Originally published in 2012 by Lear Books with the seemingly more fitting subtitle of The Nature of Historic Witchcraft in Great Britain, Operative Witchcraft is a relatively broad consideration of British witchcraft, distinguishing it from other titles in Pennick’s oeuvre which often have a more regional focus. As detailed by the back-cover blurb, this is a journey through operative witchcraft in the British Isles, beginning in the Middle Ages, continuing into the Elizabethan era and up to the modern period with its decriminalisation in the 1950s and through to the present.

Originally published in 2012 by Lear Books with the seemingly more fitting subtitle of The Nature of Historic Witchcraft in Great Britain, Operative Witchcraft is a relatively broad consideration of British witchcraft, distinguishing it from other titles in Pennick’s oeuvre which often have a more regional focus. As detailed by the back-cover blurb, this is a journey through operative witchcraft in the British Isles, beginning in the Middle Ages, continuing into the Elizabethan era and up to the modern period with its decriminalisation in the 1950s and through to the present.

Originally published in 2012 by Lear Books with the seemingly more fitting subtitle of The Nature of Historic Witchcraft in Great Britain, Operative Witchcraft is a relatively broad consideration of British witchcraft, distinguishing it from other titles in Pennick’s oeuvre which often have a more regional focus. As detailed by the back-cover blurb, this is a presented as a journey through operative witchcraft in the British Isles, beginning in the Middle Ages, continuing into the Elizabethan era and up to the modern period with its decriminalisation in the 1950s and through to the present.

Despite the clarity of this brief, Operative Witchcraft seems to take a while to figure out the kind of book it wants to be, and to determine the direction it wants to take. The first couple of brief chapters consider, in a somewhat abrupt manner, various aspects of witchcraft, with particular emphasis on folklore and the power and perception of the witch within communities. While Pennick’s editorial voice is clear from the start, having that world-weary assuredness of someone who has been writing and rewriting about this stuff for decades, it gets lost in some of the early chapters when it is swamped in data dumps that are awkwardly tied together; a complaint I have made recently about other witchcraft books but never before had to make with Pennick. Information often feels like notes, anecdotes and points of interest that haven’t properly been integrated into the greater narrative, often being introduced as disorientating non sequiturs with no preamble to provide context. And then there are short sentences and weird asides that perhaps an editor could have excised for conciseness, like when mid-paragraph in a discussion of toad folklore and magic, Pennick says that it is interesting that in Cockney rhyming slang ‘frog and toad’ means ‘road,’ but no, it really is not. It’s not interesting at all, in any relevant sense of the word.

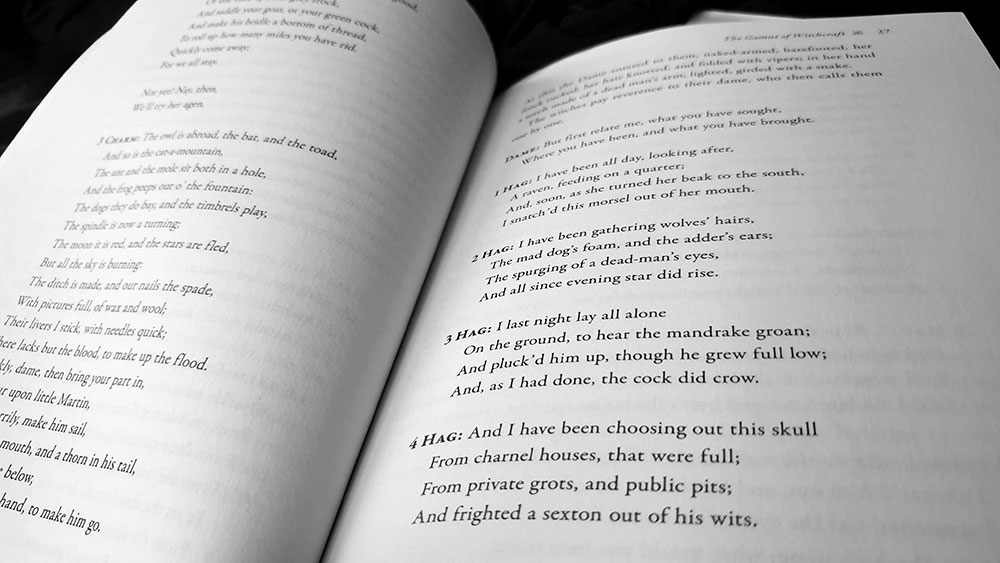

The fourth chapter takes a different but equally discombobulatory approach from its predecessors and devotes its entire length, save for a two page preamble, to reprinting an excerpt from Ben Johnson’s 1609 The Masque of Queens. While this is an intriguing example of fiction infused with then extant knowledge of witchcraft practice, the excerpt is presented and then just left, with the chapter ending with no analysis, no comment, save for one note about the crane fly mentioned in the text. Yes, any reader with some familiarity with the themes of occultism can make their own assessment and unpacking of Johnson’s picturesque and symbolically rich text, but that doesn’t make it any less jarring to find it presented like an incongruous novelty, page filler or a misplaced appendix, devoid of editorial insight.

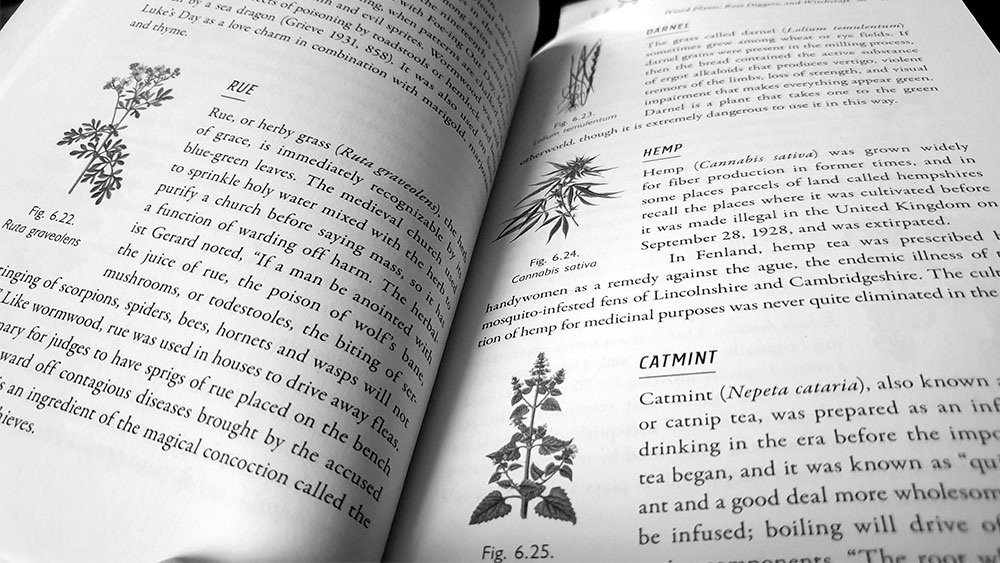

The tone shifts again with the following chapter’s consideration of witchcraft and the legal system, which, as interesting as it is, still seems a pivot in its well-referenced deep dive into legal rulings and parliamentary acts. This is especially so when the next chapter surprisingly turns almost practical in a discussion of root work and plant magic, providing the reader with an exhaustive herbal of 26 witchcraft-associated plants. Each entry gives a brief outline of the plant’s history and its folkloric usage, accompanied by public domain or Creative Commons images, all well reproduced and to a casual glance, relatively consistent in style.

Pennick’s remaining chapters consider a few specialist areas of witchcraft folklore and practice, though by no means all of them, and in so doing, there’s a feeling of things being treated somewhat disproportionately. For example, ten pages are devoted to the rather well-travelled theme of frog and toad magic, and another on places of power, while a whole slew of other things are bundled under the rubric of ‘witchcraft paraphernalia,’ and then, other than brief chapters on Obeah and the emergence of Wicca, there’s not much else.

This all contributes to the unfocussed and piecemeal feeling of Operative Witchcraft, where one could imagine that the book is made up of separate, previously published articles, all stitched together, rather than created from whole cloth; hence that prevailing sensation of casting about trying to find a direction for the whole book. It’s not that Operative Witchcraft needs to be a definitive account of British witchcraft, goddess knows there are enough of those out there covering the same well-worn ground, it’s just that sometimes it seems to want to be that, and then at other times, it doesn’t.

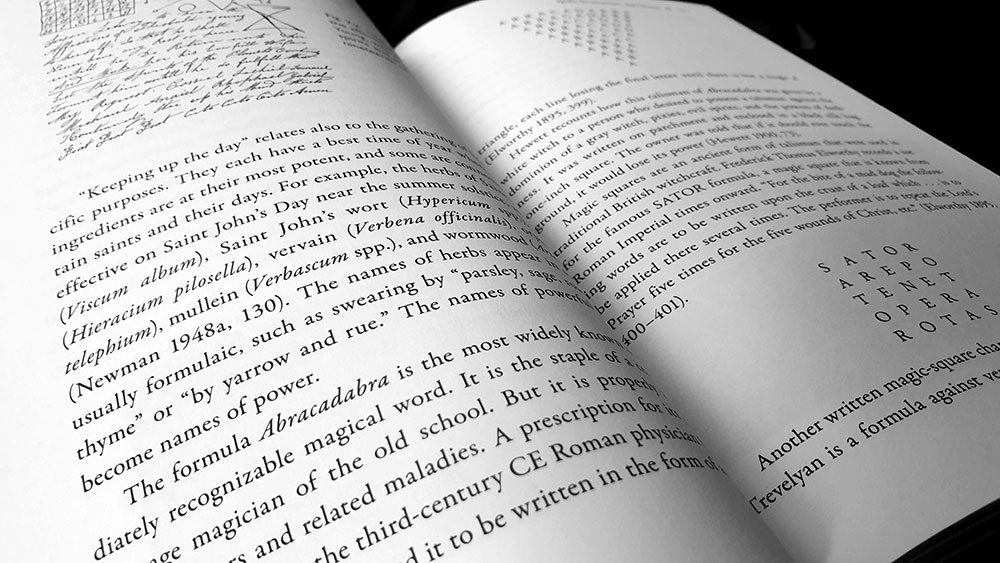

Pennick cites his material thoroughly throughout, using in-body citations that link to a 24 page reference section at the rear, so there’s certainly a cornucopia of information contained within these pages, it’s just not presented in the most sympathetic manner. The layout of Operative Witchcraft is by the ever-reliable Debbie Glogover, with the body set in Garamond and chapter headings in the slightly slab-seriffy Rockeby Semiserif, with subheadings in Rotis Semi Serif and Gill Sans. Illustrations and photographs dot the pages, providing consistent visual interest, all high quality and well produced, as one would hope.

Published by Destiny Books/Inner Traditions