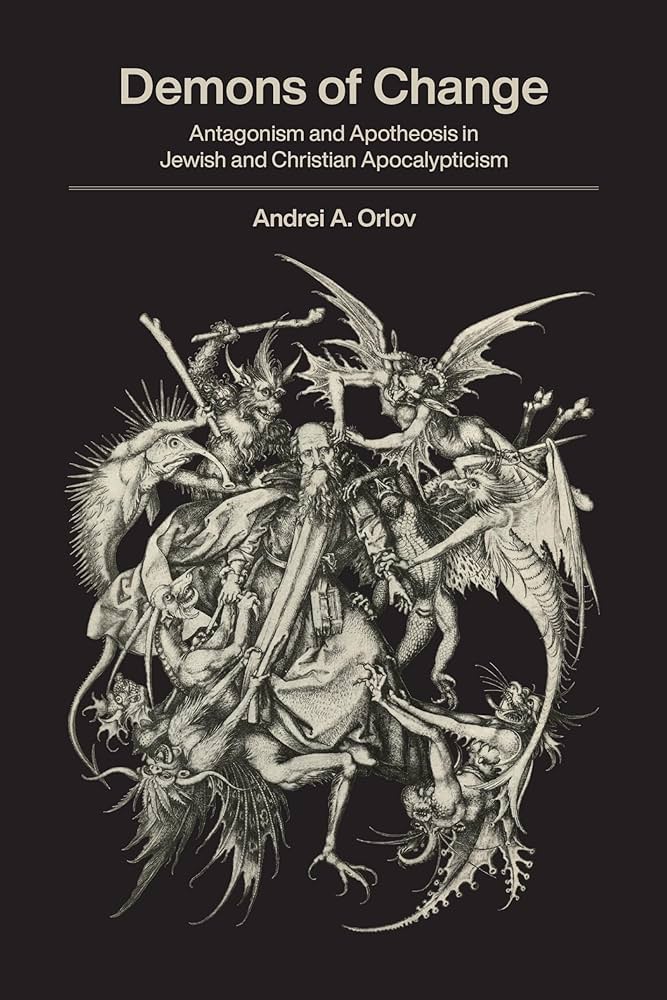

In the previously-reviewed Demons of Change, Andrei A. Orlov devoted one of his chapters to the idea that the sash worn by the Hebrew High Priest symbolised Leviathan, participating in a sub-microcosmic representation of the cosmos that also mirrored the microcosmic design of the temple at Jerusalem. That relatively slight chapter touched on the cosmological and eschatological qualities of the primordial serpent, but here, in Supernal Serpent, Leviathan receives the full-length hardback treatment with an extensive study that includes both Judaism and Christianity. As is Orlov’s wont, though, the lens for this endeavour is provided by the Slavonic recension of The Apocalypse of Abraham, a pseudepigraphon, written sometime in the first or second century CE that acts as a frequent touchstone for him. It is genuinely remarkable how much material Orlov has managed to generate using The Apocalypse of Abraham as his source, with the aforementioned Demons of Change drawing strongly from it in its consideration of demonic and angel antagonism, while two earlier, but as yet unreviewed, titles, Dark Mirrors and Divine Scapegoats, both drew on the pseudepigraphon for their assessment of Satanael. This approach is particularly evident in how although the apocalypses’ references to Leviathan are so slight, something that could have been missed in passing, Orlov is able to use these cosmological gems as a gateway into far wider explorations.

In the previously-reviewed Demons of Change, Andrei A. Orlov devoted one of his chapters to the idea that the sash worn by the Hebrew High Priest symbolised Leviathan, participating in a sub-microcosmic representation of the cosmos that also mirrored the microcosmic design of the temple at Jerusalem. That relatively slight chapter touched on the cosmological and eschatological qualities of the primordial serpent, but here, in Supernal Serpent, Leviathan receives the full-length hardback treatment with an extensive study that includes both Judaism and Christianity. As is Orlov’s wont, though, the lens for this endeavour is provided by the Slavonic recension of The Apocalypse of Abraham, a pseudepigraphon, written sometime in the first or second century CE that acts as a frequent touchstone for him. It is genuinely remarkable how much material Orlov has managed to generate using The Apocalypse of Abraham as his source, with the aforementioned Demons of Change drawing strongly from it in its consideration of demonic and angel antagonism, while two earlier, but as yet unreviewed, titles, Dark Mirrors and Divine Scapegoats, both drew on the pseudepigraphon for their assessment of Satanael. This approach is particularly evident in how although the apocalypses’ references to Leviathan are so slight, something that could have been missed in passing, Orlov is able to use these cosmological gems as a gateway into far wider explorations.

Orlov divides this supernal serpent into just five parts, the first of these chapters opening with a discussion of Leviathan’s theophany, using as its thematic seed a scene in the Apocalypse of Abraham in which the patriarch experiences a cosmogonic vision. Gazing downwards, Abraham sees the earth and the underworld below him, seemingly created as a mirror of heaven, with Leviathan identified as a foundation upon which this world lies: “Leviathan and his domain, and his lair, and his dens, and the world which lies upon him, and his motions and the destruction of the world because of him.” Orlov seeks confirmation of this distinctive imagery in the biblical book of Job, addressing not, for now, the idea of Leviathan as a cosmological force but rather as a divine one, a mirror of God with whom he seems to share theophanic characteristics. In Job and in later mystical Jewish and accounts rabbinic speculation, Leviathan appears not simply as a monstrous creature but a numinous one, a being of aureate light and luminescence, breathing fire and exhaling smoke (attributes associated with gods throughout the Levant).

The cosmic centrality afforded Leviathan in the Apocalypse of Abraham provides the basis for the second chapter’s discussion on his role as the Axis Mundi. Despite the brevity of references to this function in the apocalypse, this is one of the longer chapters as Orlov is able to find similar axial concepts in a range of literatures, including direct biblical accounts, Enochic material, Islamic tradition, Rabbinic speculation, and later Jewish mysticism, including the Zohar. Some directly relate to Leviathan, whilst others reference similar antediluvian figures, such as Behemoth, the Watchers (who in the Book of the Watchers are punished by becoming pillars of cosmic stability), and Satan (who in the Slavonic apocryphal text About All Creation, is tied to a cosmological pillar made of adamantine). Orlov expands this theme into a broader consideration of Leviathan’s cosmological and topographical role, documenting the multitude of textual examples in which this is discussed, including, albeit briefly, instances in which the tellurian waterways associated with the dragon are envisioned as avenues for the transmission of energies from the Sitra Achra.

In chapter three, Orlov turns to a different section of the Apocalypse of Abraham to consider the relationship between Leviathan and Yahoel, an angelic protagonist who defines his raison d’être as being to “rule over the Leviathans, since the attack and the threat of every reptile are subjugated to me.” Before getting directly to Yahoel, Orlov uses this quote to reiterate the idea of multiple Leviathans, or instances in which Leviathan is twinned with some other creature such as Behemoth; some in contrasting gender designations as apocalyptic-incepting mates, but others not. As a theme that was touched on earlier in the general discussion of Leviathan’s theophany, this can feel, depending on degrees of severity, either slightly familiar or very repetitive, especially as many of the previous sources are requoted again in their entirety. Orlov compares Yahoel’s function in opposing Leviathan to similar antagonistic pairings in West Asian mythology (Marduk and Tiamat, Baal and Yamm), before drawing comparisons with his angelic brethren Raphael and Gabriel. The final and most complete comparison is with God himself, as Yahoel’s victorious function mirrors that found in the words of the Psalmist, where Yahweh is depicted complete in his victory over Leviathan or its analogues such as Rahab. This is made all the more striking by Yahoel appearing to effectively be a hypostasis of Yahweh, identifying themselves explicitly as “a power in the midst of the Ineffable who put together his names in me;” something which can be seen in the name’s combination of two theophoric elements, yah- and –el.

For his fourth chapter, Leviathan and the Temple, Orlov returns to the theme briefly touched upon in his book Demons of Change: the symbolism of the macrocosmic Leviathan hidden in the architecture and costumes of the microcosmic sacerdotal. As one can imagine, this consideration is pretty light on explicit corroborative examples, so instead, this chapter spends the bulk of its time returning to ideas of Leviathan’s cosmological function, as well as broader ideas of temple symbolism as emblematic of an intersection betwixt the macrocosmic and the microcosmic, such as the veil that protects the Holy of Holies, or the Foundation Stone upon which the temple was built. Leviathan plays a role here in some interpretations of the Foundation Stone, but can also be found in instances in which the primordial waters and their encompassing of the world are represented in sacramental architecture, such as the outer courtyard of the cosmological temple.

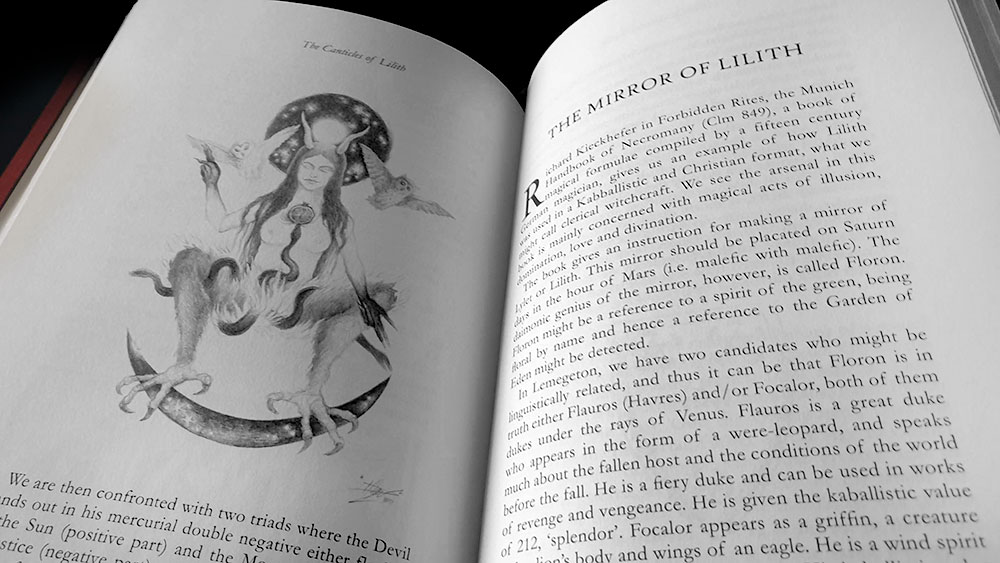

Orlov concludes with his fifth chapter, titled somewhat enigmatically, but intriguingly, Leviathan and the Mysteries of Evil, which shows how Leviathan was not simply a figure of monstrosity and antagonism but a source of knowledge. For darker-inclined occultists, this makes for interesting reading, with Orlov providing a whole raft of examples in which interactions with Leviathan are effectively attempts at acquiring knowledge from the Sitra Achra, often through an abyssal or chthonic descent. As a theophanic figure who mirrors the divine in power and incomprehensible glory, Leviathan acts as an encapsulation of numinous mysteries, be it as a eschatological sacrament (whose flesh is eaten by the righteous in the end times), or as an embodiment of the cosmos, the knowledge of which gives insight into the mysteries of creation. Events such as Jonah’s experience in the belly of the whale, the lifting up of the Nehushtan serpent of bronze by Moses in the Book of Numbers, the baptism of Jesus in the river Jordan, and Abraham’s subterranean descent in his eponymous apocalypse, as well as many others, each acts as a piece of this puzzle, one which, when viewed in concert, makes for a convincing case. Most striking is the suggestion that the extensive description of Leviathan’s characteristics and dimension given in the book of Job provided an inversion of Shi’ur Qomah inspired mysticism (in which the measurement of God’s divine body act as a source of meditation), allowing one to use the great dragon in a similar fashion.

This is a book with much to recommend it, especially in its treatment of Leviathan as a source of wisdom. Orlov effortlessly navigates his source texts, always finding prior speculative or textual confirmation for each interpretation. Supernal Serpent runs to 347 pages and is hardbound with a beautiful dustjacket designed by James R. Perales that incorporates a detail of St. Michael from Jan van Eyck’s Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych. The stock is a beautiful, slightly cream and pleasant to the touch, with text effortlessly but practically formatted in comfortably leading and tracking for ease of reading.

Published by Oxford University Press