Back when Scriptus Recensera launched, the Word document that forms the master copy of the reviews here (and which now runs to 110 pages) had a provisional list of headings, with the names of books to review. It still works like that, new review-worthy titles are added when they arrive and quickly, or eventually, the space beneath them is filled in as they are rapidly, or slowly, read. One title that has been there resolutely from the beginning, seeing its companions reviewed and sent down the pages of the file, is Scarlet Imprint’s Howlings, so let’s for lots of reasons I’m sure, and not just to finally put it to rest, review it exactly ten years after its release.

Back when Scriptus Recensera launched, the Word document that forms the master copy of the reviews here (and which now runs to 110 pages) had a provisional list of headings, with the names of books to review. It still works like that, new review-worthy titles are added when they arrive and quickly, or eventually, the space beneath them is filled in as they are rapidly, or slowly, read. One title that has been there resolutely from the beginning, seeing its companions reviewed and sent down the pages of the file, is Scarlet Imprint’s Howlings, so let’s for lots of reasons I’m sure, and not just to finally put it to rest, review it exactly ten years after its release.

Howlings was Scarlet Imprint’s first anthology concerning grimoire-related writings, and it was later followed by the previously reviewed Diabolical. It bears the perfect name for such a title, seemingly ambiguous and modern (like some noise-rock duo… *pause for searching* well, what do you know, it’s a witch house producer from California), but referring appropriately to a seemingly contentious translation of goetia as ‘howling.’ The Goetia is just one of the grimoires explored by the multiplicious howling voices in the fourteen essays that make up the singular Howlings, along with The Picatrix, Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Michael Bertiaux’s The Voudon Gnostic Workbook, Aleister Crowley’s Liber 231, and Andrew Chumbley’s Qutub.

Fittingly, it is The Goetia that receives the most attention in Howlings, with a total of six essays addressing various aspects of the 17th century grimoire, featuring contributions from Paul Hughes-Barlow, Aleq Grai, David Rankine (who also later contributes a piece on Agrippa and magical squares), Peter Grey, and two from Thea Faye. In the first of her two pieces, Sex in the Circle, Faye considers aspects of gender in invocation, while in the second, and continuing with her largely practical approach, she addresses the trustworthiness of the various goetic spirits. Considering that in The Goetia there are 72 spirits available to practitioners, it’s interesting that one of them, Andromalius, finder of thieves and treasure, receives somewhat disproportionate attention here, being the focus of Hughes-Barlow’s piece, and also featuring heavily in Aleq Grai’s Tools of the Goetia, which includes a transcript of a ritual conversation with them.

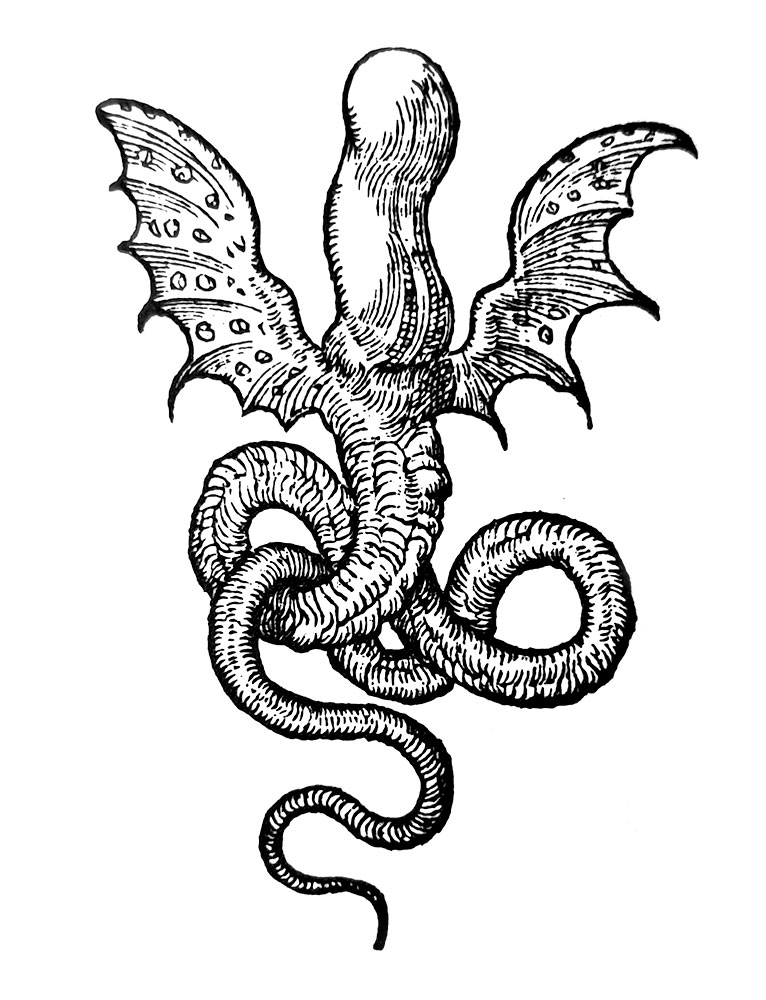

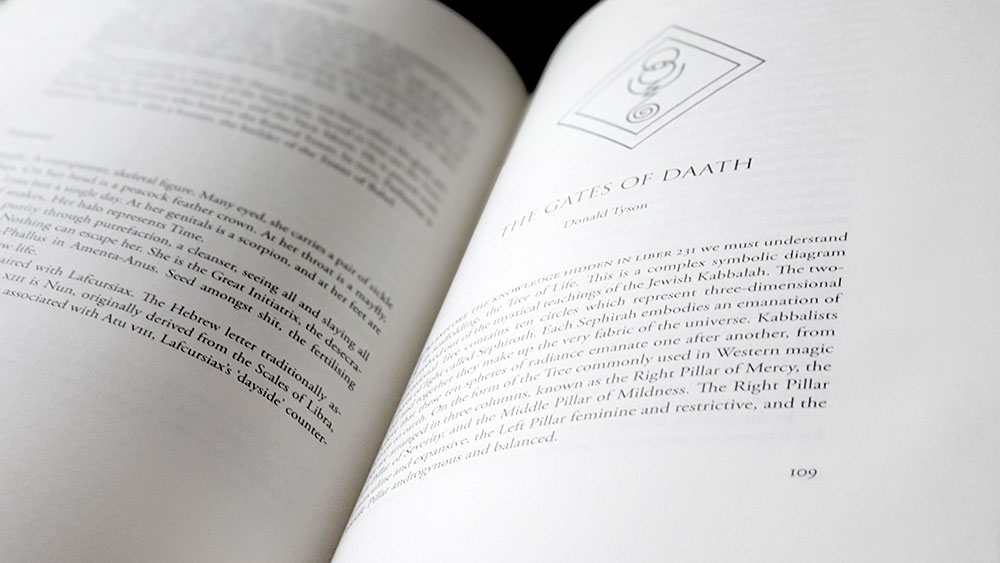

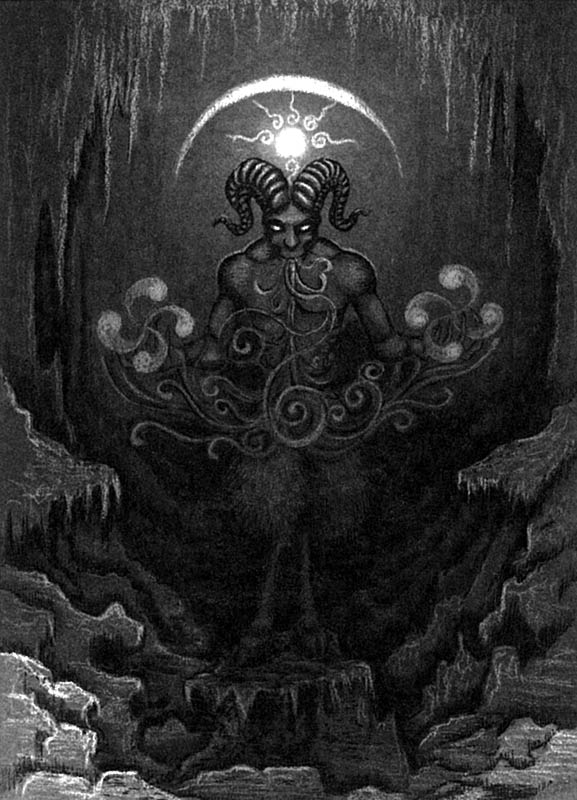

For those with more caliginous inclinations, Crowley’s qliphothic text Liber 231 receives attention from Krzysztof Azarewicz, Stafford Stone and Donald Tyson. Azarewicz broadly considers the text itself, while Tyson’s 49 page The Gates of Daath, the longest contribution in this anthology, is a wide-ranging consideration of sephiroth, qliphoth and their tarot attributions, particularly in regard, as one would expect, to the nullsphere of Daath. As he would later do in Diabolical, Stafford Stone’s contribution to things nightside are a selection of cards from his Nightside Tarot (Baratchial, Gargophias, Uriens and Niantiel), accompanied by brief battlefield notes, as he calls them, describing each of the featured atu and their perpetually symmetrical spirits.

One of the things that appeals about Howlings, and it is summed up in the subtitle to David Beth’s Bertiaux-themed Into the Meon essay, Approaching the Voudon Gnostic Workbook, is that feeling of a supremely personal interaction with the writer’s grimoire of choice. Where Howlings succeeds most is in those instances where the idea is one of encountering, exploring and experiencing a tome; something that appeals to the bibliophile in me. While writing should be rigorous without doubt, those qualities are enhanced here by the enthusiasm of the contributors, where the interaction with the grimoire is experiential, visceral and profound. At the same time, though, this approach doesn’t always work, and some of the essays reflecting on the author’s personal journey wither in comparison to those with more of an academic skill set. The latter succeeds is in those instances where the personal is combined with a clear, authoritative voice, and with stellar writing skills; something not always the case with so many contributors.

Scarlet Imprint’s Peter Grey fulfils the promise that a volume such as this offers with his perfectly titled The Stifling Air. Combining the personal with historical antecedents, Grey writes in a beautifully poetic manner that engages with its tone but doesn’t get too purple in its prose. His is a picturesque tribute to the ritual virtues of smoke and incense, beginning with a panegyric overview before considering various incenses individually and extensively. That sense of personal interaction is also evident in Jack Macbeth’s Getting to the Point, which acts as both paean and practicum for Chumbley’s poetic text Qutub. Macbeth writes affectionately of Chumbley’s relatively brief work, describing it as hypnotic, whirling and a “many layered exposition on the sorcerous arte.”

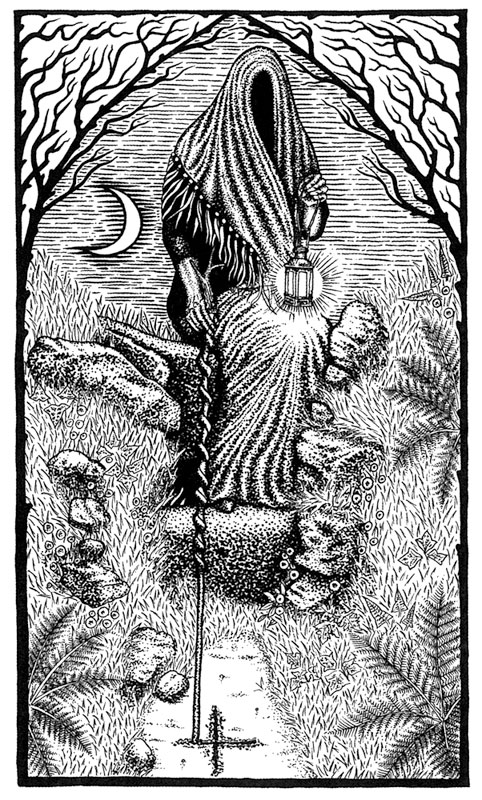

The formatting in Howlings is as lovely as one would expect from Scarlet Imprint, with type set at a small but readable serif face, framed by large margins and a generous footer. Given the multitude of contributors, there’s understandably variance in how images are presented, with sigils rendered differently in weight and style, but otherwise the quality is fine. The one exception is in the reproduction of two engravings by Albrecht Dürer, with Melancholia not as a sharp as it could be, while The Angle with the Key to the Bottomless Pit is unforgivably and surprisingly soft, murky and blurry.

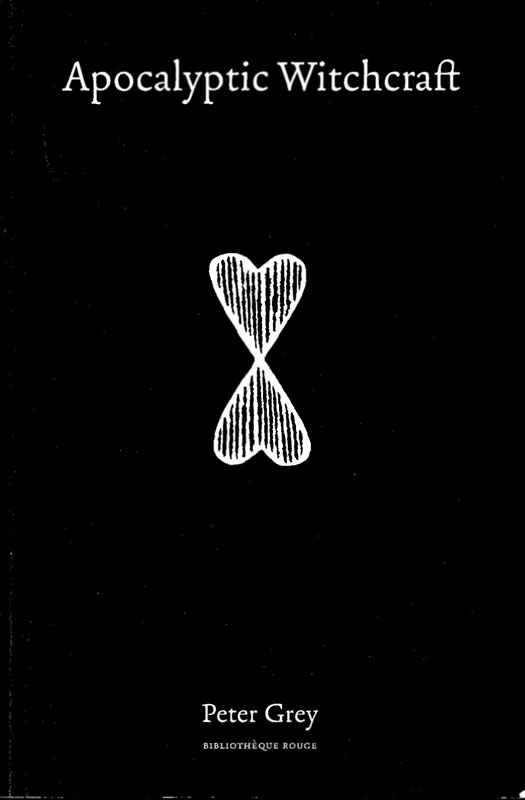

Howlings was released in several editions, with the first being a limited and hand-numbered edition of 333 copies. The second edition consists of 666 copies but is confusingly numbered sequentially from 334 to 999, of which this reviewer’s copy (for those keeping score at home) is number 782. It has black endpapers, black and white illustrations, colour plates and is bound in turquoise cloth, with gilt titling to spine and an geometric Islamic design foiled over the entire front. Although, as with other Scarlet Imprint titles, this foiling has, with the passage of time, flaked and faded in places, despite the impeccable archival standards at Scriptus Recensera. Contact with the cover through the mere act of reading means that by the time you finish the book, the cover will have changed, appearing worn in those places where your hands have rested. Feature or a bug, you decide.

Published by Scarlet Imprint