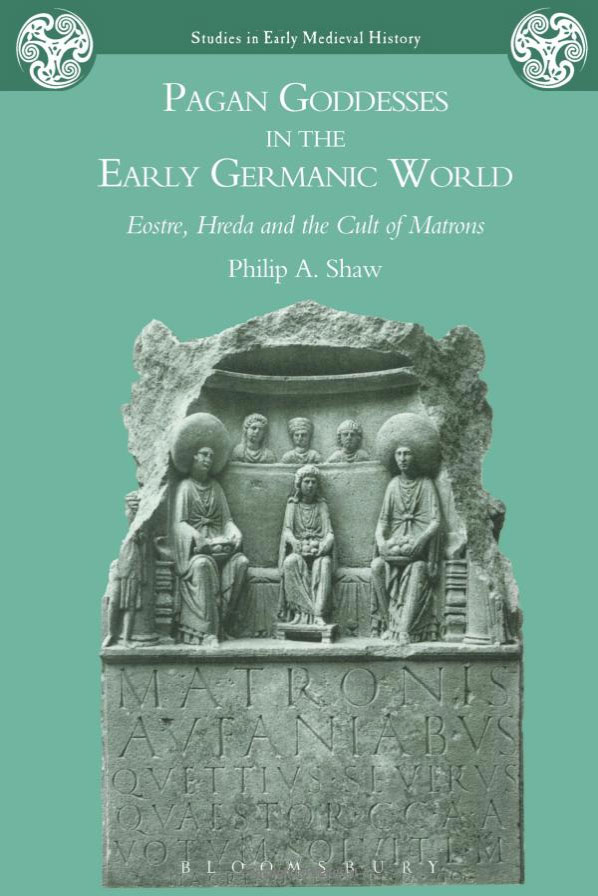

Subtitled Eostre, Hreda and the Cult of the Matrons, Philip Shaw’s book is an entry in Bristol Classical Press’ Studies in Early Medieval History, a collection of concise books on current areas of debate in antique and early medieval studies. Concise is indeed the word here, and this volume runs to just 100 pages, with a few more for references and index. This economy is fitting as the evidence for each of these goddesses is slight and anything more than this centurial content would arise suspicions about speculation and flights of the fanciful kind.

Subtitled Eostre, Hreda and the Cult of the Matrons, Philip Shaw’s book is an entry in Bristol Classical Press’ Studies in Early Medieval History, a collection of concise books on current areas of debate in antique and early medieval studies. Concise is indeed the word here, and this volume runs to just 100 pages, with a few more for references and index. This economy is fitting as the evidence for each of these goddesses is slight and anything more than this centurial content would arise suspicions about speculation and flights of the fanciful kind.

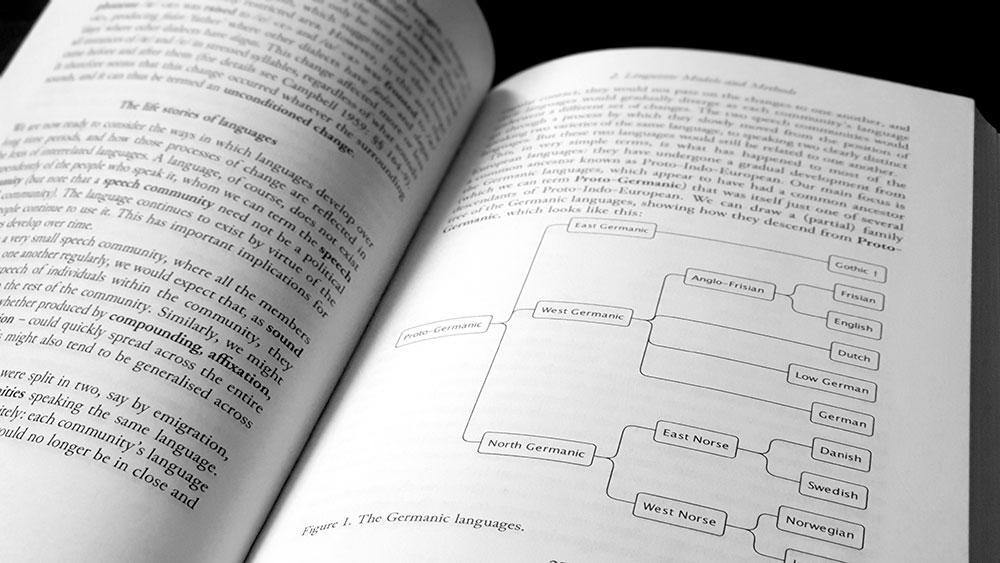

As it is, Shaw initially spends a fair amount of these hundred pages laying out his context and methodology, providing first a thorough presentation of his linguistic models, followed by an overview of the Romano-Germanic religious landscape of the Early Middle Ages. Given Shaw’s status as a Lecturer of English Language and Old English, it is the linguistic considerations that take the lion’s share here, with a section that he welcomes anyone with an understanding of the basics of word foundation, phonology and comparative reconstruction to skip; though you can’t help thinking that others without such expertise might take up that offer. If you’re not intimidated by the nomenclature, this chapter does act as an effective primer, presenting core phonological strategies, although without much reference to examples specific to the book’s concerns.

Things stay relatively broad in the next chapter’s discussion of the Romano-Germanic religious landscape of the Early Middle Ages, although Shaw uses it principally to outline the cult of the matronae, giving them the largest consideration here, alongside passing mentions of names for some of these Romano-German goddesses, often assumed to be associated with battle, such as Baudihillie and Friagabi. Shaw emphasises the local nature of the matronae cults, declining to attribute their presence and characteristic as part of any consistent and widespread Pan-Germanic belief system that would be comparable to the Scandinavian idea of the disir.

The two named goddesses discussed in this book have a common origin, appearing in the works of the Venerable Bede, whose De Temporum Ratione makes passing references to both goddesses in a discussion of Anglo-Saxon feast days and the names of the months. Hredmonath (March), he says, took its name from the goddess Hretha, to whom they sacrificed at this time of the year, while Eosturmonath (April), was named after a goddess called Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated that month. These enigmatic references are unique to Bede, with the names unattested elsewhere, though over the centuries, much cloth has been woven from these tiny strands.

The first of the named goddesses to receive attention here is Eostre, whose scant evidence hasn’t prevented an impressive accretion of ideas, as a multitude of glib, well-meaning, but ultimately erroneous Facebook posts about the true origins of Easter are testament. Shaw begins with an overview of Eostre as she has been perceived through the last two centuries of Germanic anthropology and philology, with Grimm being the most obvious figure, leading up to the present where caution has won out over speculation and a consensus has largely formed in which Bede’s linking of the festival’s name to this pre-Christian goddess is assumed to be discredited. Shaw appears unconvinced, and seeks to explore more, asking, as the chapter’s title does, whether Eostre is a Pan-Germanic goddess or simply an etymological fantasy. He has one trump in this study, compared to his historic counterparts, as their conclusions whether affirmative or negative were formed prior to the discovery in Germany’s Cologne region of votive images dedicated to what are referred to as the matronae Austriahenae. The presence of such figures incorporating a comparable German version of the Eostre name suggests that the venerable one was not simply making stuff up.

Without the benefit of archaeological adjuncts like the matronae Austriahenae, Shaw’s consideration of Bede’s other goddess, Hreda, is almost entirely etymological; and as such, feels a lot more unresolved. He explores various uses of similar words in Anglo-Saxon (hreod, hreda, hreðe, hreðan, hreð), seeing if any provide anything in the way of characteristics or function for Hreda as a goddess. But, other than associations with the concept of quickness (hræð), Shaw appears to find none that are particularly satisfying. Of more relevance for Shaw is the use of hreð as a personal name element, with variants appearing in the name lists of several libri vitae, and also in the word Hreðgotan, which is used as a name for the Goths in two Old English poems, all indicating a certain connection with specific unspecified places or peoples.

Shaw concludes with a chapter called Roles of the Northern Goddess? which casts as much shade as its enquiring title would suggest, referencing Hilda Ellis Davidson’s book of the same name and standing in contradistinction to her implicit idea of a single northern goddess whose facets are distributed amongst so many other goddesses. For those who find comfort in the idea of a consistent set of beliefs spread across pagan Europe and Scandinavia, with all the respect and surety that such a grand mythology offers, then the appeal here to the local, familial and even personal will be a disappointment. Shaw’s pragmatism is not soulless though, and rather than despairing at the lack of evidence for these goddesses, or our inevitably meagre understanding of what Anglo-Saxon paganism in general actually involved, he sees Eostre and Hreda as part of an intriguing, vast and diverse mythic landscape, one that is possibly more than half-submerged but still offers areas of further exploration.

Published by Bristol Classical Press.

Thank you to our supporters on Patreon especially Serifs tier patron Michael Craft.