With its blockbuster subtitle declaring The Return of the Great Beast, this sequel from Tobias Churton picks up where his previous work, Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin, left off; a title that was in itself a sequel to his other books documenting Crowley’s time in America and India respectively. Given the chronology surveyed in the previous titles, we are safe in assuming that the ‘in England’ here does not refer to Crowley’s time spent in England for the majority of his life but rather his return there for his final fifteen years from 1932 to 1947. In doing so, Churton is able to conclude his multiple volume biography of Crowley and focus on a period that is relatively little explored, but which shows that the near penniless Great Beast still got a lot done, even if it was only cooking a lot of curries, and being on the perpetual scrounge in both the actual and the astral.

With its blockbuster subtitle declaring The Return of the Great Beast, this sequel from Tobias Churton picks up where his previous work, Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin, left off; a title that was in itself a sequel to his other books documenting Crowley’s time in America and India respectively. Given the chronology surveyed in the previous titles, we are safe in assuming that the ‘in England’ here does not refer to Crowley’s time spent in England for the majority of his life but rather his return there for his final fifteen years from 1932 to 1947. In doing so, Churton is able to conclude his multiple volume biography of Crowley and focus on a period that is relatively little explored, but which shows that the near penniless Great Beast still got a lot done, even if it was only cooking a lot of curries, and being on the perpetual scrounge in both the actual and the astral.

Churton has a brisk style of writing that combined with the type’s large point size, and the surfeit of images, propels the reader forward at quite a pace. Enabling this still further is that some of what is presented here are fleshed out diary entries, or details from letters, with little room for editorialising or much in the way of elaboration: Crowley had lunch with someone, he moved lodgings, he wrote a letter to such and such, he did a sex magic operation for money, and he carped about the Agape Lodge in California (despite them doing a damn sight more for Thelema than he was). This brevity isn’t necessarily a criticism, merely a comment on how the narrative contains much that is minutiae, with little padding added beyond what has been left by Crowley’s own hand. This ably conveys the intricacies, and frequent mundanities, of Crowley’s everyday life, even if said moments are not necessarily all that detailed, and with each entry moving us rapidly through the months.

With that said, there are moments where the piecemeal nature of some of the sections may have gotten the better of either the narrative, such as it is, or the editor and layout designer, with abrupt sentences descending into a unintelligible mess of uncertain intent. Sometimes a sentence needs to be read several times before its intent is clear, not because of any complexity but rather due to its economy, with so little to be gleaned from a minor concatenation of words. There are other strange moments, such as a section from pages 28-30 describing the content of three letters, which begins abruptly with two non sequitur, single-sentence paragraphs, one from October 1993 and the other from the more recent “some years ago.” The more recent event is the sale by Weiser Antiquarian of the letters decades after they were written, but by leading with the description of the letters’ sale, rather than the context in which they were written, the reader becomes discombobulated by this jumping forward in time. In a similar manner, the narrative of Crowley’s day to day and current events is temporally upended on page 80 when a one-sentence paragraph noting that the Buchenwald concentration camp was opened in 1937 is followed by one that begins by describing how the LAShTAL Aleister Crowley Society website reported in 2011 of the sale of a letter written by Crowley on Piccadilly Hotel stationery, momentarily making it feel like the two events were relatively concurrent. It’s all very confusing, as if notes and scraps have been cut and pasted and never fully massaged into tense-correct shape.

Whilst we’re being critical, there are other little quirks that tend to grate, most notably where it appears that having to constantly refer to Crowley by name got tiresome, and as a result, sometimes, out of nowhere, he can be variously referred to as 666, Therion, and most startling in its incongruity, Baphomet. While most readers will be aware of Crowley’s proclivity for pseudonyms and titles, it’s not clear why it stops there. Why not call him Perdurabo, Ankh-f-n-khonsu, Mahatma Guru Sri Paramahansa Shivaji or a little sunshine as well?

Inevitably, comparisons must be made to other books that cover the same period of Crowley’s life, with the obvious one being Richard Kaczynski’s definitive Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley. Kaczynski has a greater narrative sense, an authorial overview that makes for easier reading, and as a result, there’s a lot less of the jarring little events and piecemeal nature seen here. What Churton’s work does have going for it is the sense of immediacy, with the diary-like quality creating a somewhat intimate insight into Crowley’s day to day life and allowing the reader to see what an unpleasant, arrogant, irascible and ultimately exhausting scoundrel he must have been to interact with personally. Also, it must be said that Crowley’s constant attempts to get the war-time British government to employ him as an adviser or expert come across as sad, especially with the way in which his consternation was palpable after each time a long-suffering bureaucrat declined his offer.

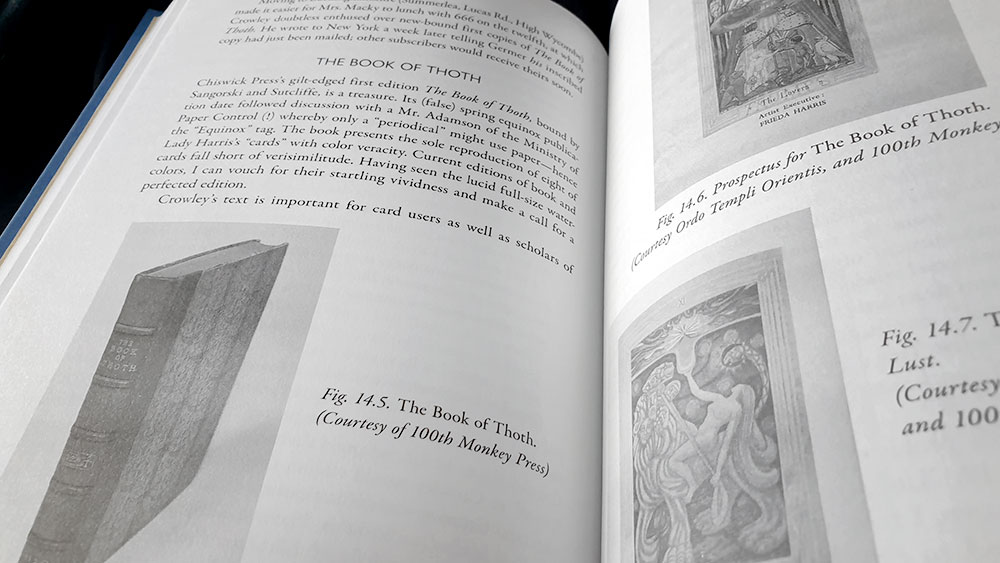

Despite this emphasis of the smaller aspects of Crowley’s life, this period did include some significant magickal outputs, and Churton spends a great amount of time documenting the creation of the Thoth tarot deck in collaboration with Lady Frieda Harris. All events in the process, from Crowley’s first introduction to Harris up to the tarot’s completion and publication, are covered, taking the reader on a comparable journey to its creators. It’s moments like this that show the worth of Aleister Crowley in England, with its fairly well illustrated survey of the tarot and its evolution, indicative of one of the benefits of this title as something one can dip into for the details, without having to read a longer narrative.

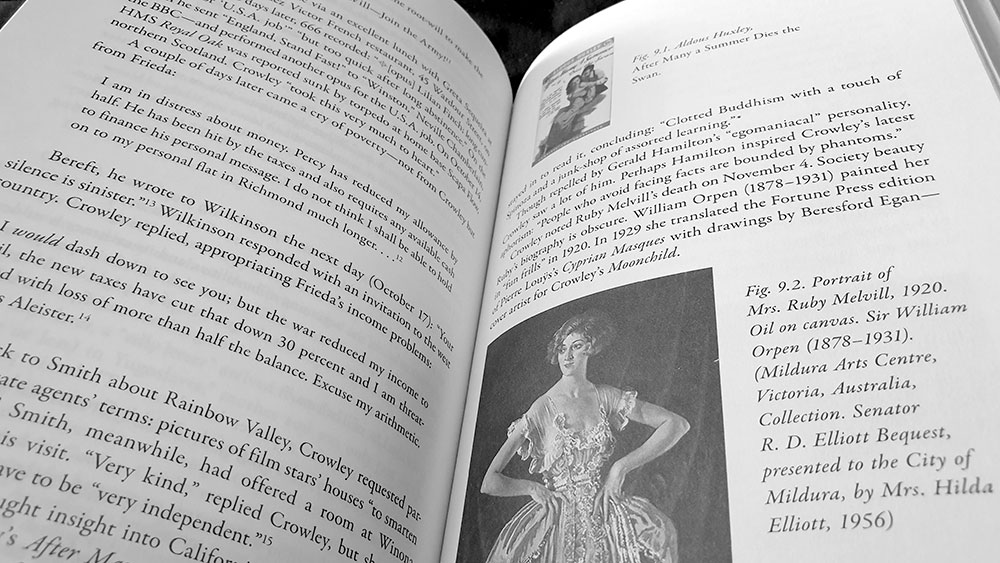

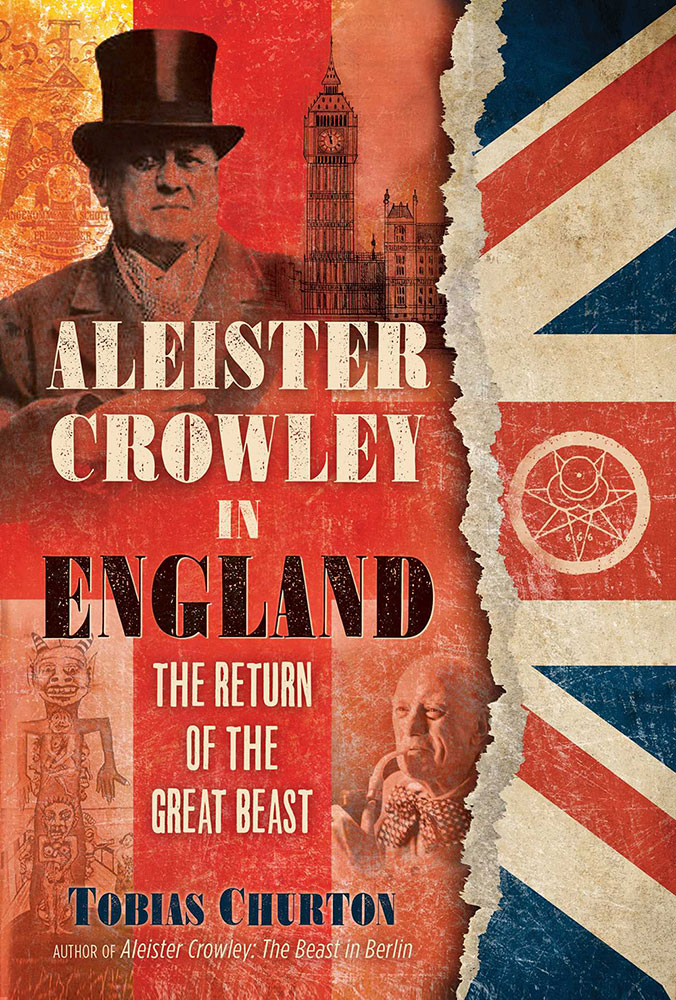

Aleister Crowley in England is presented as a hardback edition, bound in blue beneath a dustjacket with a rather fetching photographic montage design by Aaron Davis, with Union Jack and all, just so you know it takes place in England. Typesetting by Debbie Glogover uses Garamond for body copy with titles in Gotham Condensed, and other display text in a combination of the stoic sans serifs Gill Sans, and Legacy Sans. Photographs are used profusely throughout, though their presence can seem disproportionate and arbitrary, such as when someone who receives only a single passing mention is rewarded with a portrait, while more significant figures have none.

Published by Inner Traditions