Magic in the Modern World is another entry in Penn State Press’ ever reliable Magic in History series and brings together eight essays with contributions from Egil Asprem, Erik Davis, Megan Goodwin, Dan Harms, Adam Jortner, and Benedek Láng, as well as editors Edward Bever and Randall Styers. Beyers and Styers divide the contents into two sections, beginning with Magic and the Making of Modernity, which could be broadly said to reflect a foundational theoretical approach with broad strokes outlying the interactions between magic and modernity. This leaves the second half, Magic in Modernity, to explore some fun case studies with more of a focus on the idea of legitimisation in magical practice.

Magic in the Modern World is another entry in Penn State Press’ ever reliable Magic in History series and brings together eight essays with contributions from Egil Asprem, Erik Davis, Megan Goodwin, Dan Harms, Adam Jortner, and Benedek Láng, as well as editors Edward Bever and Randall Styers. Beyers and Styers divide the contents into two sections, beginning with Magic and the Making of Modernity, which could be broadly said to reflect a foundational theoretical approach with broad strokes outlying the interactions between magic and modernity. This leaves the second half, Magic in Modernity, to explore some fun case studies with more of a focus on the idea of legitimisation in magical practice.

One of the two core themes of this collection is how modernity has been defined in explicit opposition to magic and superstition, but with a counterargument that sometimes the role of disenchantment in the modern world has been greatly overstated, and as a result, much like the perennial punk battle cry, magic’s not dead. Styers set the stage to this in the opening Bad Habits, or, How Superstition Disappeared in the Modern World, documenting how superstition was increasingly framed in psychological terms through the various stages of modernity until it attained the status of a delusion that was an inherent threat to the order of society.

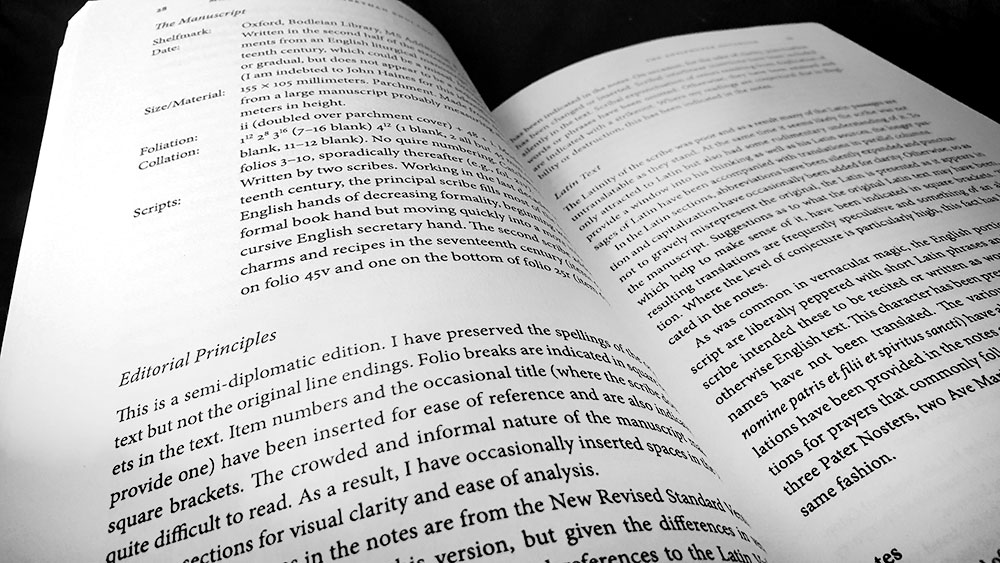

As in another reviewed title from Penn State Press, Frank Klaassen’s Making Magic in Elizabethan England, Max Weber’s concept of Entzauberung and its assumed totality is swiftly undone. In Descartes’ Dreams, the Neuropsychology of Disbelief, and the Making of the Modern Self, Bever discusses the three pivotal dreams that René Descartes experienced on a November night in 1619, and thereafter believed that a divine spirit had revealed to him a new philosophy. That Cartesian thought, that most rational of philosophies, emerged from an irrational, spiritual event, underscores how the rational cannot be so easily separated from the mystical.

For his contribution Benedek Láng explains, in the words of the title, Why Magic Cannot Be Falsified by Experiments, beginning with a question as to why scribes and collectors of grimoire did not see that some of the more ridiculous spells and operations couldn’t possibly work, whether it’s becoming invisible with certain herbs, or expelling all scorpions from Baghdad. Ultimately, Láng’s essay is a questioning of the whole idea of crucial experiments, be they in matters magical or the science laboratory.

The final essay categorised as Magic and the Making of Modernity is Adam Jortner’s Witches as Liars, which looks at the relationship between witchcraft and civilization in the Early American Republic. He argues that the rationalist response to concepts of magic and witchcraft was fundamental in the development of the political and social structures of the Jeffersonian and Jacksonian United States, with the irrationality of magic being seen not only as antithetical but as a direct threat to the nascent order of social democracy.

The four entries gathered under the heading of Magic in Modernity are a diverse bunch, covering off Enochian magic, Jack Parsons and rocketry, Seidr in contemporary Norse paganism, and Simon’s Necronomicon. That’s truly something for everyone, and Egil Asprem starts things off with Loagaeth, Q Consibra A Caosg, which navigates what he defines as the contested arena of modern Enochian angel magic. He provides a potted history of Dee and Kelley’s Enochian revelations, showing how the magical system broadly fits within Dee’s version of natural philosophy, before breaking down how these foundations have been built upon and interpreted by subsequent practitioners, ultimately taking the material far from its roots. This is familiar territory for Asprem, having written the previously reviewed Arguing With Angels, which pursued similar concerns, but with a considerably higher page count. For this outing, Enochian magic makes a suitable area for considerations of legitimisation, not just because of the inherently suspect origin of the system (transmitted by angels to a known forger in Edward Kelley) but because of the way in which subsequent adoption of its elements (or a veneer thereof) have required mental gymnastics to justify their diversions from the source.

In Babalon Launching: Jack Parsons, Rocketry, and the ‘Method of Science,’ Erik Davis considers the intersection between Parsons’s magical work and his career in rocketry, two worlds he largely kept separate. This an enjoyable read, with Davis effectively giving a brief overview of Parson’s life, focussing on particular moments and showing how the scientific model interacted with the magical one. Parsons becomes an example of how romance and rationalism are not compartmentalised or balanced in occultism, with Davis arguing that modern occultism, specifically its Thelemic strands, does not simply seek to re-enchant the world but is instead an aggressive performance of pluralism with a structural ambiguity founded on deconstructed notions of belief.

Megan Goodwin enters the world of contemporary Norse paganism with Manning the High Seat, exploring how the magical technique of Seidr is used and how its implicit associations with gender and sexuality are navigated by male practitioners. Goodwin presents a brief historical overview of Seidr before exploring the perspectives of two people, Jenny Blain and Raven Kaldera. Blain’s significant role in the promotion of Seidr in Norse Neopaganism ensures her presence here, with Goodwin crediting her with making an important contribution to the scholarship or gender and magic, and providing a thorough review of her understanding of Seidr, particularly its relation to sexuality. As Goodwin notes, though, Blain’s perspective never moves beyond the binary, employing rather basic dichotomies of straight and gay, male and female, and with none of the queer ambiguity and multiplicity that is implicit in the definition of Seidr as ergi. The ergi is plentiful in Kaldera’s definition of Seidr, though, and Goodwin appears to have a lot of sympathy for him in the presentation of his approach.

In the final essay, Dan Harms is well ensconced in his Lovecraftian wheelhouse with a consideration of the strategies of legitimisation used in the presentation of the trade paperback version of the Necronomicon by the mononymic Simon. There’s probably no other work in occult publishing that has a greater need for legitimisation than Simon’s Necronomicon, not just because it purports to be the non-fiction version of a fictional book, but because it always had an air of inauthenticity about it, right down to the cliché origin story with the mysterious monk revealing the manuscript before disappearing into unverifiable oblivion. It also seemed to be such a product of the occult scene of the 1970s New York, especially with how Herman Slater’s Warlock Shoppe was so central to its mythos, along with all those familiar scene names. Despite the transparency of the deception, Harms doesn’t descend into invective or scorn (as he is sometimes wont to do when discussing such matter on his more informal blog), but rather presents a considered analysis of each of the strategies used by Simon within the book and in marketing. There are a couple of classic strats here, as one would expect, with the most obvious being appeals to authority through comparisons to a bricolage of religious and mystical traditions, employing reduction to simplify these and enable pattern recognition to an uninformed audience.

In all, Magic in the Modern World is an interesting read, particularly in the second half where the four entries all offer something different. Body copy is devoid of any illustrations with the text set in Minion Pro by Coghill Composition Company, and presented in the consistent Magic in History style.

Published by the Pennsylvania State University Press