Adorned with a gold-foiled version of a symbol representing Mictlantecutli, the Aztec god of death, Underworld resembles in length and dimensions another recently reviewed title from Theion Publishing, The Cult of the Black Cube. And, just as that book was credited to the pseudonymous Dr Arthur Moros, this volume is presented somewhat anonymously as the work of the infuriatingly-spelt Sepulcher Society, an organisation for which precious little information can be found; and, after fruitless Googling, I’m almost certain they’re not the Sepulchre Society of Sussex in M.J. Trow’s novel Maxwell’s Grave… or are they? Dun dun dunnn.

Adorned with a gold-foiled version of a symbol representing Mictlantecutli, the Aztec god of death, Underworld resembles in length and dimensions another recently reviewed title from Theion Publishing, The Cult of the Black Cube. And, just as that book was credited to the pseudonymous Dr Arthur Moros, this volume is presented somewhat anonymously as the work of the infuriatingly-spelt Sepulcher Society, an organisation for which precious little information can be found; and, after fruitless Googling, I’m almost certain they’re not the Sepulchre Society of Sussex in M.J. Trow’s novel Maxwell’s Grave… or are they? Dun dun dunnn.

Where The Cult of the Black Cube dealt with various incarnations of the Saturnine deity, Underworld, as its title suggests, considers the subterranean world of the dead, following a similar approach to Moros’ book by exploring examples of the theme from a variety of cultures, consolidating the wisdom so gleaned, and then throwing in a few bits of practical work. Like Moros, the pseudonymous author (who uses a singular first person ‘I’ despite the credit to the presumably multiple-membered society) provides something of a personal touch, opening with a brief biography that stretches back to their childhood and encounters there with death and general spookiness.

Underworld is divided into just three chapters, but these would be more fittingly described as parts, each being lengthy and consisting of smaller chapter-like sections, rather than a straight forward narrative, all divided up with the appropriate formatting. In the first, the author, as we must pseudonymously call them lest we henceforth laboriously refer to them as the Sepulcher Society, gives a survey of various examples of the underworld, with summaries running to up to five or six pages of the Babylonian, Greek and Roman, Celtic, Germanic, Aztec, and Hindu conceptions of the underworld. These are all as thorough as one can be with the amount of space afforded, although, as with the rest of the book, there’s very little in the way of referencing, be it in-body citations or footnoted sources. Given the specialised nature of the discussion here, in particular Aztec and Babylonian conceptions of the underworld, it is frustrating having no sense of the source of the information, and no indication as to whether it’s from primary texts or secondary academic discussions or synopsises. There are occasionally footnoted references to suggested further reading on particular areas of consideration, as well as a bibliography at the rear of the book, but there is never any indication that these titles are necessarily the source, and there’s certainly no direct referencing to specific pages within them.

Having described the mythological precedents of the underworld, the author concludes the first chapter with a synthesis of common chthonian elements, highlighting those geographical features found in many accounts, irrespective of distances in space or time: a twilight realm between the living and the dead, a barrier of dark water be it river or sea, the black gates that guard the underworld, and finally, the underworld itself, its city and its inhabitants, ruled by a dark queen and a black king.

The second chapter turns to the gods of the underworld themselves and begins with the author establishing several working hypotheses, principally that the gods are real beings with agency of their own, not simply aspects of one’s unconscious, or even archetypes or thought-forms made manifest by the collective members of a society. The author does provide something of a syncretistic angle, though, suggesting that one’s cultural context may create the lens through which the same deity may be viewed differently, adopting a name, characteristics and appearances that draw from the prevailing cosmology. This belief in the very literal existence of the gods, indeed all gods, does go down some rather specious rabbit holes, such as suggesting that Jews, Muslims and Christians must all worship different deities since clearly tension betwixt the three religions is the result of three different deities battling each other for control. An intriguing proposal, but an alternate hypothesis might be: people are dicks. Similarly, the author suggests that the growth and subsequent power of a religion is indicative of the respective deity’s standing in ye olde god stakes, but once again, let’s proffer the more circumspect suggestion that, yes, as previously mentioned, people are dicks, and the growth of a religion is often demonstrably due to said people being said dicks and making that happen because it is in their best dickish interests to do so.

With the theory out of the way, the author returns with a greater focus to the gods whose realms were discussed in the first chapter. Referring to these gods as chthonians, the author begins in Mexico, initially exploring the godforms of Mictecacihuatl and her partner Mictlantecutli, the Aztec goddess and god of death and the underworld. This gives way to two figures that, it could be argued, are their contemporary embodiments or descendants, the Mexican saint of death Santa Muerte, and her male equivalent from further south in the Americas, San La Muerte. Given the well-documented nature of Santa Muerte’s cult and praxis, the author is well equipped to provide an extensive, multi-paged section on practical devotion towards her, both summarising her place in Mexican folk magic, and ending with a few ritual suggestions and a little liturgy. The same cannot be said for San La Muerte whose relative obscurity in comparison to his popular Mexican sister is reflected in the paucity of information presented here.

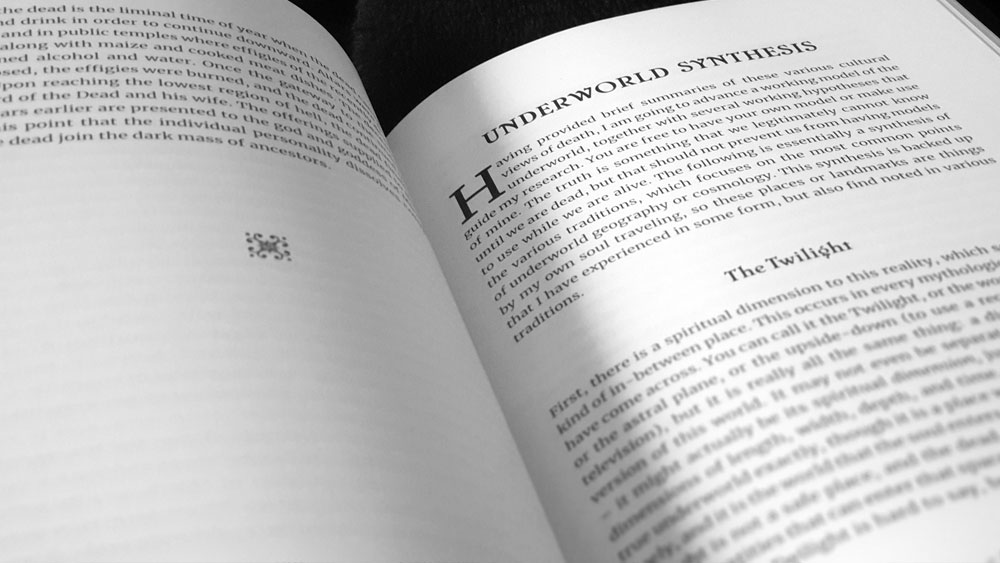

The other mythological systems covered here don’t provide the same luxury in terms of contemporary usage as Santa Muerte, but the author does try their damnedest to fill those gaps. They turn to Babylon next, discussing Erishkigal and then Nergal, with descriptions of each godform and suggestions for contemporary ritual or devotional techniques, before a similar exploration of the natal demoness Lamashtu. The same then follows for cultures Germanic (Hela), Greco-Roman (Nyx, Pluto, Persephone), Celtic (the Morrighan), and Indian (Yama, Varahi). Each deity is given a brief description or background, a summary of how they are or can be worshipped now, followed by descriptions of shrines, offerings and images, and an example of a ritual. These are not techniques cut and pasted with the respective gods swapped out, but there are certain recurrent themes of practice here, principally the development of devotional altar space or effigies, a pretty fail-safe approach to dealing with deities.

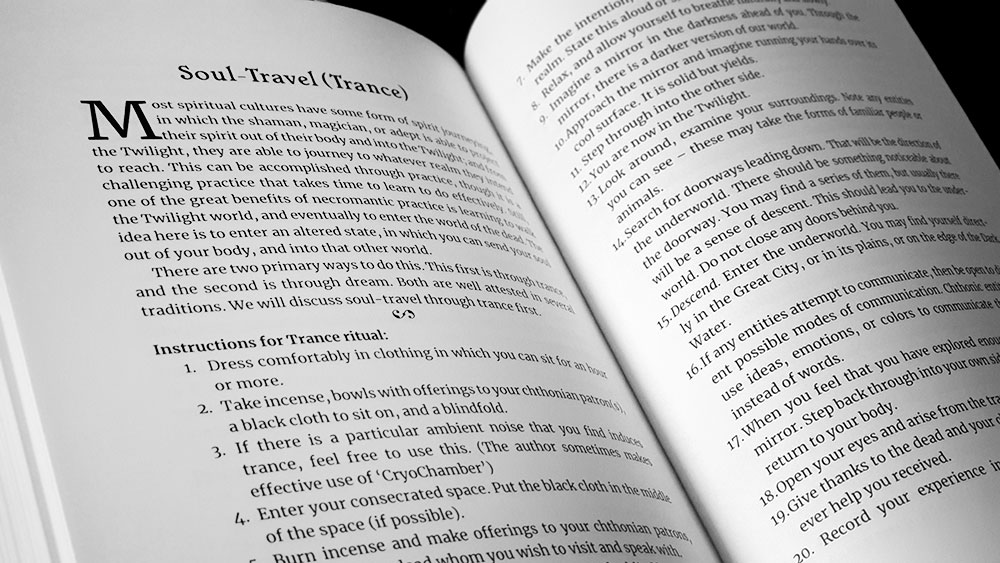

Underworld concludes with its third chapter, Necromancy, where the author puts the dead to work, defining necromancy not just as the raising of the dead for mantic purposes, but any magic that deals with death and the underworld’s entities and energies. This builds on the syncretism and basic ritualism touched on in earlier pages, incorporating from a practical perspective the use of ritual and devotional space, and then providing techniques for travelling in trance and dream, and communicating with the dead. These are presented as broad guidelines that can be built upon by the practitioner, and while they don’t cover much in the way of new occult ground (what does?), the instructions are clear and consistent.

Underworld comes in two editions, a standard cloth hardcover, and the Auric Edition. The standard edition of 720 copies is bound in black fine cloth, with a design debossed and foiled in gold on the cover, with the same for lettering on spine. The sold out Auric Edition of 52 copies is fully hand-bound in chthonic dark-brown fine leather, with raised bands, embossing on spine, and a ribbon. The cover of each Auric copy carries an embedded specially manufactured brass obol coin as used by members of the Sepulcher Society to traffic with Hades. Each Auric copy also includes an exclusive additional page of fine paper, containing a ritual to awaken the Shadow Self for necromantic contact.

Published by Theion Publishing