David Chaim Smith, as his bio runs, is an author and artist based on Long Island, New York. He gained a BFA in drawing from Rhode Island School of Design and graduated from Columbia University with a Masters in 1989. His principle medium is finely rendered and intensely detailed pencil, and that’s what you get here in this large-format book from Fulgur; his second with that press, following on from 2012’s The Sacrificial Universe.

David Chaim Smith, as his bio runs, is an author and artist based on Long Island, New York. He gained a BFA in drawing from Rhode Island School of Design and graduated from Columbia University with a Masters in 1989. His principle medium is finely rendered and intensely detailed pencil, and that’s what you get here in this large-format book from Fulgur; his second with that press, following on from 2012’s The Sacrificial Universe.

The Blazing Dew of Stars presents David Chaim Smith’s take on qabalah, otherwise seen in titles such as 2015’s The Kabbalistic Mirror of Genesis and 2016’s The Awakening Ground: A Guide to Contemplative Mysticism (both from Inner Traditions). Where those books differ from The Blazing Dew of Stars is the focus on Chaim Smith’s artwork, often appearing here as full page plates, with adjunct smaller illustrations in the margins of facing pages. That doesn’t mean this book is without writing, in fact, it is quite text heavy, with Chaim Smith’s images appearing as adjuncts to his dense, periphrastic text. It’s just such text that forms the first, and image-free, chapter, Reaching Beyond God, 24 pages of circumlocutory writing with phrases like “systems that cultivate compassion mitigate the primitive reflexes of animal power that produce the psycho-emotive toxins of the human realm” or “Conceptuality can slowly learn to be able to abide within it, such that subtle abstract impressions can slowly take over, subsuming the momentum of perceptual formation into visionary registers.” As your eyes glaze over after page after page of this, you find yourself skipping forward, hoping to hit the pretty pictures sometime soon; the ligatures on the serif typeface are nice, though, if a little showy.

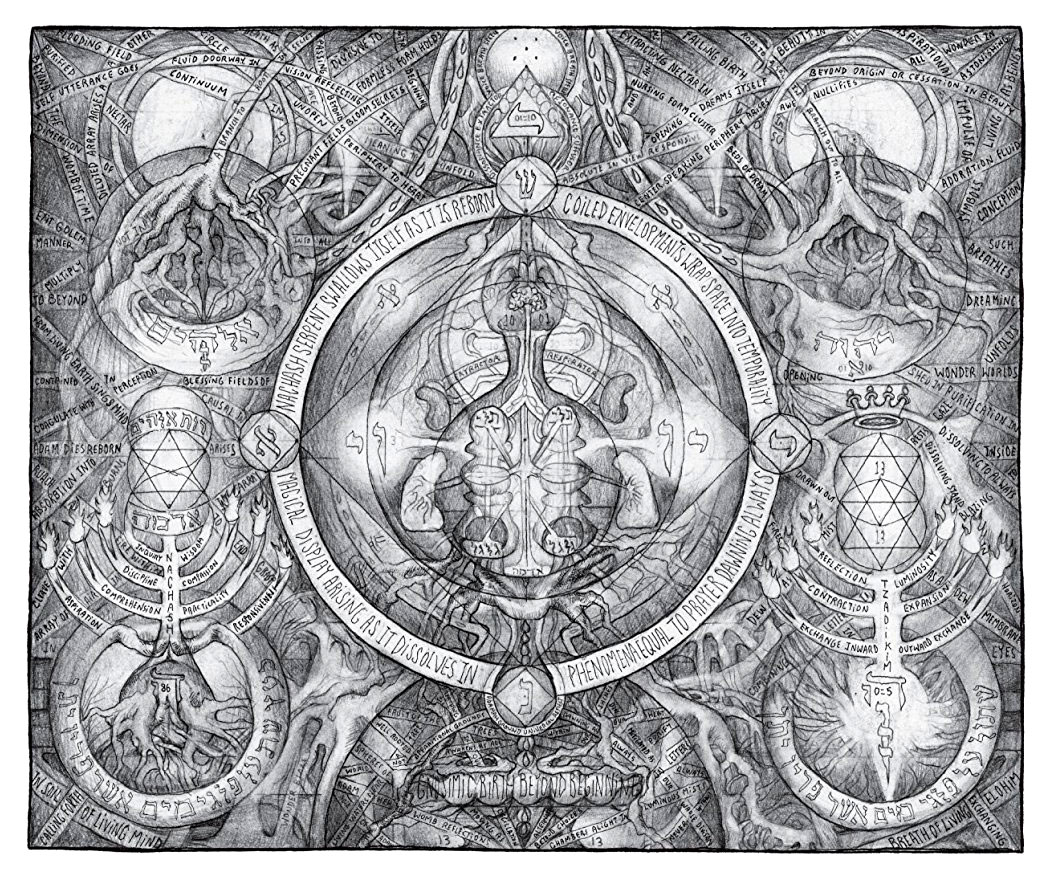

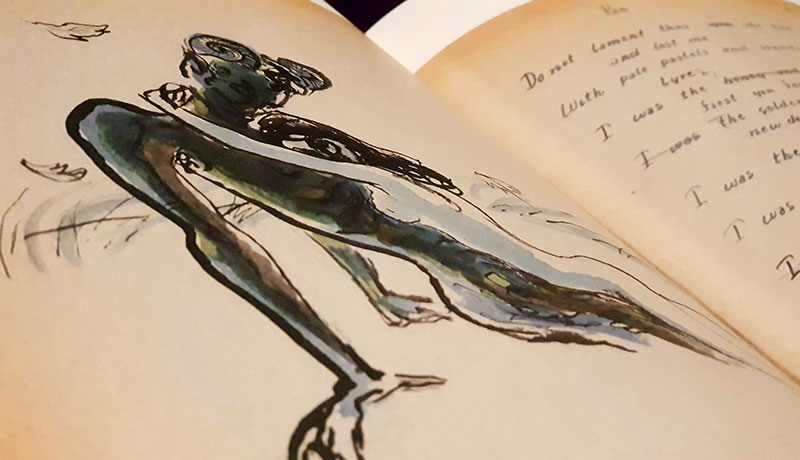

Chaim Smith presents what he refers to as kabbalistic contemplative alchemy, a system he calls Iy’yun; a Hebrew word, sans the glottal stop, meaning ‘contemplation.’ Iy’yun is pursued, in this case in particular, through linguistic and graphic constructions, with its inner life creating resonating layers, revealed within the illustrations here, and it is this that distils the dew of the title; a gnostic realisation which accumulates with wonder, beauty and astonishment. Or so the blurb goes. This takes the form in a manner of ways: exegetical sections, more practical exercises in which Chaim Smith’s images are a meditative focus, and other exercises in which the illustrations are but representations of the concept in hand.

The dense and theoretical first chapter opening The Blazing Dew of Stars is followed by one that reprises the title of the book as its own and is subtitled A Kavanah Meditation in Three Parts. This three part meditation is based on three chambers, each focussed on a divine name: AHYH, ALP LMD HY YVD MM, and YHVH/MTzPTz. Chaim Smith provides a thorough exegesis on the metaphysics behind the procedure, in which the dew of contemplation is brought forth, the blaze is set alight, and the practitioner becomes a primordial mirror, a “liquid display of transelemental morphosis,” no less. This is then followed by the exercise itself, in which the various letters are visualised doing their thing, and which is, in turn, depicted graphically in Chaim Smith’s accompanying pencil illustration.

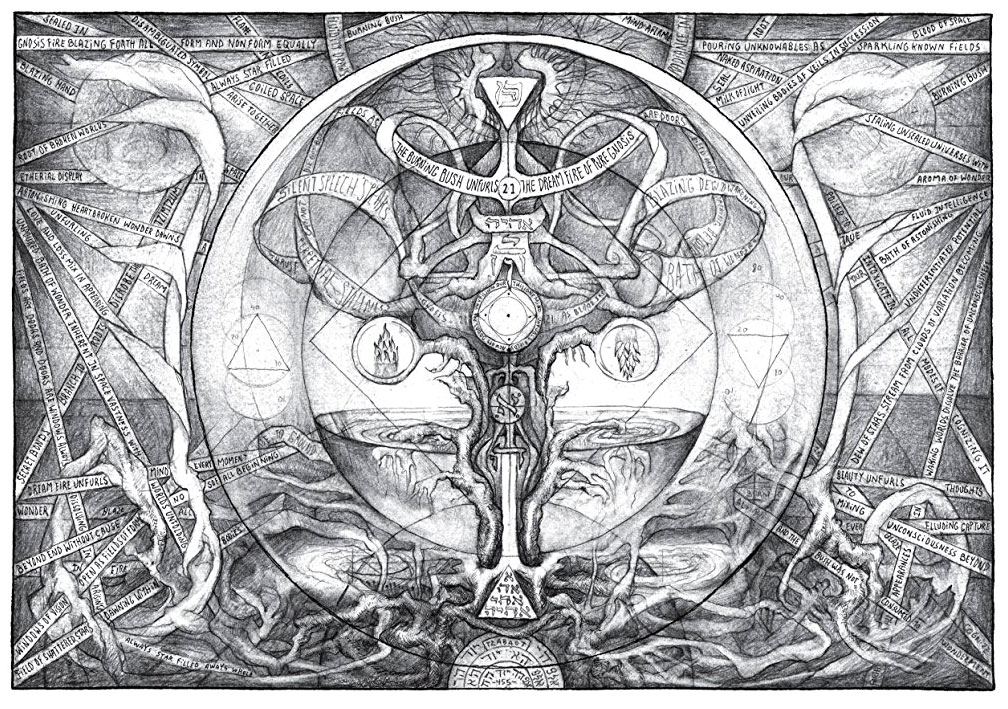

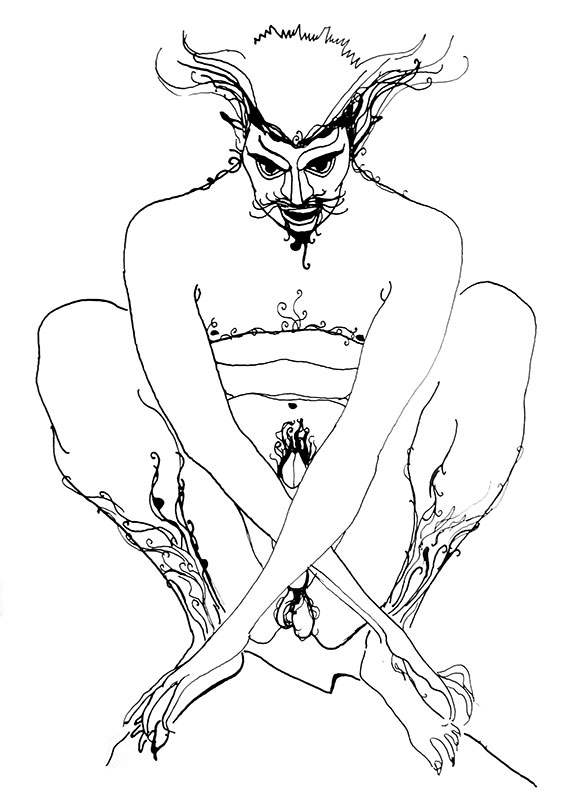

The third chapter, Unfurling the Dream Fire, is the book’s largest and most visually impressive section, in which Chaim Smith conveys ideas through four different methods: two textual and two graphical. Each spread begins with a usually brief verse, set in a large italic face, and this is then expanded upon below it in the smaller text of technical notes, featuring definitions, correspondences, and numerological values. The ideas contained within the initial quote are distilled into small, relatively simple, seals that sit in the right margin of the right hand page of a spread, while the left page is taken up entirely by considerably more elaborate elucidations of the ideas as full page illustrations. The idea, says Chaim Smith, is that the contemplator is able to overlap and interpenetrate meaning using a variety of mental tools.

The full page formatting of the images in Unfurling the Dream Fire allows them to be seen in all their glory, and execution. They are densely rendered almost entirely in just pencil; something that you don’t necessarily notice until you are viewing them at this size, where the smudged layers of graphite used for shading or as background can look murky and less impressive than at first glance. With his images featuring an abundance of alembics and other glass vessels, as well as the roots, trunks and branches of mystical trees, the most obvious comparison of Chaim Smith’s work are alchemical illustrations; notably those that accompany the work of fifteenth century alchemist George Ripley, such as the scroll that bears his name. There’s a persistent sense of growth and fluidity, of amrita dripping from receptacles and homunculi growing in cucurbits. All of the elements are contained within often circular borders, as well as boundaries created by text, often repeating the lines of the initial verse, or evoking key words. The same four-fold format is also followed in a later section, The Enthroning of the Blaze.

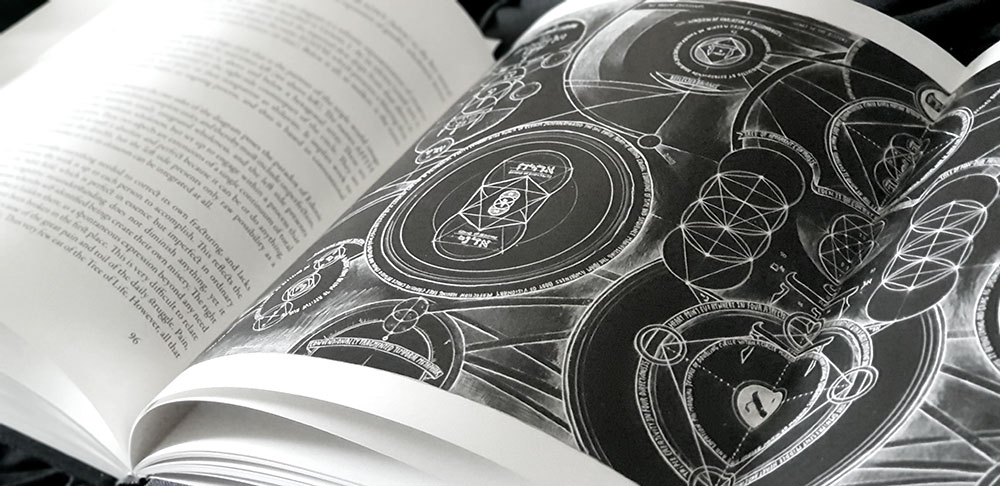

Several other sections follow Unfurling the Dream Fire, largely text based but accompanied with the occasional full-page image, including some instances where the illustrations are inverted, giving the impression of scratchboard or chalk on a black board. One of these, Dead Dreams Awaken the Sleeping Bride, is effectively a guided visualisation, heavy on exegesis within the journey text, accompanied by a single full-page illustration. Meanwhile, The Intoxicating Nectar of Vision, a received text of ten numbered verses that runs parallel to the creation narrative of the opening of Genesis, and which, naturally, follows the style and nomenclature of the rest of The Blazing Dew of Stars. This is an argot full of words such as transcendence, perceptual matrices, resonances and magical continuums; all lexemes that in their disorientating concatenation are often teetering on the edge of a word salad abyss.

The regular edition of The Blazing Dew of Stars consists of 913 copies, measuring 27cm square with 138 pages in total, and 14 full page drawings, 29 seals and vignettes and a two-page folding plate of The Metacartograph, a large format, colour inverted illustration that acts as an “overview map of creativity in the manifestation of phenomena,” if you will. This edition is bound in black cloth, with a matte finish black dustjacket. The deluxe edition of 88 author-signed copies was bound by hand in full black morocco with special tooling in silver gilt, blind pressed and silver filled front panel embellishment. It included the dust jacket of the standard edition but was housed in a special lined slipcase of premium black cloth.

Published by Fulgur