After their first forays into occult publishing with the Pillars journal, Anathema Publishing presented their first stand-alone title with Crafting the Arte of Tradition by Shani Oates. Since then, at the time of writing, they have followed this up with two books by Craig Williams, one by Anathema owner Gabriel McCaughry, and two further titles from Oates. With an expanded paperback edition of Crafting the Arte of Tradition now available from Anathema, let’s get a review of the classic hardback original from 2016. Full disclosure time, I have had pieces published by Anathema Publishing in the past, and have worked for them as a copy editor. Will this have an effect on this review? Let’s find out.

After their first forays into occult publishing with the Pillars journal, Anathema Publishing presented their first stand-alone title with Crafting the Arte of Tradition by Shani Oates. Since then, at the time of writing, they have followed this up with two books by Craig Williams, one by Anathema owner Gabriel McCaughry, and two further titles from Oates. With an expanded paperback edition of Crafting the Arte of Tradition now available from Anathema, let’s get a review of the classic hardback original from 2016. Full disclosure time, I have had pieces published by Anathema Publishing in the past, and have worked for them as a copy editor. Will this have an effect on this review? Let’s find out.

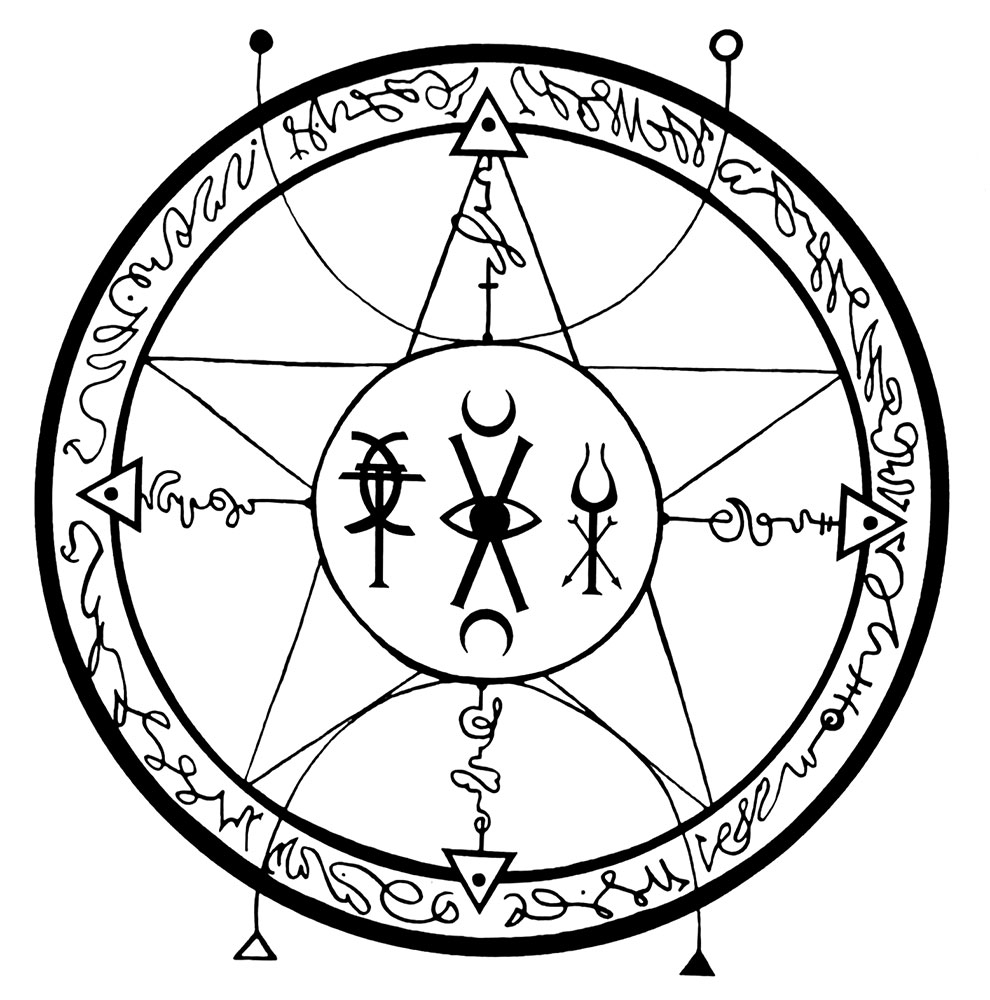

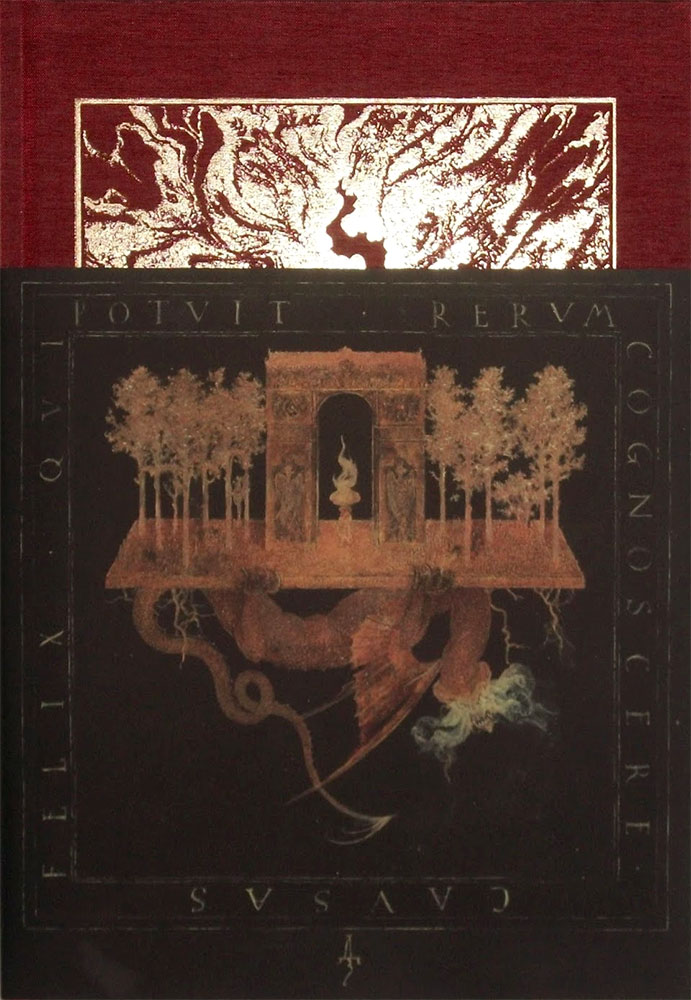

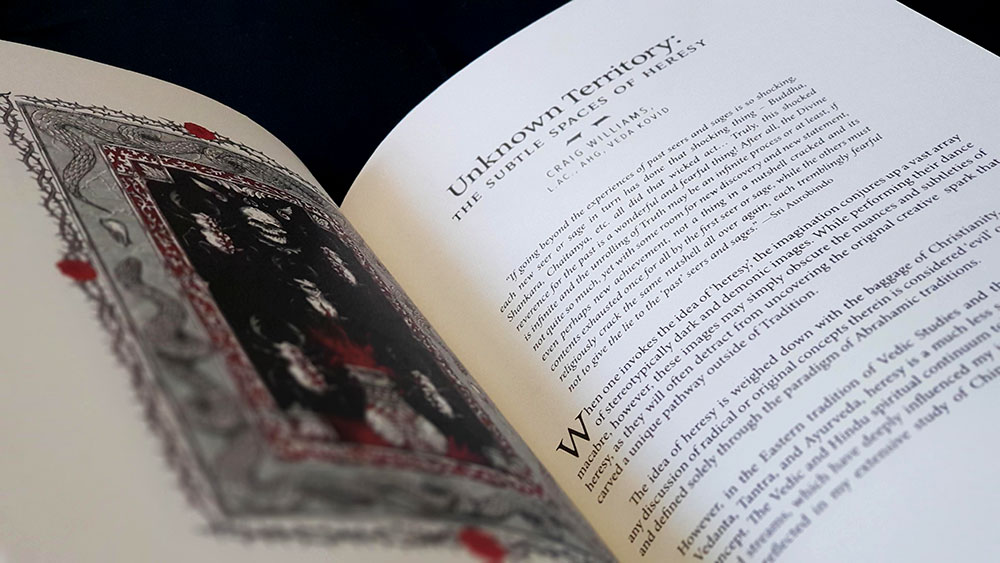

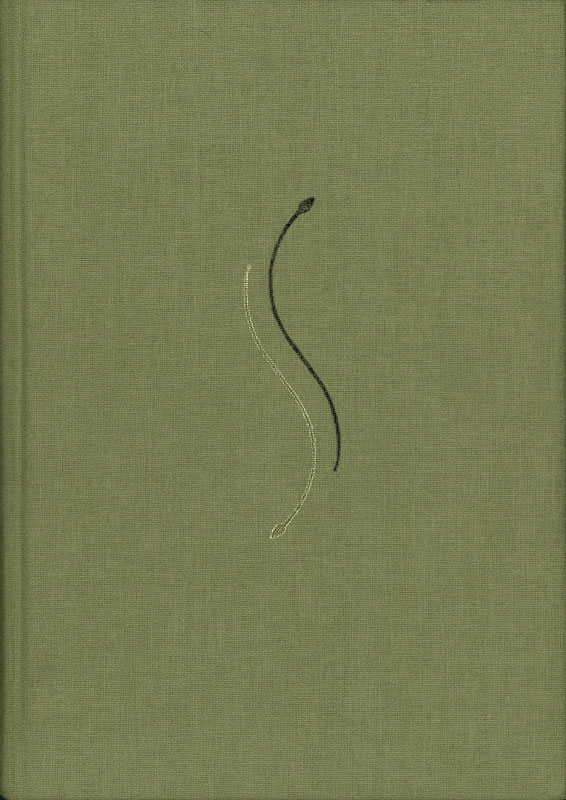

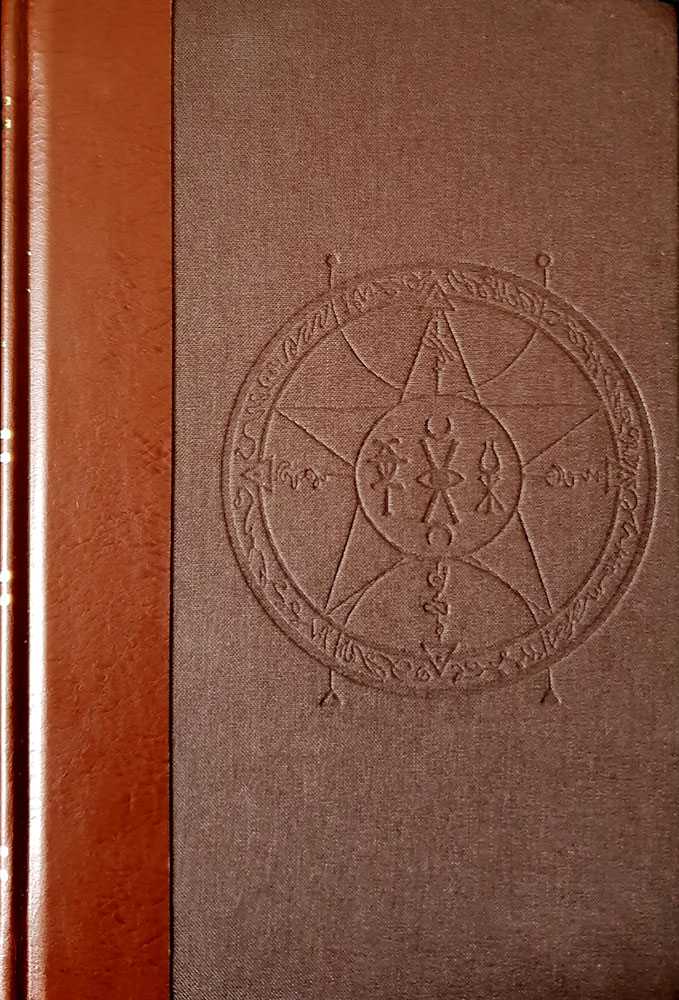

Normally the reviews here at Scriptus Recensera leave the discussion of the book’s appearance to the end, but let’s switch that up and start off by judging this book by its cover. It’s beautiful. Brown where many occult publishers go black, Crafting the Arte of Tradition has a confident appearance, with a sigil blind debossed into the cloth cover, and the title and author in gilt on the spine creating a contrast with the russet tone. Inside the cover, the beauty continues, as McCaughry displays a deft and sophisticated hand when it comes to typography, with chapter titles simply but effectively rendered in a combination of different styles and cases; though I’m not sure what I think about the use of the attractive and meaningless pilcrow (¶) in subtitles. That said, the margins are a little snug, and with the full justification of type, this creates somewhat intimidating blocks of typographic colour that fill the pages; something that appears to have been rectified in the new paperback edition.

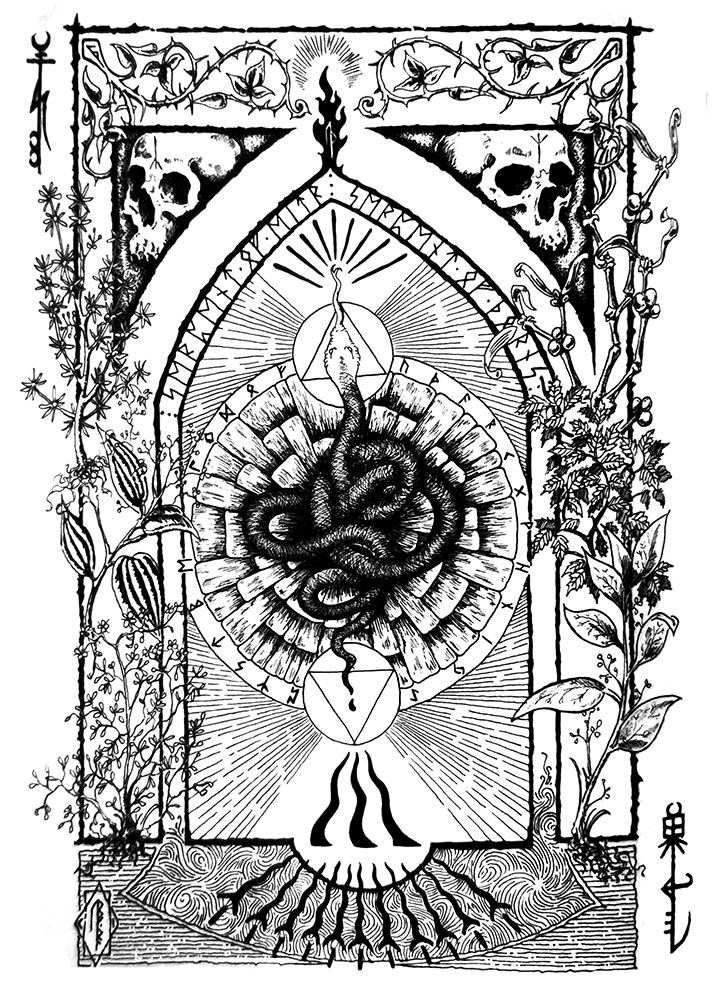

Images throughout Crafting the Arte of Tradition are used sparingly and effectively, with Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos providing starkly beautiful line drawings as both full page illustrations and as fillers and end pieces. These are unashamedly indebted to Aubrey Beardsley, but Vasconcelos makes the style her own, adding innovation rather than relying on slavish imitation. Her forms have a regal, Marjorie Cameron-style elegance, arrayed in fantastical costumes and robes, sprinkled with just the right touch of distance and distain.

As for the written content, Crafting the Arte of Tradition is very much Oates to a T. She obviously loves to write, though sometimes without consideration for the reader: brevity is sacrificed on the altar of verbosity, and paragraphs run long, stretching to as much as half a page in some cases. Oates seems to have studied at the same writing school attended by Andrew Chumbley and Daniel Schulke, or at least taken a postgraduate paper there, as her writing, which has been straight forward enough in the past, is unnecessarily ornamented and tortuous.

Crafting the Arte of Tradition is arguably part of a recent trend towards a more, how you say, philosophical or analytical approach to witchcraft, instead of the tired rituals-n-recipes formula that has dominated that branch of occult publishing for over fifty years. Peter Grey’s Apocalyptic Witchcraft provided a precedent for this (though his approach is more poetic than academic), while The Witching-Other: Explorations & Meditations on the Existential Witch by Peter Hamilton-Giles is a more recent example. What that means in reality, though, can be that simple concepts are given an unnecessary veneer of complexity due to the use of repetition, and the employing of language that obfuscates, rather than reveals.

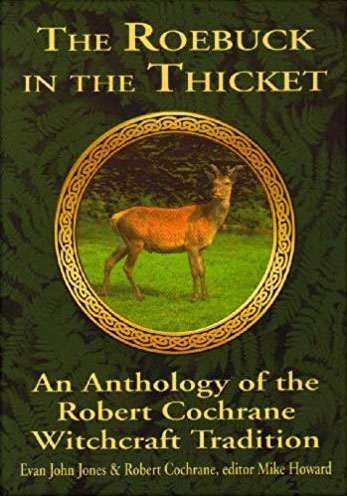

Despite being ostensibly an explication of the craft as viewed by Robert Cochrane’s Clan of Tubal Cain, it’s sometimes easy to forget this as for the first couple of chapters, one finds oneself lost in an Oatesian swirl, within which it can be hard to understand or determine a particular focus. This is not just because of Oates’ obtuse language, but the structure, wherein there is often no flow, and paragraphs can begin abruptly as non sequiturs, as if you dozed off a little and have been rudely jolted awake. It is not that the words are obscure or archaic, which they aren’t, but that the phrasing that ties them together is clumsy and circuitous, with tenses changing, and flow halting, overwhelmed by the attempt to sound grander, more authoritative or more arcane than is needed. Improper use of commas plays a large part here, with that little flick being often poorly and inexplicably placed, making for an even more difficult read, and for one in which the immersion for the reader is constantly being broken as you go “What? That’s not how commas work.” The most generous assessment would be to call this writing a stream of consciousness, with all its abrupt leaps and sentence fragments, but even then, a little wrangling of words would have done wonders to instil some sense of, well, sense.

This lack of comprehensibility is compounded by sloppy proofing and referencing where stray or repeated words litter sentences, and where in some cases, sources have been cut and pasted and then not edited for accuracy. In one particularly egregious example, what is clearly an OCRed source text is quoted, but has been so inattentively dealt with that two errors introduced in the text recognition process occur in its single sentence length: ‘the’ has been scanned and left as ‘I lie,’ while a salt pit called the Old Biat is instead referred to ‘Old Bin I.’ As it is, this quote is incorrectly attributed and cited. It is not, as is unhelpfully and vaguely claimed, from “an historian by the name of Nash” but from The History of the County Palatine of Chester by J. H. Hanshall. The reference to Nash comes from the secondary source used by Oates (A Glossary: Or, Collection of Words, Phrases, Names, and Allusions to Customs, Proverbs, &c., which Have Been Thought to Require Illustration, in the Works of English Authors, Particularly Shakespeare, and His Contemporaries by Robert Nares) which quotes both Nash (that would be Dr Treadway Russell Nash, 1724 – 1811, for those keeping score at home) and Hanshall in the same section, but in relation to clearly different facts. The title of Hanshall’s work, but not Hanshall himself, is then cited by Oates as the source, despite having just claimed that this statement is by “an historian by the name of Nash… famous for his summation of the festival,” with the source and page numbering clearly just being lifted from Nares’ referencing of Hanshall. The same citing of a secondary source as if ‘twere a first occurs in the following paragraph where Oates again uses the entry from Nares’ book in quoting from “another historian named Lysons” (that would be the Reverend Daniel Lysons in his Magna Britannia: Being a Concise Topographical Account of the Several Counties of Great Britain. Containing Cambridgeshire, and the County Palatine of Chester, Volume 2 from 1810). This source is duly cited by cutting and pasting the truncated, authorless-citation format employed by Hanshall, rather than going looking for the original publication by the Reverend Lysons.

The above is highlighted in excruciating detail not to score points or to shame, but out of disappointment. When a lot of effort has gone into a book like this, as the glowing first half of this review is testament to, it is a shame when poor scholarship comes through like that in such a pellucid manner; especially when the resources are available to so easily get it right (all three books are available on Google Books and are fully searchable). When one is presenting a tradition and using historical documents to back up its themes, surely accuracy matters, especially when weak work in one area can make the reader wary of the rest. And speaking of references, for whatever reason Cochrane is referred to throughout this book with his birth name of Roy Bowers, which means that when his articles are referenced, they’re now nonsensically cited as the work of one Mr Bowers, when that isn’t the name under which they were published.

It is only in later chapters of Crafting the Arte of Tradition that clear points, albeit laboured, rather than well made, can be discerned, and that’s possibly only because it’s broken up by clear subtitles that indicate the subject area. Here, Oates discusses various tools of the craft, locations of power and various other symbols from folklore, myth and legend, but there’s still an unavoidable sense of aimlessness, with no clear direction and with the various thematic locales wandered into as if by accident.

So in summary, come for the prettiness, wade through the wooliness. Crafting the Arte of Tradition is presented as a 200 page hardcover octavo with gilt lettered bonded leather spine, matching blind stamped cloth boards, metallic endpapers, colour and black and white illustrations, and appendices. It is limited to 300 copies of which 280 are bound as the standard edition; the remaining twenty comprise the Fjölkunnig special edition and are bound in full leather, instead of cloth boards. In the hand, Crafting the Arte of Tradition feels very solid with its leather binding, brown cloth and the slightly heavier than usual weight of the pages within.

Published by Anathema Publishing