Philip C. Almond is all about new biographies, having previously used that titular conceit for explorations of both God and the Devil. This latest biography acts as a companion to one of those, his 2014 work on the Devil, and like its predecessor, it is imminently readable with its body copy set in a larger-than-usual point size on smaller-than-usual digest-size pages (averaging ten words a line), all aided by Almond’s easy manner and authorial voice.

Philip C. Almond is all about new biographies, having previously used that titular conceit for explorations of both God and the Devil. This latest biography acts as a companion to one of those, his 2014 work on the Devil, and like its predecessor, it is imminently readable with its body copy set in a larger-than-usual point size on smaller-than-usual digest-size pages (averaging ten words a line), all aided by Almond’s easy manner and authorial voice.

Any consideration of the Antichrist inevitably brings to mind Bernard McGinn’s masterful exploration of the topic, 1994’s Anti-Christ: Two Thousand Years of the Human Fascination with Evil. Almond acknowledges a debt to McGinn for that work and his other many titles, mentioning the quote from Denis the Carthusian with which McGinn closed his own study, “Have we not worn ourselves out with that accursed Antichrist.” With the completion of this biography, Almond wryly notes that he now includes himself amongst the company of Denis and McGinn as a sufferer of this Antichrist-fatigue.

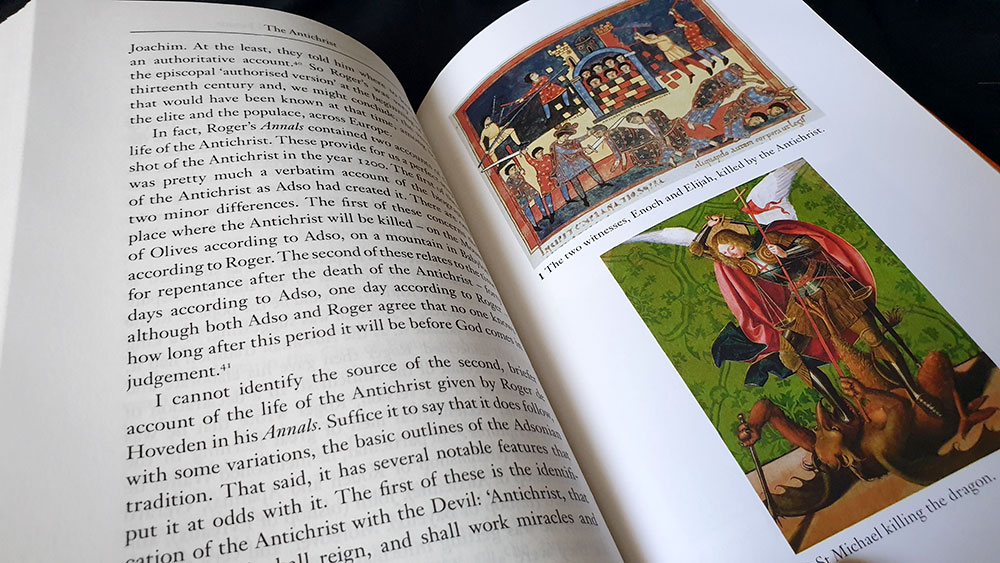

Almond opens by describing the Antichrist as a fluid and unstable idea from its inception, and noting how from this flux emerged two primary characterisations: the tyrannical Antichrist who opposes and persecutes the Christian church, followed by the later concept of a hypocritical papal Antichrist who deceives from within the very church. The former idea, which dominated the first millennium of the Common Era, was consolidated in its last century by Adso, a Benedictine monk from Montier-en-Der in north-eastern France. For his first chapter, Almond summarises Adso’s highly detailed biography of the Antichrist as a Jew born of the tribe of Dan, into whose mother the Devil would enter at the moment of conception so that the child, though conceived by human parents, would be “totally wicked, totally evil, totally lost.” Born in Babylon and raised in the unrepentant Galilean cities of Beth-saida and Corozain, the Antichrist would travel to Jerusalem where he would circumcise himself, upon which the Jews would flock to him as the Messiah. He would then terrorise Christians, and kill the returning Old Testament figures of Enoch and Elijah (sent by God to convert the Jews to Christianity), until after a three and a half year period of tribulations he would be defeated by either Jesus or the archangel Michael. With this narrative established by Adso, Almond, in a rather pleasing device, then takes a historical step backwards and shows how a millennium’s worth of influences and eschatological speculation culminated in its creation.

This analysis begins by exploring the considerably slight appearances of the Antichrist in the biblical record, the first of which is the plurality of lowercase antichrists that are mentioned in some of John’s epistles, where the term is used as a pejorative directed against fellow but estranged Christians who, contrary to orthodox interpretation, denied the divinity of Jesus. Almond then highlights less specific elements from both the Old and New testaments that would be incorporated into the vision of the singular Antichrist, beginning with the analogous false prophets and false messiahs which Jesus warns of in Mark’s gospel when discussing the end times. In the same gospel, Jesus also talks about the abomination of desolation or desolating sacrilege, an idea drawn from the Old Testament book of Daniel and the first book of the deuterocanonical Maccabees, where the term refers to the profanation of the temple in Jerusalem by a foreign tyrant (for Daniel, the second century BCE Greek king Antiochus IV). In later Antichrist traditions, the abomination of desolation became not an act (usually assumed to be Antiochus’ sacrifice to Zeus of a pig on the temple’s altar) but was personalised as the Antichrist, thereby aligning with Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians in which he talks of another Antichrist analogue referred to as ‘the man of sin, the son of perdition’ who not only takes his seat in the temple of God but declares himself to be God. Irenaeus in the second century of the Common Era was the first to consolidate these various strands, along with the little horn of the book of Daniel and the beast of Revelation, into a single figure identified as the Antichrist, and over the centuries, as Almond documents, more details would be added.

It is this approach that marks a welcomed difference between this work and McGinn’s denser and more obviously chronological Anti-Christ: Two Thousand Years of the Human Fascination with Evil. By beginning with the end, and then effectively having Christendom ‘show its work’ to explain how its vision of the Antichrist was arrived at, Almond underscores how the picture of the Antichrist developed over the first millennia from the smallest of scriptural crumbs and how by the time Adso composed his definitive biography, the monk was able to confidently narrate a story with a considerable amount of details not explicitly found in scripture. Key to this was the way in which speculation over the tiniest scriptural phrase or allusion, not to mention gematria and theological and eschatological mathematics, led to an accretion of popular and unquestioned key points, such as the idea that the Antichrist would be from the tribe of Dan. This was something first expounded by Irenaeus based on a decidedly creative reading of a verse from Jeremiah 8.16 (in which the city of Dan is meant, not the tribe, and where it is a victim of an invasion, not the source of a tyrant), and because the author of Revelation did not include Dan amongst the twelve tribes of Israel whose members would make up the 144,000 souls marked for salvation by God; a list from which the tribe of Ephraim is also missing, so who knows what they did wrong.

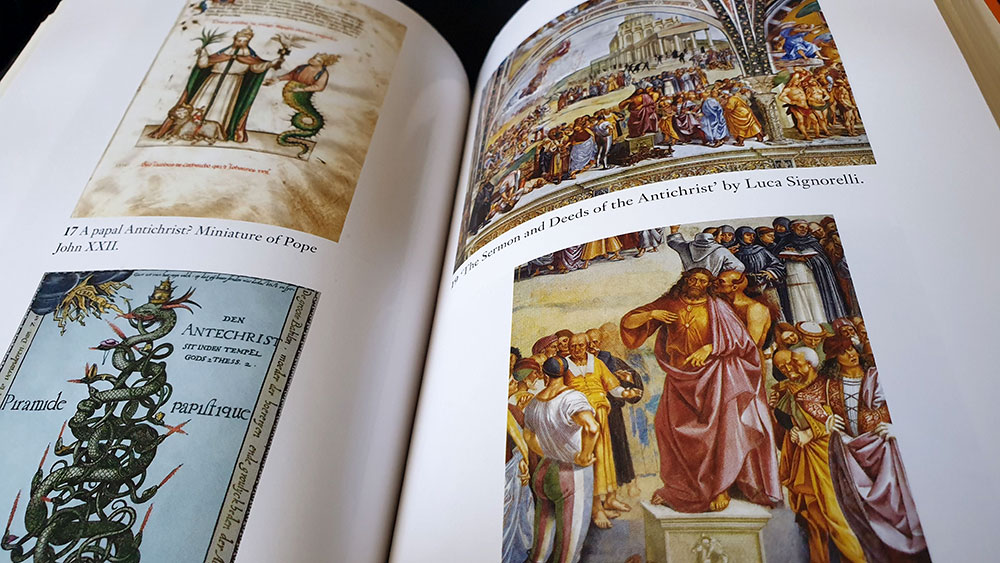

Due to this speculative accretion, a fairly complete idea of the Antichrist was in place by the end of the century, with the work of Irenaeus being joined by contributions from other including Hippolytus of Rome, Tertulian, Commodian, and the anonymous author of the Sibylline Oracles, with each bringing their own, though not always complimentary, additions to the lore. One of these is the quite delightful idea that the Antichrist was Nero, but not the living Nero as he was during his reign as Roman emperor but rather a future incarnation, who had either escaped death to wait in hiding, or who had returned from the dead in a sublime perversion of the resurrection of Christ. Five hundred years later, Adso’s influential vision of the Antichrist was still current, and can be seen in Luca Signorelli’s fresco The Preaching of the Antichrist, which, with its cast of apocalyptic characters and events, shows, as Almond puts it, Adso’s life of the Antichrist in pictorial form.

When it comes to the alternative idea of a papal Antichrist, Almond does not quite have the equivalent of Adso’s perfect summary, nothing that necessarily combined all the interpretation’s main elements. So rather than working backwards, Almond instead provides a further history of the conception of the Antichrist throughout the centuries, marking a trail of ideas, rather than explicit themes, which culminated in a then novel interpretation by the Cistercian monk Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135-1202). Almond shows how concerns about the Antichrist gradually evolved three hundred years into the Common Era and how, following the conversion of the Emperor Constantine in 312CE, Christianity was no longer the sole province of a persecuted faithful minority but was instead the dominant religion. With it now being hard to imagine an external tyrant persecuting a powerful Christian empire, a once imminent Armageddon was, for many, put on hold. Other than the exception of military leaders briefly figured as the Antichrist, such as the Vandal king Gaiseric or later the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, accusative fingers were now often pointed inwards. However, in these initial stages, there was no single Antichrist identified within the church, and instead a plurality of lowercase antichrists, the faithless hidden amongst the faithful, were excoriated for their hypocrisy, disbelief or heretical thoughts by luminaries such as Augustine, Tyconius, and Pope Gregory the Great. This intramural suspicion of other members thus imagined the body of the Antichrist as something active, like a virus, within the very body Christ that was the church. In 1190, Joachim of Fiore brought such ideas to their logical, singular conclusion when he told King Richard I of England, that the Antichrist was not only alive but had been born in Rome and would be elevated to the Apostolic See. While King Richard’s response, as recorded by Roger de Hoveden in his annals, was surprise, this idea would grow in popularity, with Joachim’s vision of a papal Antichrist equalling in spread and influence the older Adsonian tradition, particularly amongst Franciscans.

Almond continues his biography of the Antichrist down through the centuries, noting how both the Adsonian and Joachite traditions perpetuated and mutated, with expectations changing as events occurred and conditions for the arrival of the Antichrist evolved. One notable change was the addition of a multitude of other characters to the apocalyptic tableaux, including the heroic Last World Emperor, a restorative Angelic Pope, and sometimes even dual Antichrists: a mystical one and a martial one; while in the case of Ubertino of Casale, who seemingly couldn’t get enough of Antichrists, there would be two Mystical Antichrists (Boniface VIII and Benedict XI) as well as the final boss, the Great Antichrist.

Almond concludes in the modern era in which the decline of prophetic history from the middle of the nineteenth century lead to the idea of the Antichrist as a floating signifier, less associated with the apocalyptic and more a general critique of perceived evil in the world. Thus anyone, or anything, could be accused of being the Antichrist, be it a royal, a politician, or even entire religions or progressive social movements. Here Almond also turns his focus on literary and cinematic representations of the Antichrist, briefly summarising Rosemary’s Baby, the Omen trilogy, the Left Behind series, and in considerably greater detail, Vladimir Solovyov’s A Short Story of the Antichrist; but sadly, no Good Omens.

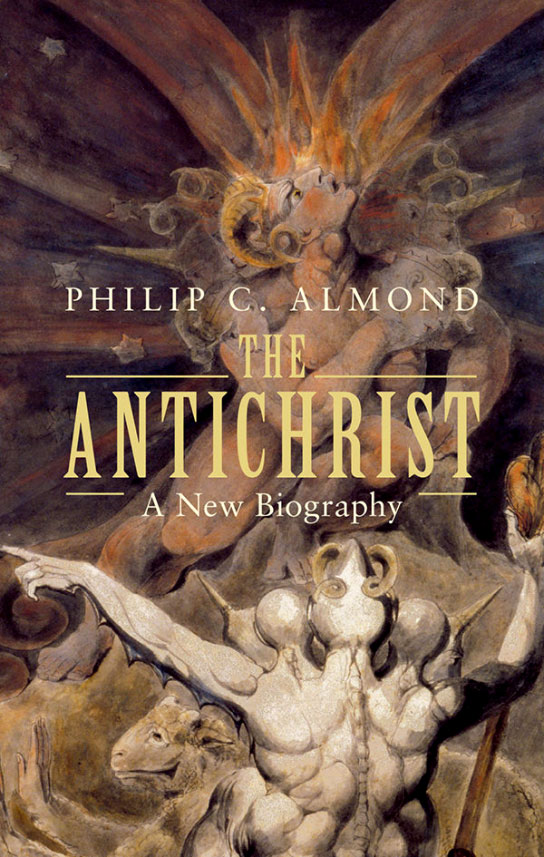

In all, this is an enjoyable read in which Almond’s pleasant narrative style belies a depth and thoroughness, acting as a testament to his familiarity with his subject. The Antichrist: A New Biography is presented as a hardcover edition bound in orange cloth, with title and author debossed in black on the spine, all wrapped up in a full colour dustjacket featuring William Blake’s rather fetching watercolour The Number of the Beast is 666 from 1805; continuing a Blakean pattern seen in Almond’s previous biographies. More colour is found in a section of colour plates towards the book’s centre, thirty images in all drawn from a variety of sources ranging from mid-eleventh century France to modern cinema. While each image has a caption describing it, there’s no specific title, credit, source or date included with it and the reader has to thumb back to an index of plates in the preamble for rather minimal information that could just as easily have annotated each image.

Published by Cambridge University Press