In 2002, Strandagaldur, also known as the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft in Hólmavík, Iceland, hosted the Exhibition of Sorcery and Witchcraft, which one assumes evolved into or contributed to the museum’s permanent exhibition. Shortly after the opening it became evident that there was a need for a short book on Icelandic sorcery and witchcraft, one that reflected the questions asked of museum staff by visitors Icelandic and foreign; especially given the dearth of texts on the subject outside of academia. Angurgapi: The Witch-hunts in Iceland is exactly that. It is by no means a survey of the museum’s collection, for which there is now a catalogue, and instead gives a pithy and concise survey of Icelandic witchcraft, using the framing device of witch-hunts to delve a little deeper in places.

In 2002, Strandagaldur, also known as the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft in Hólmavík, Iceland, hosted the Exhibition of Sorcery and Witchcraft, which one assumes evolved into or contributed to the museum’s permanent exhibition. Shortly after the opening it became evident that there was a need for a short book on Icelandic sorcery and witchcraft, one that reflected the questions asked of museum staff by visitors Icelandic and foreign; especially given the dearth of texts on the subject outside of academia. Angurgapi: The Witch-hunts in Iceland is exactly that. It is by no means a survey of the museum’s collection, for which there is now a catalogue, and instead gives a pithy and concise survey of Icelandic witchcraft, using the framing device of witch-hunts to delve a little deeper in places.

It is, though, the witch-hunts in Iceland that the book devotes much of its space to, beginning with a summary of several notable early cases. What immediately becomes clear is that contrary to the continental stereotype, it was men who received the most convictions for sorcery in Iceland, and not just any men but men of the cloth. In many cases, accusations of witchcraft seems to have gone hand in hand with clerical infidelity, with Rafnsson presenting several examples of priests who were accused of witchcraft as well as fathering children or engaging in adultery or sexual assault. Even Gottskálk Nikulásson, the last Catholic Bishop of Hólar from 1496 to 1520 (who had multiple mistresses and sired at least three children), was thought to be a sorcerer, and the author of an infamous grimoire called Rauðskinna.

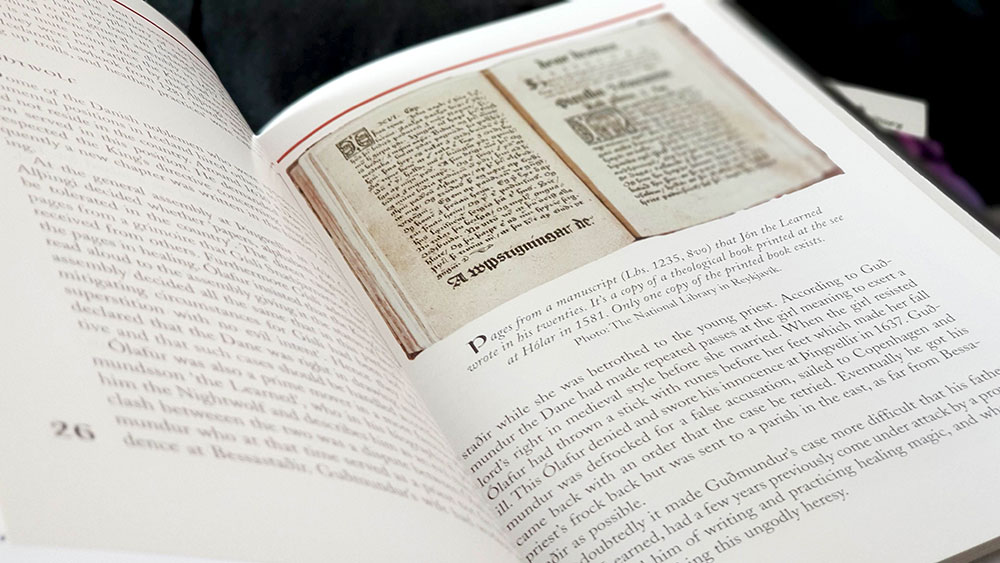

One exception to this template, indeed its polar opposite, was Jón Guðmundsson the Learned, who, as his name suggests, was something of a 16th-century Icelandic Renaissance man, being a writer, artist, sculptor, and an observer and documenter of nature. He ran afoul of the authorities when he criticised the murder of a group of Basque whalers in the Westfjords, and this ultimately led to accusations of witchcraft when a book he had written was used as evidence of diabolism. Jón admitted to writing the now lost volume and defended it as a book of healing without any evil purpose. While the image of Jón as a polymath with inclinations towards natural philosophy would seemingly make authorship of a grimoire unlikely, a listing of the book’s sections preserved in court documents reveals not herbal cures, but spells of the type found in other black books: charms against elves, madness and fire, or spells for providing victory in war or against storms at sea, amongst others.

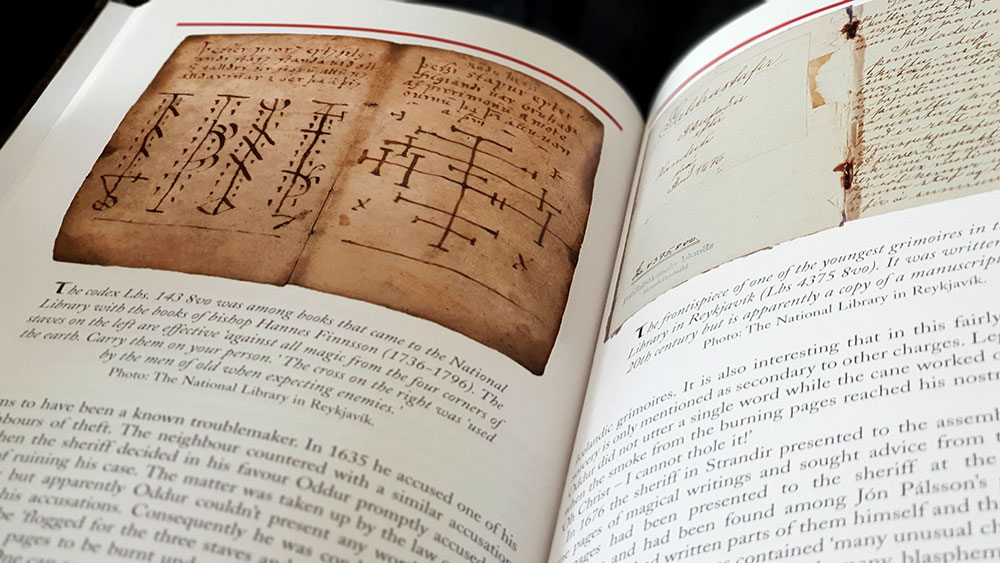

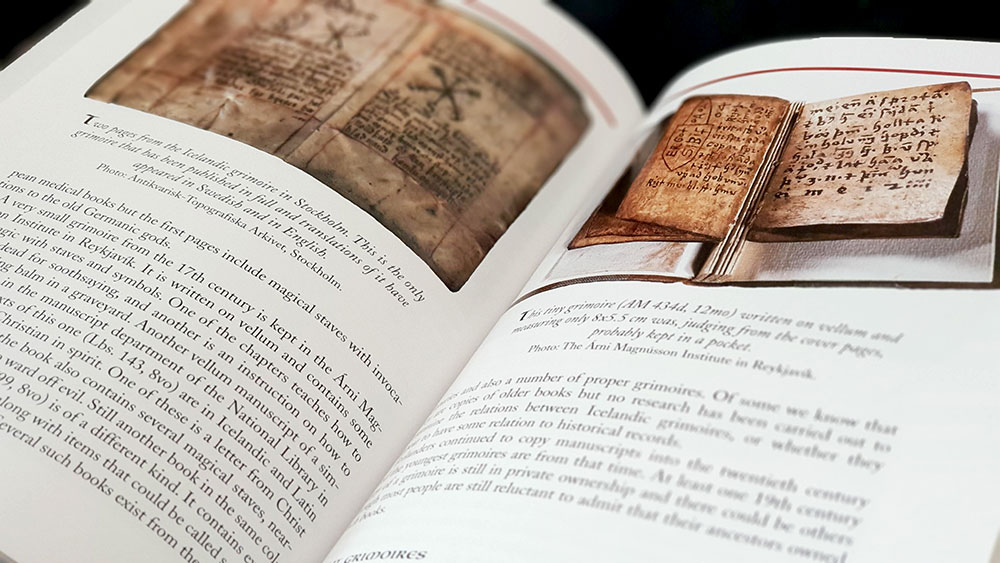

It is these types of grimoires and their attendant spells and charms that figure largely in the Icelandic accounts of witchcraft, rather than the transvection, sabbats and other diabolical congregations of their continental colleagues. As Rafnsson notes, almost a third of the Icelandic witchcraft trials centre on the possession of grimoires and other examples of rendered magical staves, charms or sigils. While many of these have been destroyed (with court records documenting two instances of a punishment in which the guilty party was made to inhale the smoke of the burning pages), what has survived presents various interesting themes: a juxtaposition in references to pagan and Christian deities, the combination of continental influences with entirely indigenous elements such as magical staves, and the role played by copying in transmitting this information down through the years.

What comes through clearly in the various accounts of witch trials is the sense of paranoia and fear prevalent at the time, where accusations of witchcraft often appear to be acts of self-preservation, where the accuser, even sheriffs and priests, could themselves easily become the accused. There is also a sense of disproportionate punishment, where admission of knowing and using a simple non-malicious charm could lead to exile or death. With some relief for the reader, Rafnsson does document the change in beliefs and values as society progressed, past cases were reassessed and found wanting (though small comfort to those who had been executed), and, as happened elsewhere, those who made accusations of witchcraft were increasingly more likely to be convicted for wasting the court’s time, rather than seeing their neighbours pilloried.

After a heart felt memoriam noting the loss of life and humiliation experienced by those accused of witchcraft, Angurgapi concludes with a little travelogue of the Icelandic witch-hunts, devoting four pages to various notable locations, each presented with a photo and a brief explanation. These help provide context to some of the accounts that have preceded it.

Rafnsson writes throughout Angurgapi in a clear, no-nonsense manner that is an effortless joy to read. Without much adornment, the facts are presented in a matter of fact but sympathetic manner that is surprisingly engaging. As such, Angurgapi achieves what it set out to do, providing a brief but by no means superficial survey of a topic for which there is still little thorough documentation of.

Angurgapi runs to a mere 85 pages but feels weightier due to the hardcover binding and wrap-around glossy cover (went a little overboard on the old Photoshop Texture filter there, folks). Inside, the pages are also glossy and colour images abound. These include beautiful scans of original manuscripts, principally spreads from grimoires, sourced from the National Library in Reykjavík. Text is formatted cleanly and confidently, albeit in nothing but humble Times, and there are little nice touches, like the overly large page numbers rendered in an uncial face. There is one reservation with the layout though, with the text alternating between three styling choices: body, block text and image captions. The block text, usually an addendum to something in the main text, are set in a grey box and styled at the same point size as the body, but with less, rather than more, of an indent. In some cases running to several pages long, they often awkwardly interrupt the main body and aren’t successfully identified as secondary in hierarchy. The same is true of image captions, which are rendered in an italicised face only a few point sizes smaller than the body, meaning that despite being centred and placed in relation to their respective image, the eye often reads them as if they are a continuation of the main text.

Since the release of Angurgapi in 2002, Strandagaldur have expanded their publishing, releasing the aforementioned catalogue, as well as various archival publications of grimoires: Tvær galdraskræður, a bilingual bringing together of two manuscripts, Lbs 2413 8vo and Lbs 764 8vo (aka Leyniletursskræðan); Lbs. 143,8vo (aka Galdrakver) as a two book boxset featuring a facsimile in one and translation in multiple languages in the other; and a complete facsimile edition of the galdrabók Rún with translation. All thoroughly recommended.

Published by Strandagaldur