations betwixt the human and divine, and this is then followed by Christopher S. Hyatt’s Techniques of Enochian Sex Magick.

Finally, one might think, here we go, but you’d better tell that thought to slow down and stop rubbing its neural hands together because there’s not much here, and certainly little that is explicitly Enochian in the sex part. Instead, Hyatt presents a way to explore the Enochian aethyrs by doing the de rigueur Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram, reciting the Call of the 30th Aethyr and vibrating the names of the governors of the respective aethyr. With that done, you try and forget all about it by taking a sex break, and use the heightened state following climax to better visualise the imagined journey through the intended aethyr. There’s another procedure included here, a creation of a magickal child, but again, the Enochiana feels largely tacked on in a manner that anyone could have come up with. Despite the relative brevity of the book, this disappointing conclusion makes the journey through the preceding 108 pages feels so much longer; all this plodding through half-jokes and a reprint of someone else’s work for that?

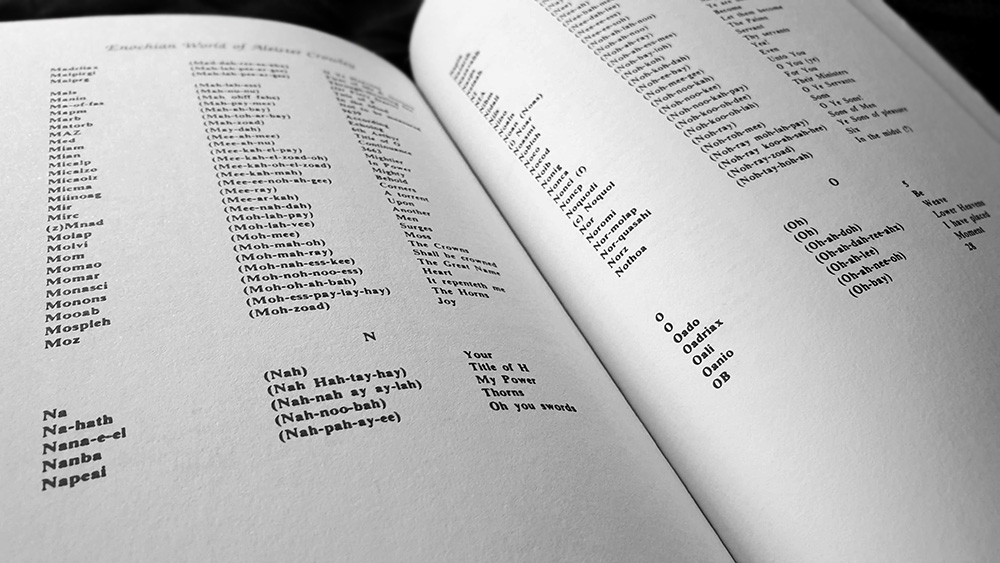

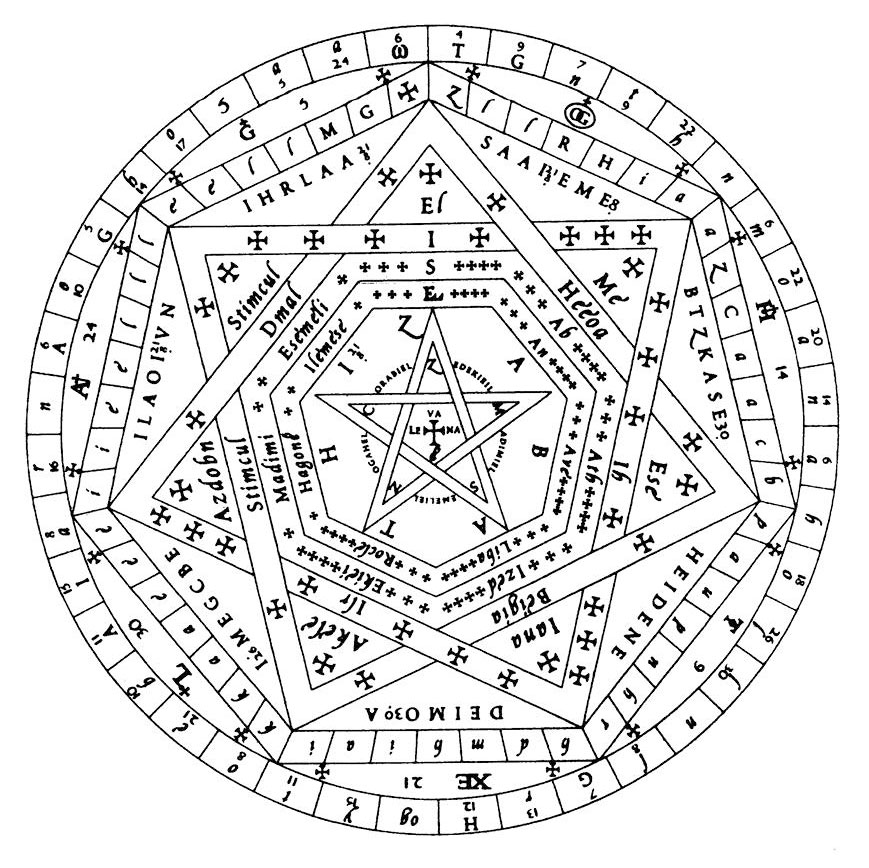

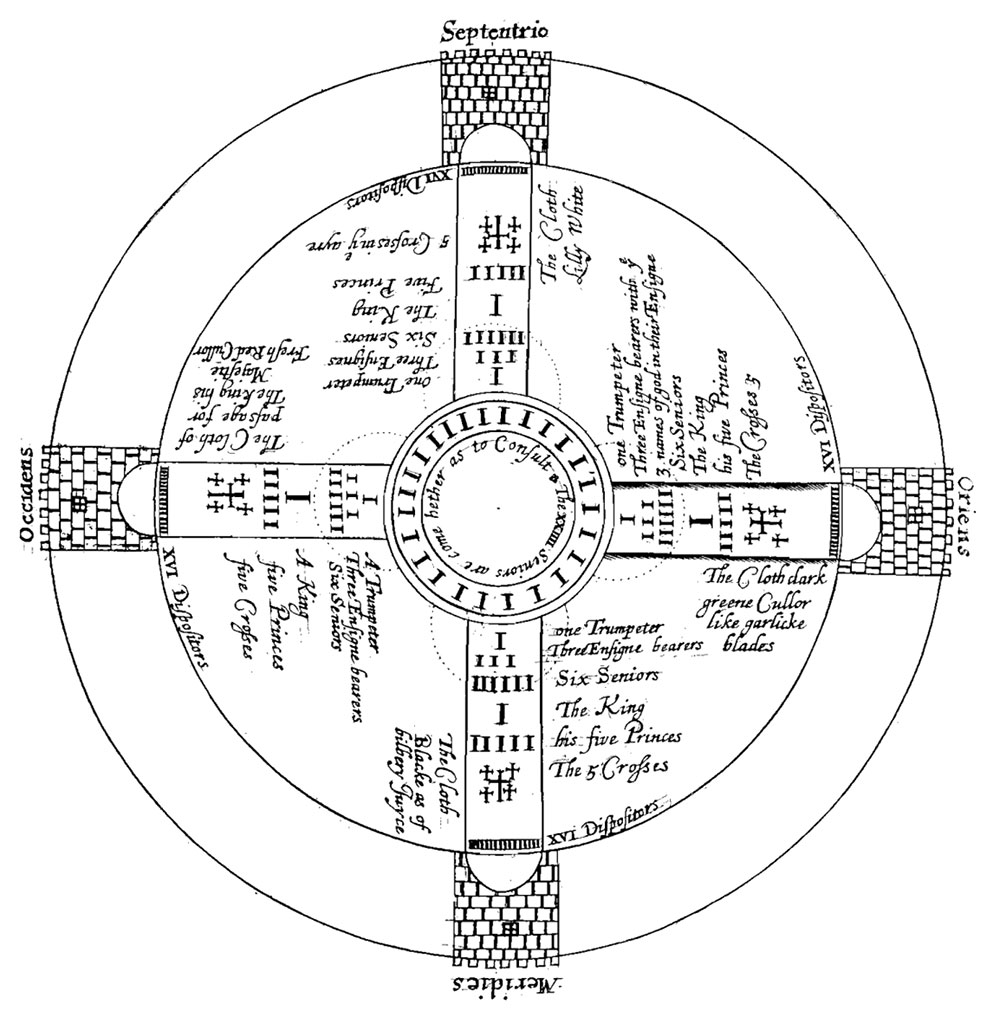

Enochian World of Aleister Crowley: Enochian Sex Magick concludes with more reprints, beginning with Israel Regardie’s Enochian dictionary (boosting the page count by 18, which is far more than Hyatt’s sex magick contributions), followed by Crowley’s Lesser Ritual of the Hexagram because at this point, sure, why not? Then there’s an appendix of the various Enochian ritual diagrams such as the elemental tablets and the tablet of union, but also a hand-drawn reproduction of the Seven Ensigns of Creation that is rendered so small as to be unreadable, making its inclusion entirely useless. Oh, and just for good measure, two pages are spent on reprints of the diagrams of the body postures used in the Golden Dawn’s operations: the neophyte signs, the signs of elemental grades, and the four L.U.X. signs, because anything will do to push that page count.

There is one final padding of the page count at the end of the book which is referred to grandly as Sex Magick Symbols. But this merely consists of eight full-page illustrations crudely rendered in something resembling the style of ballpoint pen heavy metal doodles on a teenager’s exercise book. The creator of these images has illustrator credits in two other repeatedly-republished New Falcon titles, so well done, I suppose.

The copy of the book reviewed here from 2006 inconceivably represented its sixth printing since 1991, and there have been, for reasons unexplained, even more pressings since then. The covers of some earlier editions are sans both the promise of “Enochian Sex Magic” in the title, and the credit to Christopher S. Hyatt, despite the content being there, while a 2021 edition employs a new twist on the title with the awkward Enochian Sex Magic and How to Workbook which also bears a promise of “Brand New Material by Lon Milo DuQuette.” With the slight nature of this volume, and given that so much of those pages are the reprint of Crowley’s Liber LXXXIV vel Chanokh and DuQuette’s preamble describing what is in Chanokh, it is hard to understand what warranted this constant reprinting, other than an ongoing income stream due to its low effort and low overheads.

Enochian World of Aleister Crowley: Enochian Sex Magick runs to a mere 162 pages, with a large chunk of this being the reprint of Liber LXXXIV vel Chanokh and its related ephemera. As with seemingly all New Falcon titles, the presentation is ugly and graceless with formatting that is all over the place. Typesetting choices reflect the aesthetics of entry-level desktop publishing of decades ago, with little hierarchy or sense of élan or care. Almost everything is formatted in Times New Roman set at a point size that is too large, accompanied by equally generous indents that are permanently set to ‘on,’ irrespective of the paragraph type or the contents. The only typographic contrast is provided by a cheap cursive that is used for chapter headings, while block quotes are frustratingly rendered in a bold italic type whose heavy weight and the superfluous space from excessive leading and full justification conflicts with its markedly smaller point size. Typographic chaos abounds due to the surfeit of short sentences with the far too severe idents, further compounded by some of them featuring numbers but not being formatted as numbered lists. Such clutter. This carelessness is particularly evident in the typesetting of something as complicated to format as Liber LXXXIV vel Chanokh, especially when it is contrasted with the effortless class and refinement of the text’s original rendering in Equinox.

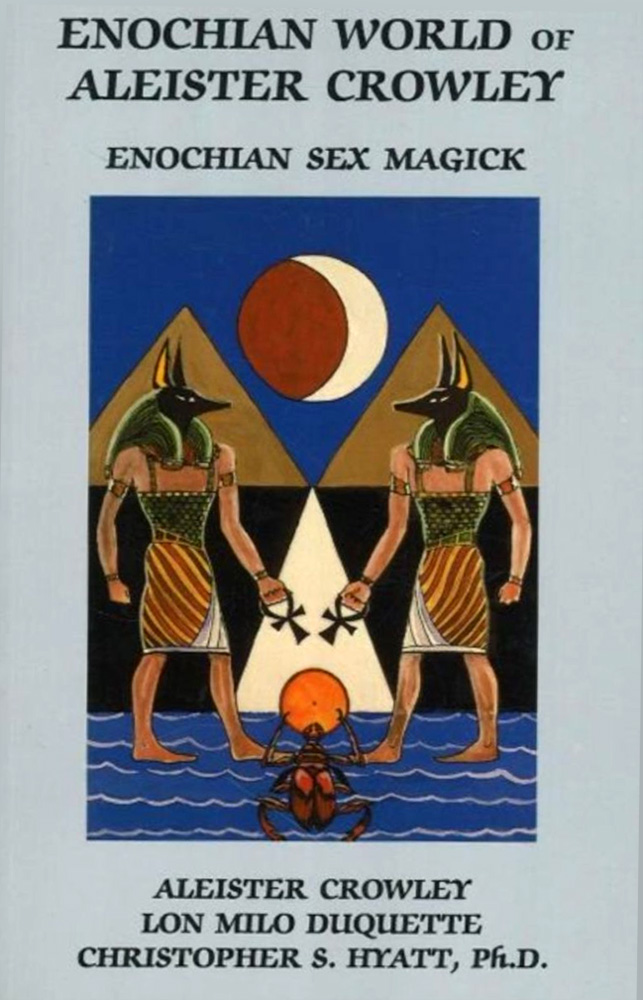

The cover art for the printing reviewed here, and in some of the other early editions, uses an inexplicable painting of an Egyptian scene with twinned ankh-wielding Anubis in front of a moon, rather than anything remotely Enochian. This painting is credited to S. Jason Black, who is described on the Falcon Press website as a “professional psychic, much sought after for his accuracy…” neat, though they are apparently less concerned with being accurate when it comes to creating Enochian cover art in which wild Anubi appear. Other editions have used various images of Crowley or Enochiania as the cover art, one and supposes that we should be just grateful that some of them haven’t taken the sex magick theme and ran with that.

Published by New Falcon Publications