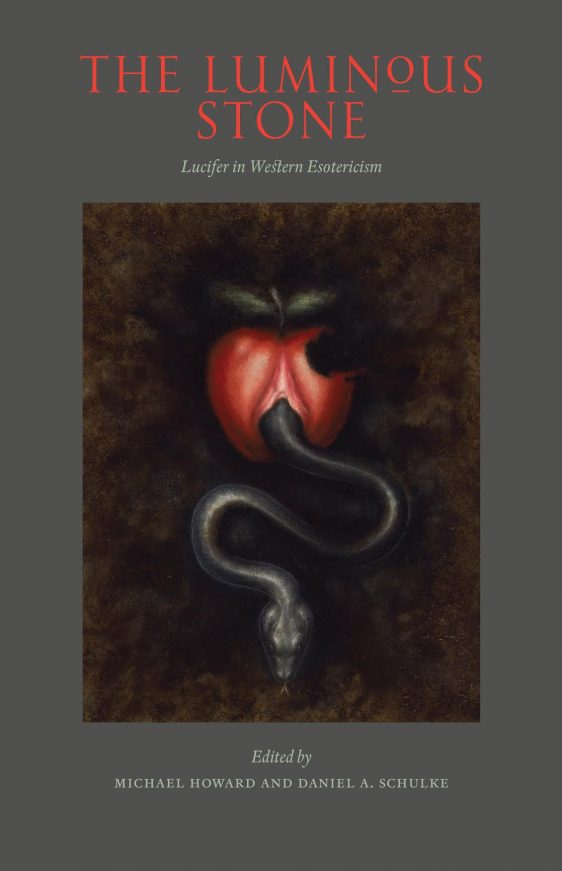

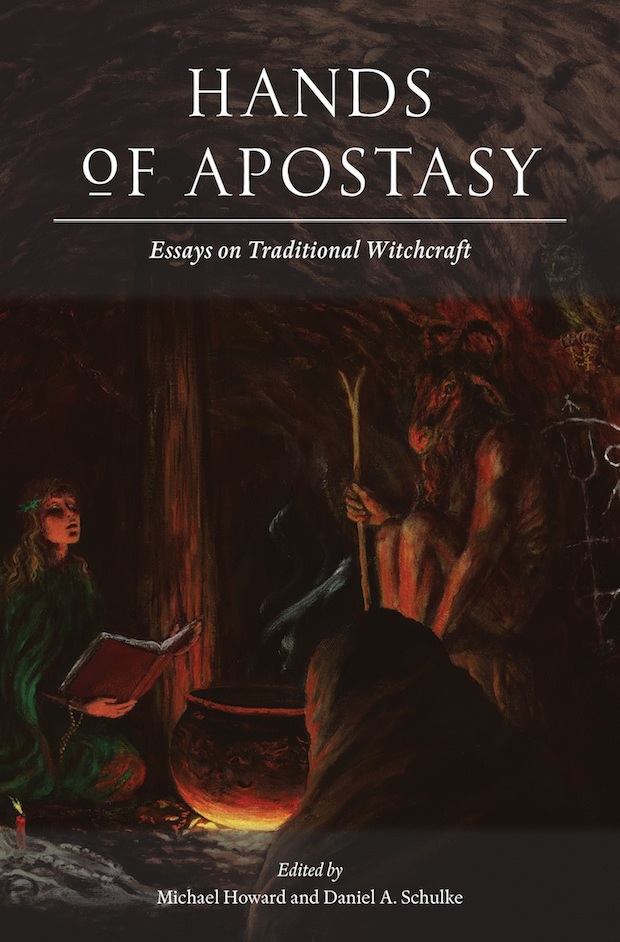

Focusing its attention on the figure of Babalon, A Rose Veiled in Black is the second volume in Western Esotericism in Context, a series from Three Hands Press which began with the previously reviewed Hands of Apostasy and continued with the also reviewed Luminous Stone. It features essays from ten writers: Amodali, Robert Stein, Erik Davis, Caroline Wise, Daniel A. Schulke, Frater A.I., Gordan Djurdjevic, Grant Potts, Manon Hedenborg-White, Richard Kaczynski and Robert Fitzgerald. Along with these written pieces are visual contributions from names both familiar and unfamiliar: Barry William Hale, Hana Lee, Linda MacFarlane, Liv Rainey-Smith, Mitchell Nolte, Nicole DiMucci Potts, Sarah Lindsay and Timo Ketola.

Focusing its attention on the figure of Babalon, A Rose Veiled in Black is the second volume in Western Esotericism in Context, a series from Three Hands Press which began with the previously reviewed Hands of Apostasy and continued with the also reviewed Luminous Stone. It features essays from ten writers: Amodali, Robert Stein, Erik Davis, Caroline Wise, Daniel A. Schulke, Frater A.I., Gordan Djurdjevic, Grant Potts, Manon Hedenborg-White, Richard Kaczynski and Robert Fitzgerald. Along with these written pieces are visual contributions from names both familiar and unfamiliar: Barry William Hale, Hana Lee, Linda MacFarlane, Liv Rainey-Smith, Mitchell Nolte, Nicole DiMucci Potts, Sarah Lindsay and Timo Ketola.

Aleister Crowley naturally looms large within these pages, and co-editor Robert Fitzgerald kicks things off with a discussion of the various appearances of, and allusions to, Babalon in the Master Therion’s The Vision and the Voice, his record of travelling through the Enochian aethyrs. This is a text that is cited time and time again throughout A Rose Veiled in Black and Gordan Djurdjevic covers similar ground to Fitzgerald, but also surveys the glimpses of Babalon that can be gleaned in The Book of the Law, and briefly touches on Leah Hirsig’s relationship with Crowley and Babalon herself. Hirsig gets more of her own focus in “I am Babalon,” a piece by Richard Kaczynski, who fastidiously documents the life, before and after Crowley, of the woman who identified herself as Babalon and as the mother of several magical children, including Crowley’s subsequent Scarlet Woman, Dorothy Olsen.

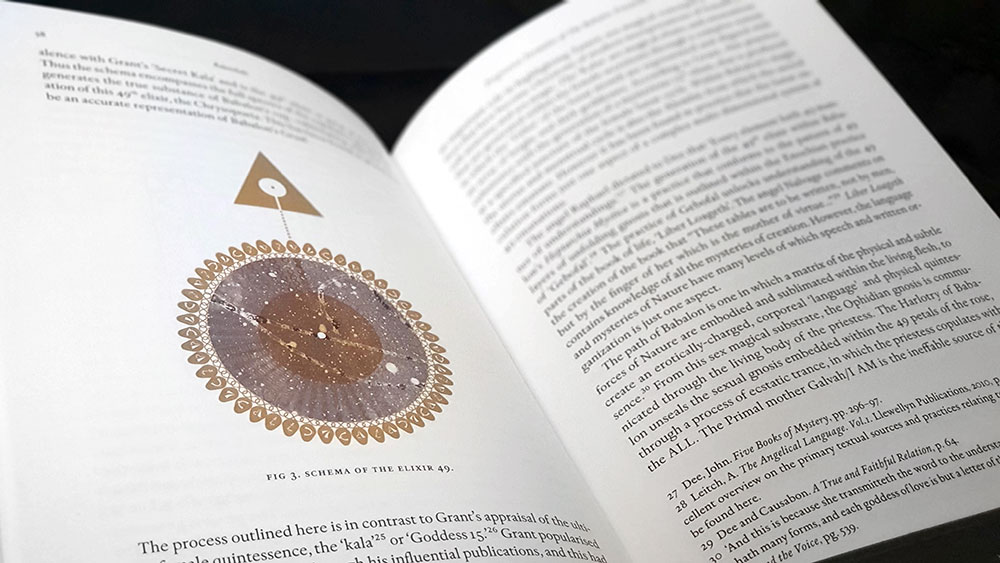

A more experiential approach comes from Amodali of Mother Destruction/Sixth Comm fame, whose wonderfully-verbose-titled Introductory Theoria on Progressive Formulas of the Babalon Priestesshood addresses what she sees as fundamental misinterpretations and distortions of the archetypes and formulas of the sexual gnosis key to Babalon’s magic. To this end, Amodali draws on her over 25 years of magical experience to present a ritual formula, informed by Dr John Dee’s De Heptarchia Mystica, in which practitioners forge the Body of Babalon, in a tasty taster of her long-forthcoming title The Marks of Teth from Three Hands Press.

Other contributors offer practical options too, either as instruction or documentation, with Robert C. Stein detailing a Liber Nu-based working he performed in Australia in 1985, within an asteroid or comet-formed crater under a sky occupied, as above, so below, by Halley’s Comet. Meanwhile, in Seven Chalices of the Lady, Grant Potts presents a group rite, originally performed at the Bubastis Oasis OTO, Texas, in 2013. Drawing on a Red Tara practice from the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, the rite associates the chakras with the seven Babalonian chalices of the title, seeking to attune the body of light to the Thelemic current and the mysteries of Babalon.

Towards the end of A Rose Veiled in Black, co-editor Fitzgerald returns to make his own practical septenary contribution with a Rite of the Seven Keys of the Kingdom, a ritual for achieving communion and congressus with Babalon, with liturgy drawn from the Enochian keys, The Vision and the Voice, Liber Cheth vel Vallum Abiegni and Dee and Edward Kelley’s original 1587 transmission from the Daughter of Fortitude. Fiztgerald’s partner in editing, Daniel Schulke, meanwhile, provides a lengthy meditation on Babalon’s theme of abomination, which he relates to the quintessentially Cultus Sabbati taboo-breaking Formulae of Opposition and abjection; though that latter post-structuralist terminology is not used here. Schulke effectively makes an unstated case for the release of this book by a publishing house more often associated with witchcraft, contemplating the relationship betwixt Babalon, Abomination and witchcraft. He draws intersections between Babalon’s cup of fornications and the witches’ cauldron, and highlights other ways in which her imagery has analogues in the systems of the Cultus Sabbati. Then, of course, there’s John Whiteside Parsons, who definitively referred to his Babalon-focused system as The Witchcraft.

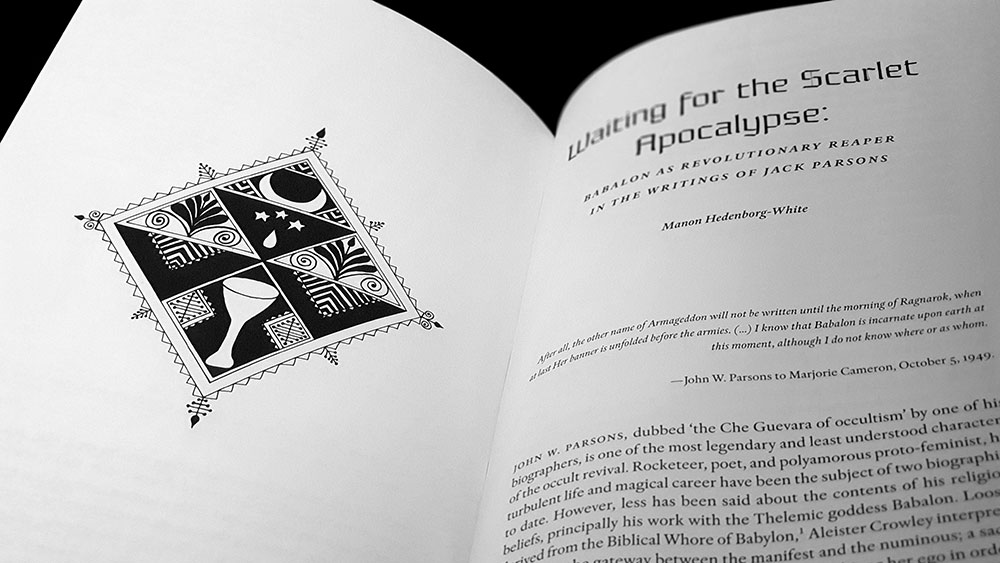

Next to Uncle Al, Parsons is the Babalon devotee who gets the most mileage in A Rose Veiled in Black, with Manon Hedenborg-White giving over a substantial 33 pages to Uncle Jack and his place in the mythos of Babalon. Hedenborg-White begins with a solid history of Parsons and his various interactions with Babalon (citing extensively from George Pendle’s Strange Angel) before devoting a significant amount of space to highlighting the difference between his conception of Babalon and that of Crowley. While the Babalon of Crowley’s The Vision and the Voice is removed, residing in the astral, and largely passive, Parsons’ Babalon is a goddess with agency and the ability, and will, to move into the material realm, giving orders and fomenting revolution.

This view is something also explored by Erik Davis in Babalon Rising: Jacks Parsons’ Witchcraft Prophecy, in which he describes it as emblematic of Parsons’ “magickal feminism.” Both Davis and Hedenborg-White portray Parsons and his vision of Babalon as being ahead of its time, with the contrast between Californian Uncle Jack and the Victorian Crowley being particularly notable; though Davis does not shy away from calling Parson’s earnest views somewhat essentialist and slightly cheesy. The fulfilment of Parsons’ witchcraft prophecy, which had predated even Gerald Gardner’s publication of Witchcraft Today in 1954, saw the growth of witchcraft as a counterculture, often feminist, movement, in the latter half of the 20th century; with Davis suggesting it was no accident that the particularly militant and vociferous strands began in Los Angeles.

Perhaps the most outlier of contributions here comes from Caroline Wise who almost admits as much in the narrative of her Dreaming of Babalon and the Bride of the Land. This begins abruptly, placing the reader in an unexpected narrative in which Wise is flying, quite reflectively and with great clarity, over the landscape of Glastonbury in what one eventually realises is a dream experience. It ends with flashes of the number 156 and a message from Babalon instructing Wise to ‘find me in this land.’ Wise’s work has always had a sense of the geographical about it, in particular her many pages spent on the road goddess Elen, and this is what occurs here, with her following Babalon’s directive and seeking to find her within the magical landscape of Glastonbury. This draws heavily on Katherine Maltwood’s idea of the Glastonbury Zodiac, great (theoretical) landforms within the region’s hills, streams and roads that appear to represent the twelve signs of the zodiac, with Wise’s journey predominantly focusing on themes of the grail cup, the constellation of Virgo and echoes of Mary Magdalene.

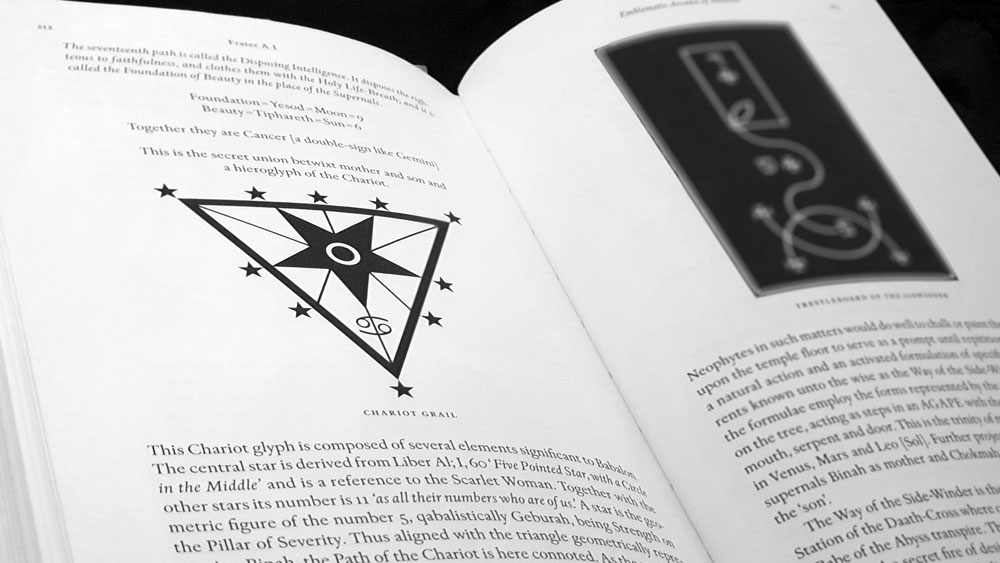

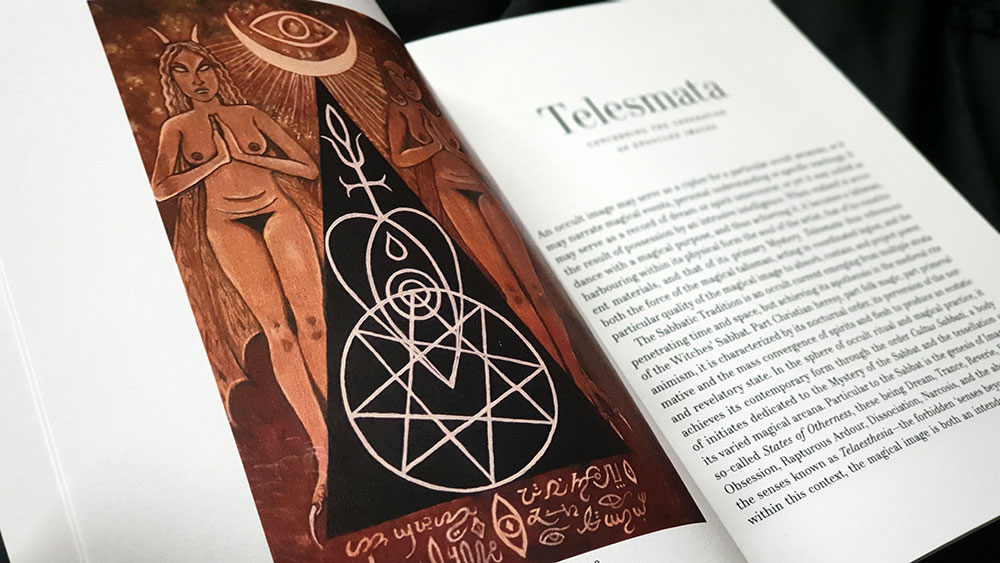

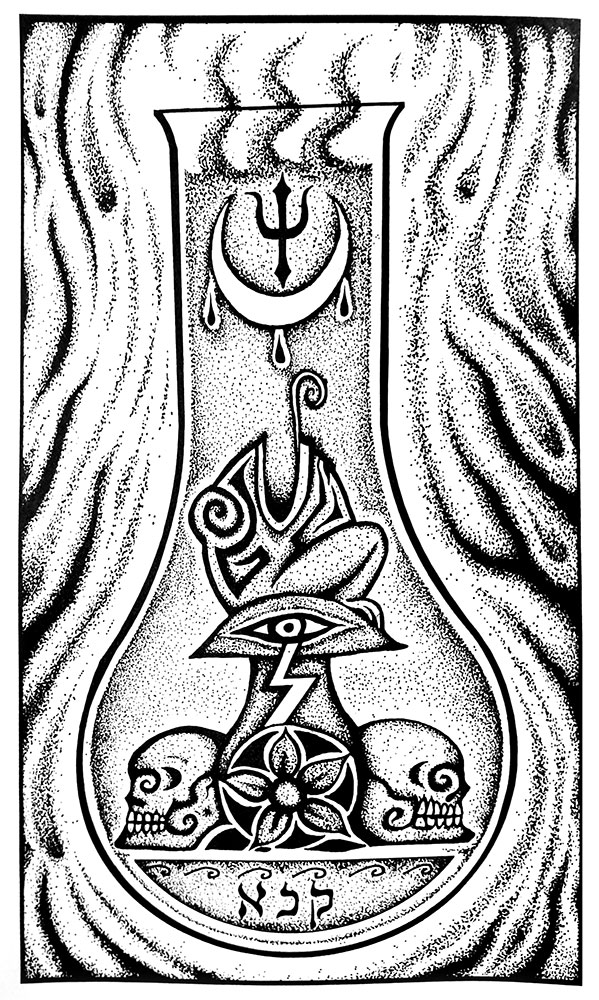

A Rose Veiled in Black concludes with another distinct approach, with Frater A.I.’s Emblematic Arcana of Babalon, in which he provides a meditation on certain themes and symbolism associated with Babalon, represented as a series of sigils and emblems. Reminiscent in some places of Hagen von Tulien’s stark black and white designs, these images draw on commentary from The Vision and the Voice along with tarot and qabbalistic symbolism to illustrate concepts such as Babalon as the disposing intelligence of Cain, her seven-headed mount and the City of Pyramids, and the Egg of the Babe of the Abyss.

In all, there is a wide variety of work in A Rose Veiled in Black, ranging from good to great, and with no obvious missteps or huge dips in quality. The work is proofed fairly well, with only a few howlers slipping by: in his piece on Leah Hirsig, Kaczynski quotes from the Gnostic Mass and has Chaos as the sole “Viecregent” of the Sun, rather than, surely, ‘viceregent,’ while Hedenborg-White’s piece has one instance in which the names of Babalon and Parsons are transposed, leading to the head scratching genderfuck of “the goddess asks Babalon to give his mortal life in exchange for her incarnation… Parson responds: ‘I am willing.’”

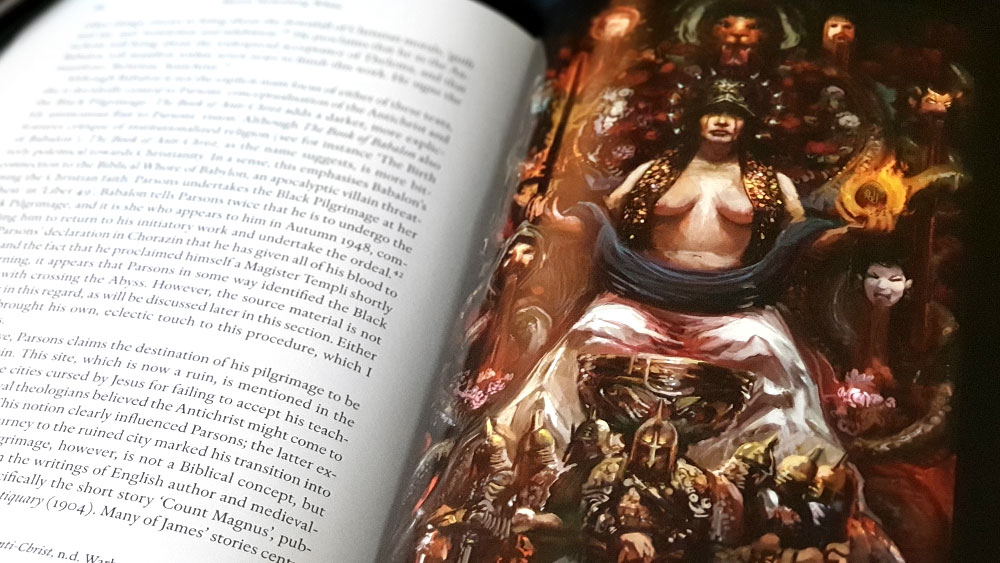

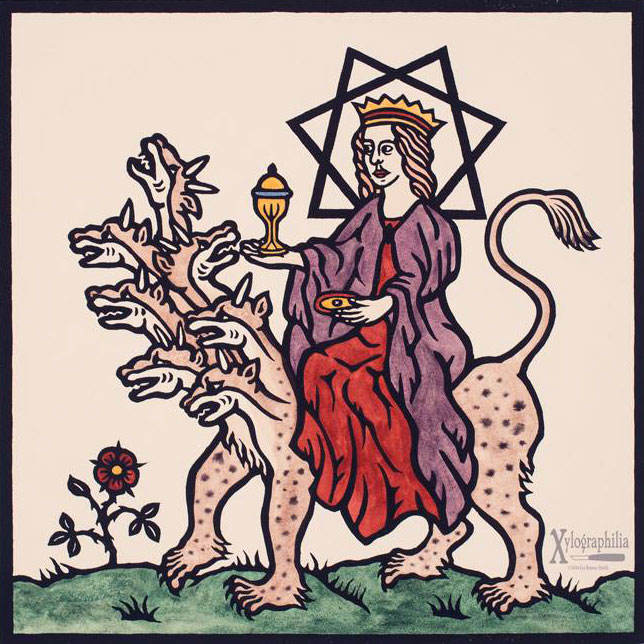

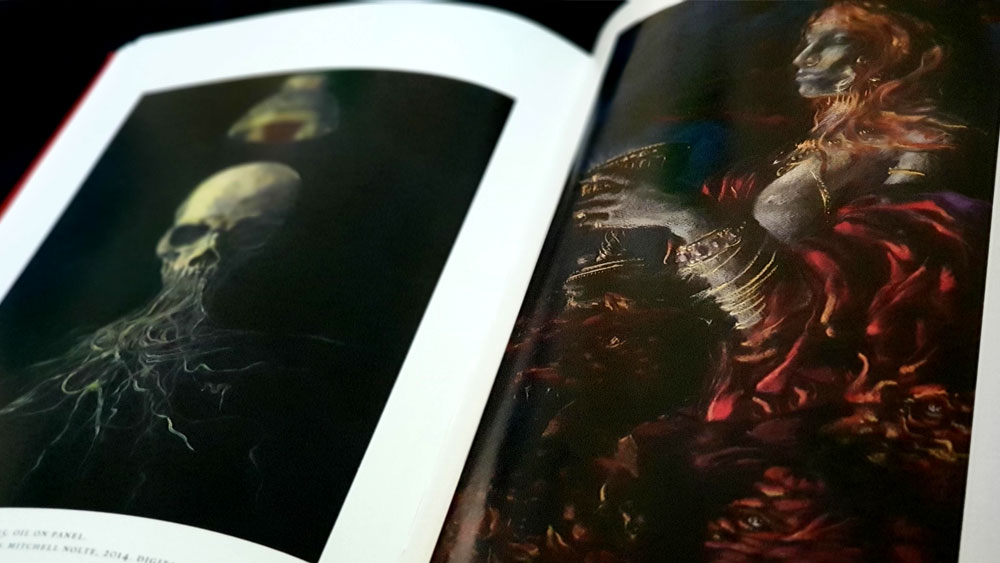

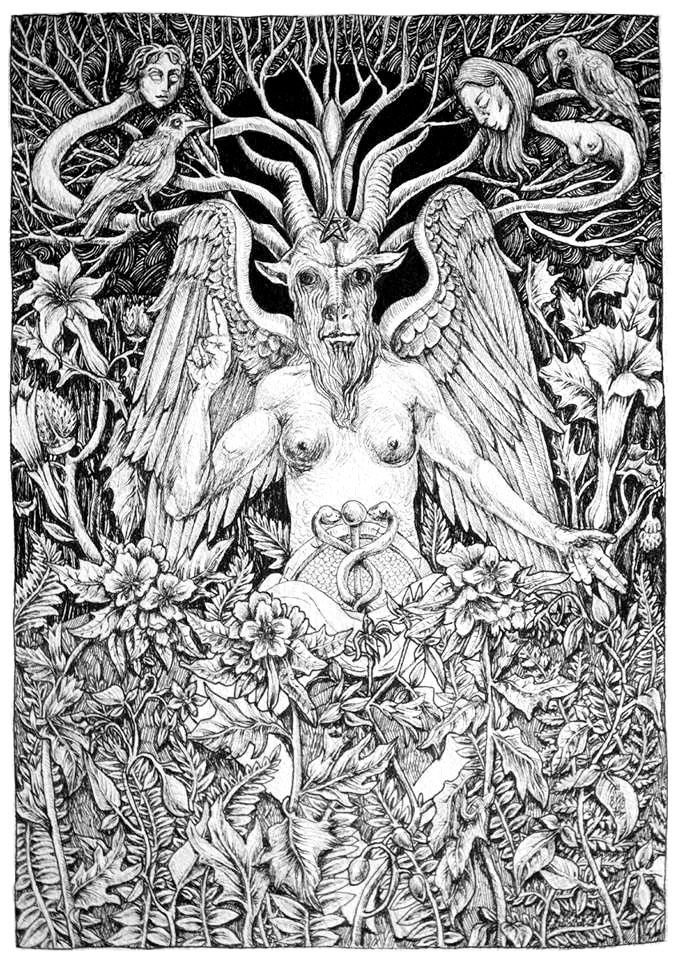

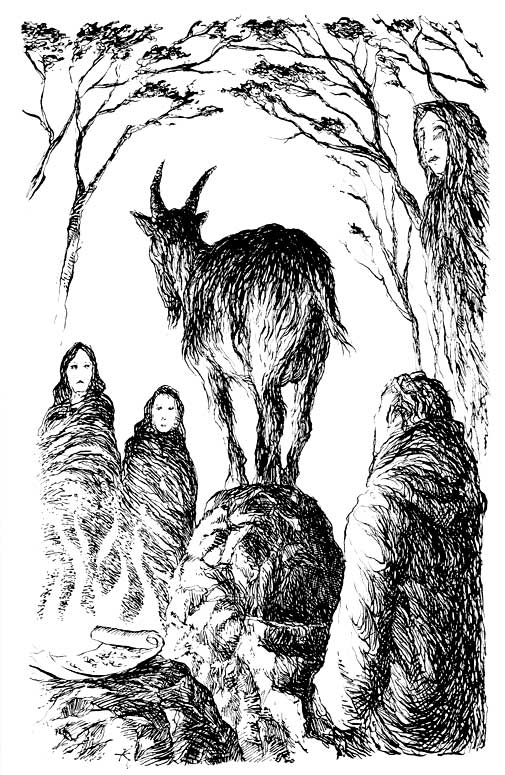

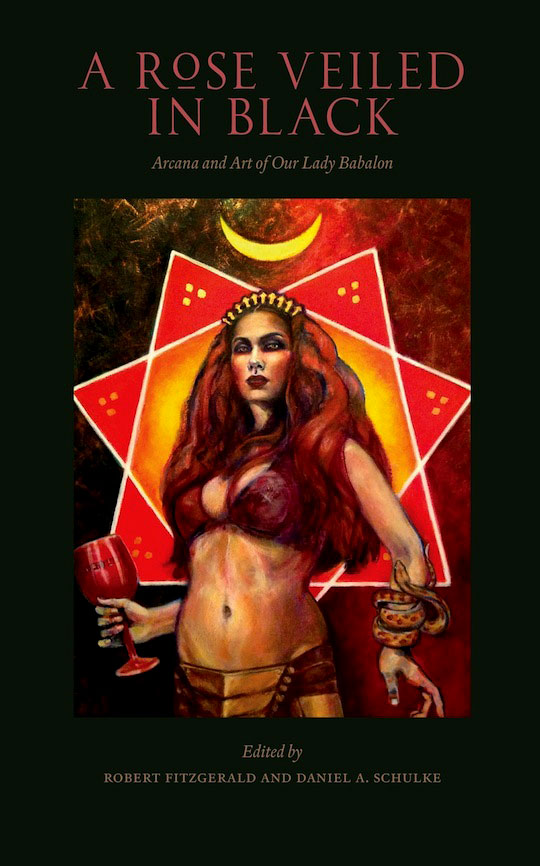

A smattering of black and white images are scattered throughout A Rose Veiled in Black (with some Babalon henna designs by Nicole DiMucci Potts providing a consistent but atypical interstitial style), but the bulk of visual contributions are found as full colour plates in the centre of the book. These are all, suitably, quite luxurious, with the most notable examples being ones in which oils, acrylics and their digital approximates, render Babalon in swathes of fleshy brushstrokes. Mitchell Nolte’s digital Our Lady Babalon has her bare-breasted and enthroned within a dense tableaux that has something of Gustave Moreau’s regal, decadent splendour about it. Timo Ketola’s pastels on paper Babalon carries a similar feeling of opulence with libidinous folds of cloth cascading from a chalice-wielding Babalon. The chalice reappears in Linda Macfarlane’s Babalon, where she stands strong before an acrylic-rendered septagram, her hair a Kate Pierson-like mane of red and her left arm snake-entwined. Finally of note is Liv Rainey-Smith’s 2014 woodcut with hand-applied garnet, purpurite, tigers eye, bloodstone and jade in which Babalon most closely resembles her apocalyptic description, riding upon the seven-headed beast and carrying the cup of her fornications in her hand.

Layout is expertly handled by Joseph Uccello in a functional serif for body and subheadings. The only flash of glamour comes from the titles, which are rendered in Moyenage 32, a blackletter face with a hint of the modern, which feels strangely fitting here without falling into the trap of being obviously Babalonesque (neither overly ‘occult’ or stereotypically ‘feminine’).

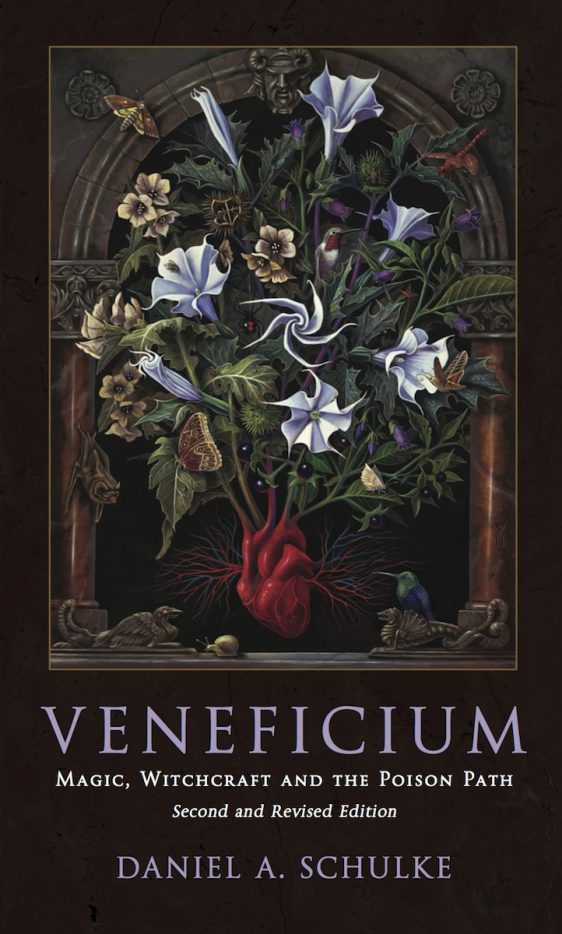

A Rose Veiled in Black was made available in two editions: a standard hardcover edition with a dust jacket, limited to 1,092 copies, and a deluxe edition of 77 copies, quarter-bound in scarlet goat with marbled papers. The standard edition is bound in red cloth with text foiled in gold on the spine, while the dust jacket bears the image of Babalon by painter Linda Macfarlane, who has previously explored a number of other Babalonian themes.

Published by Three Hands Press