Marking the 118th volume in De Gruyter’s Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde series, Between the Worlds: Contexts, Sources, and Analogues of Scandinavian Otherworld Journeys is a comprehensive tome running to over 700 hundred pages. As its title makes clear, this is a consideration of how otherworld journeys in the literary corpus of the Scandinavian Middle Ages are fundamentally linked to the idea of spaces between worlds. These interstitial spaces are not just found within the narratives themselves but underlie their very construction, marking points of cultural intersection between different worldviews. There’s the treatment of pre-Christian mythology in texts from the Christian period treat; the appearance of apparently Christian motifs in what is thought to be pre-Christian material; the adaption by Scandinavian texts of literature from the Europe, Ireland, and the classical Mediterranean; and the incorporation of Scandinavian narrative patterns into Finnish ones.

Marking the 118th volume in De Gruyter’s Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde series, Between the Worlds: Contexts, Sources, and Analogues of Scandinavian Otherworld Journeys is a comprehensive tome running to over 700 hundred pages. As its title makes clear, this is a consideration of how otherworld journeys in the literary corpus of the Scandinavian Middle Ages are fundamentally linked to the idea of spaces between worlds. These interstitial spaces are not just found within the narratives themselves but underlie their very construction, marking points of cultural intersection between different worldviews. There’s the treatment of pre-Christian mythology in texts from the Christian period treat; the appearance of apparently Christian motifs in what is thought to be pre-Christian material; the adaption by Scandinavian texts of literature from the Europe, Ireland, and the classical Mediterranean; and the incorporation of Scandinavian narrative patterns into Finnish ones.

Between the Worlds is comprised of seventeen contributions in all, divided into five categories of Die Altnordische und Altsächsisch-Altenglische Literarische Überlieferung, Archäologie, Mittellateinische und Keltische Überlieferungen, Die Antike Mittelmeerwelt und der Alte Orient, and Finno-Ugrische Perspektiven. The essays are written in either English or German and since this reviewer’s expertise in Deutsch is rudimentary at best, we will only be covering the English entries. For what it’s worth, the German contributions come from Matthias Teichert, Ji?í Starý, Richard North, Sigmund Oehrl, Horst Schneider, Andreas Hofeneder, Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Christian Zgoll, Annette Zgoll, and Sabine Schmalzer. Of these, the most interesting are North’s search for traces of Loki in the depiction of the Garden of Eden from the West Saxon poem Genesis B, and Starý’s exploration of interstitial worlds in two High Middle Ages Scandinavian poems, Draumkvæði and Sólarljóð. That there are only seventeen essays here spread across the supra-700 pages is indicative of the kind of considered and exhaustive content here, with nothing coming in at under ten pages and many being considerable longer.

Jens Peter Schjødt’s Journeys to Other Worlds in Pre-Christian Scandinavian Mythology is the only English entry in the first Die Altnordische und Altsächsisch-Altenglische Literarische Überlieferung grouping of essays and it provides something of a basic grounding in the themes of this entire anthology, acting as an introduction, even if it isn’t labelled as such. He argues for a certain kind of system in Scandinavian depictions of otherworld journeys, employing an axial schema in which journeys along the horizontal usually indicate a hostile encounter with the giants and are associated with Þórr, whilst travel along the vertical axis is the preserve of Óðinn and involves descent into the underworld for the acquisition of numinous power.

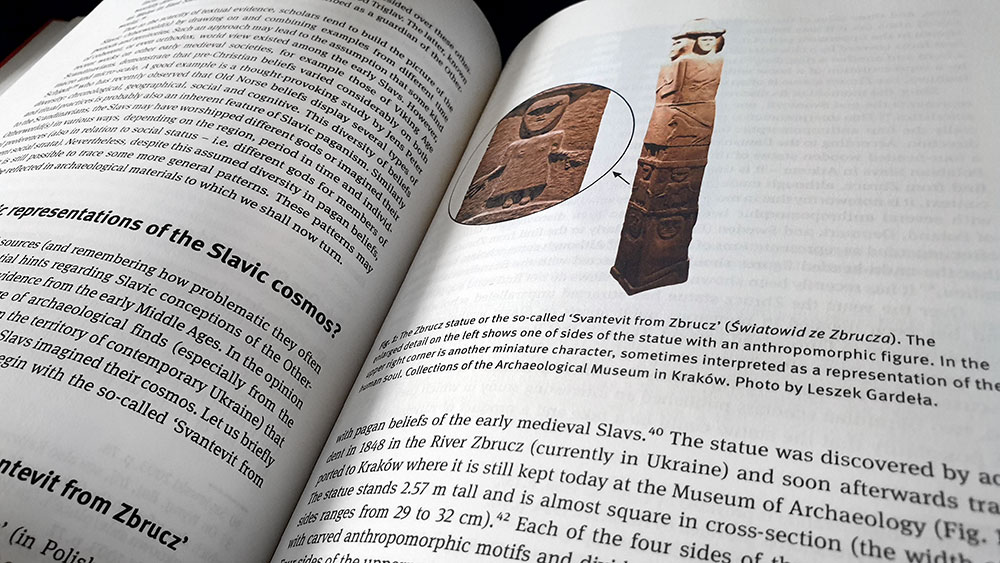

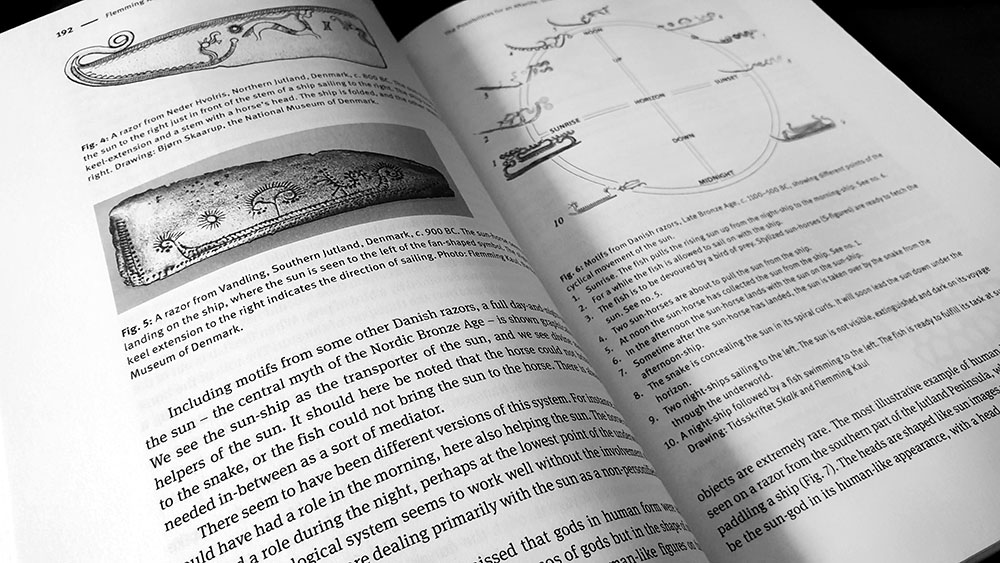

Under the heading of Archaeology, the contributions of Flemming Kaul and Leszek Garde?a both address themes found in mortuary architecture, looking within them for clues to various eschatological cosmologies. Kaul’s The Possibilities for an Afterlife. Souls and Cosmology in the Nordic Bronze Age concerns itself with ideas of conveyance to the underworld, focusing heavily on the solar symbolism of bronze objects, such as the chariot of the sun found at Trundholm in Denmark, as well as the motif of solar ships, with theoretical journey of the sun to the underworld being mirrored by the souls of the departed. With The Slavic Way of Death. Archaeological Perspectives on Otherworld Journeys in Early Medieval Poland, Garde?a provides the longest entry here, presenting a comprehensive consideration of perceptions of the afterlife in Slavic culture. Garde?a acknowledges that, given the dearth of accounts of the underworld in pre-Christian Slavic belief, this is a difficult subject to consider, with the hints that can be gleamed from folklore being collected only relatively recently (within the preceding two centuries), and representing a patchwork of information whose sources are chronologically and geographically disparate. To head off this lack of definitive sources, Garde?a goes thorough instead, exhaustively considering practically everything that could be connected with death practices, both artefactually and textually.

The only English contribution to the next section on Medieval Latin and Celtic Traditions is by Séamus Mac Mathúna who assesses various Irish analogues of motifs found in Old Norse voyage tales from both fornaldarsögur and Saxo Grammaticus’ Gesta Danorum. This is a weighty study, effortlessly introducing categories of otherworld journeys from Irish literature, in both their echtrai and later immrama genres, before considering Old Norse parallels, particularly in the reverse-euhemerised retellings of Þórr’s encounters with the giant Geirröðr, where the thunder god’s role is played by the hero Þórstein (in fornaldarsögur) or Thorkillus (in the Gesta Danorum). Mathúna writes with a healthy dose of scepticism, never stating that a link betwixt Icelandic and Irish sources is categorical, simply presenting the examples with references to previous scholars, such as Rosemary Power, who have found the idea more convincing. Mathúna reasonably concludes that while Saxo and the various authors of the fornaldarsögur may have used story patterns akin to those in Hiberno-Latin and vernacular Irish visionary literature, there’s no smoking gun, nothing that can be seen as evidence of a direct influence. Whether one finds the idea appealing or not, there is much in this piece that will be of value for anyone with a broad interest in either Celtic or Icelandic otherworld encounters.

Christopher Metcalf’s Calypso and the Underworld: The Limits of Comparison is one of two contributions here that focuses on the underworld analogues visited by Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey; with the other being Christian Zgoll’s preceding Märchenhexe oder göttliche Ritualexpertin? Kirke und Kult im Kontext der homerischen Nekyia, in which Circe and her island are discussed. Metcalf’s approach, as its circumspect title suggests, is the less fun of the two, being cautious about the comparison between the underworld and the island of the enchantress Calypso. Despite his scepticism, this is an idea that has been extant in scholarship for well over a hundred years, drawing on commonalities betwixt the island and depictions of the underworld in Greek myth, as well as employing comparative approaches from broader Indo-European mythology. Metcalf finds both those methods and the entire idea of Calypso as a veiled death goddess less convincing, and as a result, comes across as a bit of spoilsport and no fun.

Two of the longest contributions here come from Clive Tolley and Frog in the final section on Finno-Ugric perspectives, although Tolley’s “Hard it is to stir my tongue”: Raiding the Otherworld for Poetic Inspiration is not as focussed on matters Finno-Ugric as its placement within this grouping might suggest. Instead, Tolley presents an utterly thorough 94 page exploration of encounters with the underworld as part of the acquisition of the gift of poetry, spreading his net wide to consider the motif from sources Norse, Finnish, Siberian, Greek, Anglo-Saxon, and Celtic in strains Irish, Scottish and Welsh. This makes for a vital contribution, one that, by its very nature, embraces a variety of themes beyond just those of poetic inspiration and otherworld journeys. The 124 pages of Frog’s Practice-Bound Variation in Cosmology? A Case Study of Movement between Worlds in Finno-Karelian Traditions feels more at home in this final section with its evident focus on Finno-Karelian myth and practices. This is another piece that justifies the entry price, with Frog exploring not just otherworldly travel in the Kalevala, but also so much more. He extends the investigation into matters experiential, considering similarly motifs in the work of traditional tietäjä (magic workers) and Karelian lamenters.

Even if only half the contributions are accessible for us monoglots, Between the Worlds is a valuable addition to the library of anyone with an interest in Scandinavian eschatology and otherworld journeys in general. There’s little here that feels well-trodden or overly familiar, with the authors each providing interesting avenues to explore. It is present to the usual high quality of De Gruyer, with the mass of pages bound in a sturdy red cloth hardback.

Published by De Gruyter