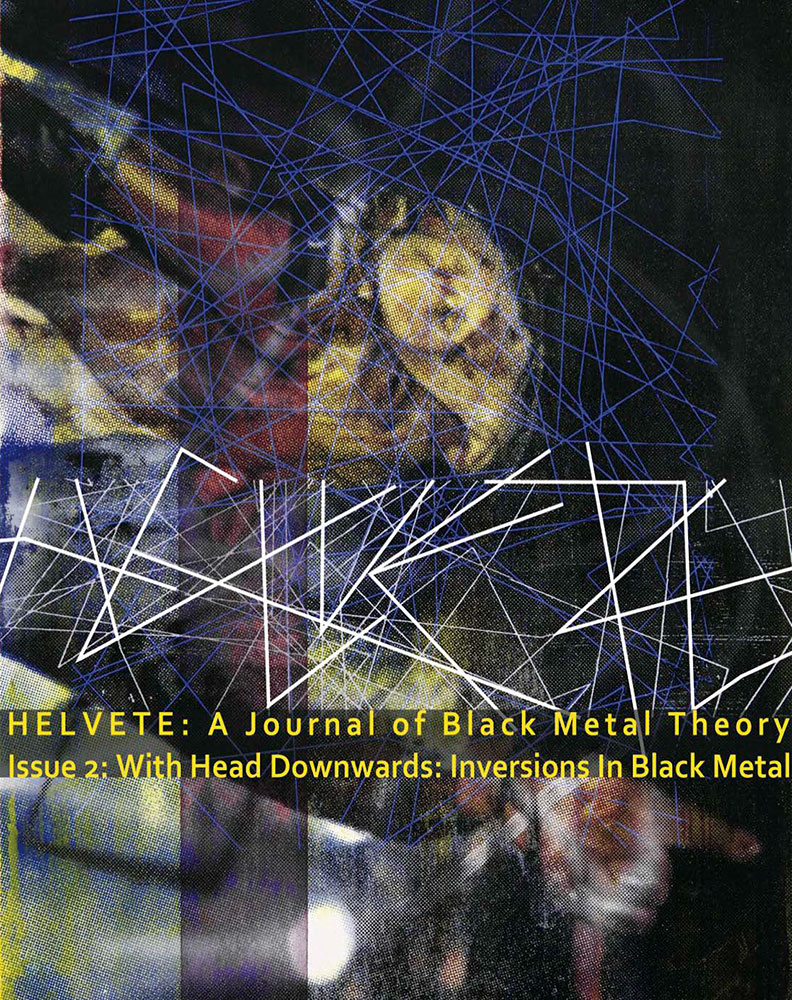

The first two volumes of Punctum Books’ Helvete journal have been previously reviewed here at Scriptus Recensera and 2016’s third instalment, edited this time by Amelia Ishmael, continues this often tangential consideration of black metal with a focus on the idea of black noise (and black metal as this black noise), thereby moving away from obvious touchstones to more outré realms. Written contributions come from Kyle McGee, Simon Pröll, Nathan Snaza, and Bert Stabler, while there are visual pieces from Alessandro Keegan, Bagus Jalang, Faith Coloccia, Max Kuiper, Michaël Sellam, the duo of Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert, and a combination of both written and visual by Susanne Pratt. As this line-up shows, there’s considerably more pictures than prose here, suggesting, perhaps, that there’s only so much theory one can write about black metal and that that limit may have been reached. But given this visual emphasis, let’s begin with the art side of things for once.

The first two volumes of Punctum Books’ Helvete journal have been previously reviewed here at Scriptus Recensera and 2016’s third instalment, edited this time by Amelia Ishmael, continues this often tangential consideration of black metal with a focus on the idea of black noise (and black metal as this black noise), thereby moving away from obvious touchstones to more outré realms. Written contributions come from Kyle McGee, Simon Pröll, Nathan Snaza, and Bert Stabler, while there are visual pieces from Alessandro Keegan, Bagus Jalang, Faith Coloccia, Max Kuiper, Michaël Sellam, the duo of Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert, and a combination of both written and visual by Susanne Pratt. As this line-up shows, there’s considerably more pictures than prose here, suggesting, perhaps, that there’s only so much theory one can write about black metal and that that limit may have been reached. But given this visual emphasis, let’s begin with the art side of things for once.

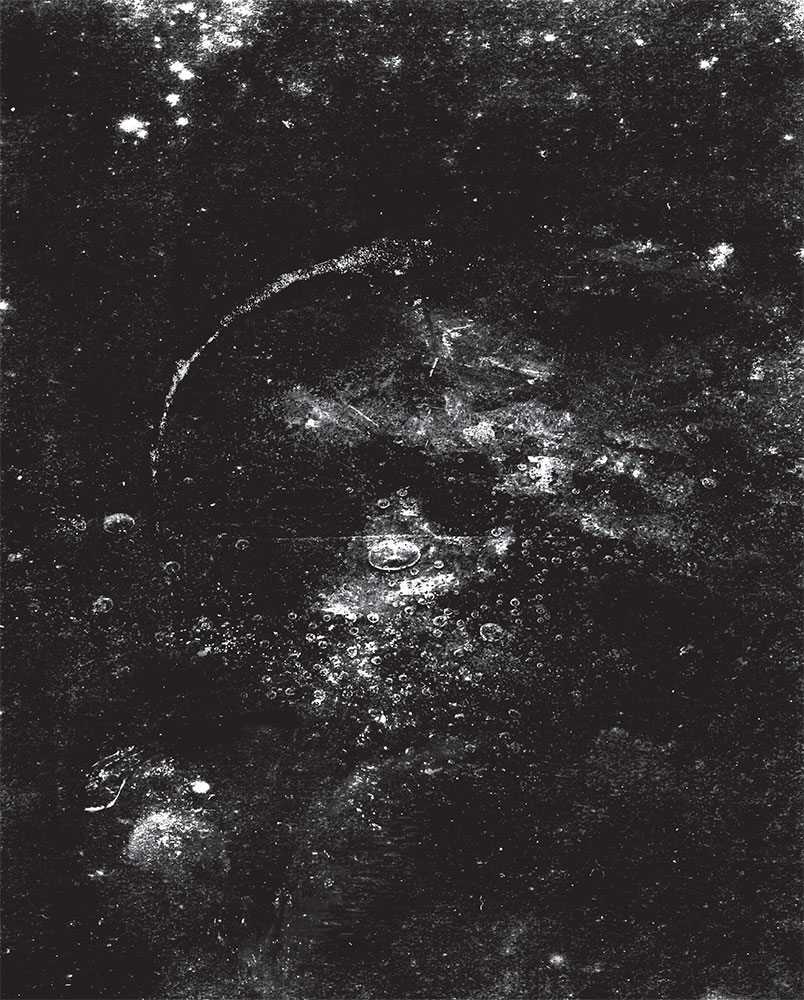

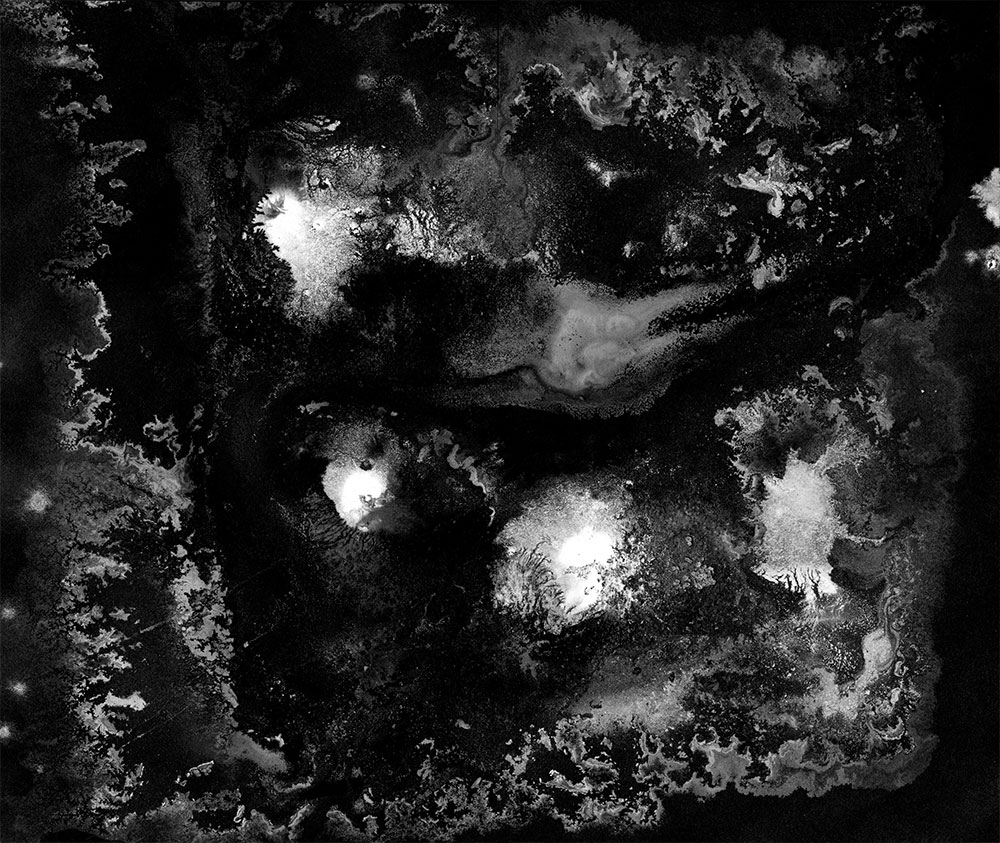

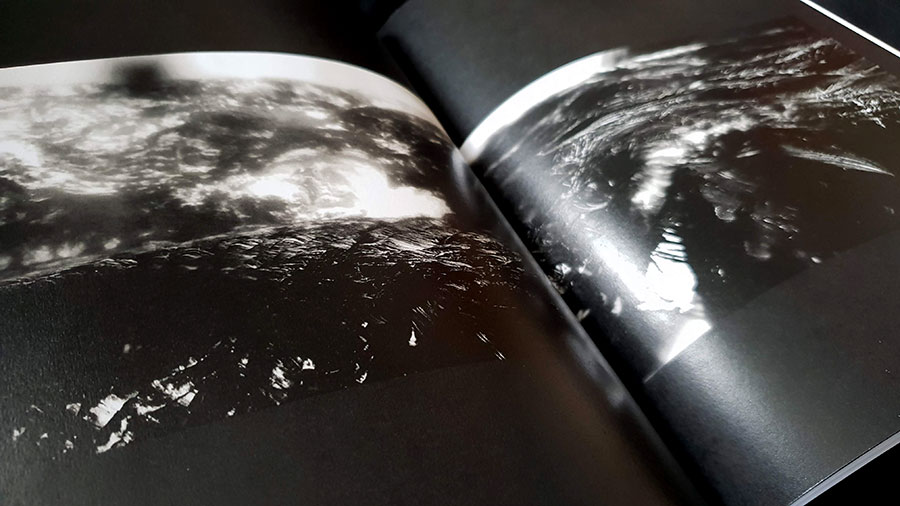

Inevitably, given the focus on things black, there’s a rather singular palette used across these works, each to varying degrees of success and not without a little fatigue and a creeping of sameness. The highlight comes, once again, from Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert, whose work has featured in previous issues of Helvete and was, by this reviewer, well received. Titled 1558 – 2016, these four pieces follow a varied approach to black with midtones and scratched texture providing interest across images that are so abstracted that little is identifiable, other than a sense of intrigue and mystery. Not quite as stunning but still well composed are parts 3-5 of Bagus Jalang’s Distraction, where his acrylic painting on paper creates negative spaces, one part topographic map, one part spectral absence. Two further entries from Max Kuiper and Faith Coloccia show that there is perhaps a successful, almost obligatory, ‘black metal theory photographic aesthetic’ at play here, with grainy abstracted textures of water, ink and decay, and with depth of field blur and saturated blacks a bonus. Other pieces are less successful, like Alessandro Keegan’s exploration of candle soot and white gouache on paper, where aimless feathered motifs floating against soot clouds are explored in five variations that seem to have had said all they had to say by the time you turn from the first example to the second.

Susanne Pratt’s Black-Noise combines the written and visual in a consideration of a similarly-named installation she created in 2013. Subtitled The Throb of the Anthropocene, her essays details how the work was created in response to Australian coal mining and its impact on both the environment and people, with the constant sound of industry creating a black noise of machinery and mining blasts. Pratt took recordings of these low frequency sounds and played them back in the gallery using speakers to influence trays of coal dust and water. Four prints are provided as photographic documentation of this work, the water and dust creating landscapes of black ripples, waves and tones. Pratt draws comparison with Carsten Nicolai’s infrasound artworks and links her considerations to black metal via just one band, Wolves in the Throne Room, whose concerns with ecology, and perhaps their more responsible image, also ensure a disproportionate presence throughout both this volume and the entire series, including an appearance in Timothy Morton’s first volume essay At the Edge of the Smoking Pool of Death: Wolves in the Throne Room; which Pratt references.

Simon Pröll’s Vocal Distortion turns to black metal’s use of the voice as a gateway into a wider discussion of how black metal obscures its delivery of information, whether it be through indecipherable vocals, unprinted or untranslated lyrics, or the obfuscation employed in some band logos. The exploration of the use of native language and topography as part of this insularity and exclusivity provides an interesting, albeit brief, diversion into black metal’s regionalism, highlighting how the genre contrasts strongly with pop culture in which English remains its lingua franca.

In Leaving the Self Behind, Nathan Snaza employs a disorientating and confounding experience of listening to Blut Aus Nord’s 2006 album MoRT as a device to explore ideas of dissolution in this volume’s longest contribution at seventeen pages. Snaza situates black metal’s idea of the annihilation of self in opposition to the Enlightenment, preferring instead a practice of Endarkenment; a term taken from a track title by another French black metal band, Obscurus Advocam. Endarkenment as described by Snaza is an inversion of Enlightenment and its goals, being an attunement to the dark which animates the world via strategies of interference. But it’s also effectively just a fancier name for the kind of fair-is-foul foul-is-fair rhetoric that can be found in any black metal album or interview.

Bert Stabler’s False Atonality, True Non-Totality mirrors his contribution to the previous volume of Helvete, being a little aimless, beginning with a several page discussion of noise theory via an interaction between Seth Kim-Cohen and Christoph Cox in the pages of Artforum, before going, well, all over the place. Stabler has a tendency to write in flowery, categorical statements that easily grate, especially when these utterances and metaphorical models seem off the mark despite their attempt at glib profundity. Black metal, for example, apparently hopes to evoke “leftover radiation from the Big Bang… or the ancient poisonous corpse-sludge of petroleum” but instead its “familiar roar is of the throng and its bloody flag flapping turgid in an icy gale, visible by the dim embers of an incinerated basilica” whatever that picturesque image is supposed to mean. Similarly, and quite categorically, black metal apparently “derives its potency from just the lack of interest in getting-anything-done,” and black metal “evokes the formlessness of physical and mental background buzz, at the same time as it attempts to be an anthem, a hymn, or a retort.” At four pages, this lack of interest in getting-anything-done it is mercifully short, huzzah.

In this volume’s final piece, Kyle McGee devotes a substantial fifteen pages to Pennsylvania’s purveyors of industrial black noise T.O.M.B. in what amounts to a paean to their sound, gushing with torrents of picturesque praise that are appropriate given how much their music conveys ideas of bludgeoning cascades and violent sanguine flows. It is because of this relation to its subject matter that there is an appropriateness to McGee’s theoretically dense yet bloody and visceral language, as typified by the glorious subtitle Grotesque Indexicality, Black Sites, and the Cryptology of the Sonorous Irreflective in T.O.M.B; unlike Stabler’s bewildering landscape of flaccid flags and dim embers. McGee views T.O.M.B.’s music with a suitably corporeal analytical model that he calls an excarnation of place, a stripping away of flesh that stands in contrast to the Church’s investment in incarnation, in which there is a profanation and deterritorialisation of spaces, objects and bodies. Of course, this doesn’t preclude one from being pragmatic and saying that this elaborate paean could equally be an exercise in hyperbole and ornamentation, reading far more than necessary into what could equally be viewed as just some hideous racket.

With its emphasis on stygian artwork and only five written contributions, this third volume of Helvete feels a little lacking. None of the written pieces really stand out in the way others have in previous volumes, and only Pröll’s Vocal Distortion and McGee’s grandiloquent consideration of T.O.M.B. manage to be both enjoyable and memorable. Otherwise, there’s an impression of diminishing returns, and given that there was never a fourth volume in this series, this murky well seems to have run dry.

Published by Punctum Books