Subtitled The Afterlife of the Eddas and Sagas, Jon Karl Helgason’s Echoes of Valhalla has the dubious distinction of being the first book to be reviewed at Scriptus Recensera in which the opening paragraph references the dire and perpetually unfunny 1990s sitcom Friends. Helgason uses the show’s passing reference to a peripheral character who is nicknamed Gandalf as an example of how something with roots 1000 years ago could so suffuse popular culture that it now exists independently of its origins. In this instance, the name Gandalf can be traced back to the list of dwarf names found in the Old Norse poem Völuspá, where it sits alongside the names of twelve of the thirteen dwarves that join Gandalf and Bilbo Baggins on their adventure in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Whether it is from reading Tolkien’s works, seeing the film adaptions of Ralph Bakshi or Peter Jackson, or even encountering the characters in the Lego video game versions of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, most people, even those versed in skaldic poetry and the Eddas, will inevitably think of some incarnation of Gandalf the wizard when encountering that name, rather than one of several primordial dwarves. This is exemplary of what Helgason finds fascinating, that texts written centuries ago in the isolated rural areas of his native Iceland have become part of “our (almost) universal cultural memory” and have seen reproduction in comics, plays, travelogues, music and film.

Subtitled The Afterlife of the Eddas and Sagas, Jon Karl Helgason’s Echoes of Valhalla has the dubious distinction of being the first book to be reviewed at Scriptus Recensera in which the opening paragraph references the dire and perpetually unfunny 1990s sitcom Friends. Helgason uses the show’s passing reference to a peripheral character who is nicknamed Gandalf as an example of how something with roots 1000 years ago could so suffuse popular culture that it now exists independently of its origins. In this instance, the name Gandalf can be traced back to the list of dwarf names found in the Old Norse poem Völuspá, where it sits alongside the names of twelve of the thirteen dwarves that join Gandalf and Bilbo Baggins on their adventure in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Whether it is from reading Tolkien’s works, seeing the film adaptions of Ralph Bakshi or Peter Jackson, or even encountering the characters in the Lego video game versions of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, most people, even those versed in skaldic poetry and the Eddas, will inevitably think of some incarnation of Gandalf the wizard when encountering that name, rather than one of several primordial dwarves. This is exemplary of what Helgason finds fascinating, that texts written centuries ago in the isolated rural areas of his native Iceland have become part of “our (almost) universal cultural memory” and have seen reproduction in comics, plays, travelogues, music and film.

Given this evident fascination, what is presented here is not a pedantic discussion of how pop culture interpretations of Norse mythology differ from the source material. Instead, Helgason views these modern retellings as a continuation of a metafictional tendency in the treatment of Norse myth that dates back to at least Snorra Edda in which Snorri Sturluson’s retelling of the story of Óðinn’s theft of the mead of poetry allows us to read fiction about the origin of fiction, and its constant ingestion. Just as Óðinn ingests the mead of poetry, so, Helgason argues, Snorri and other post-conversion poets used an inventive ‘digestion’ of earlier texts to create mnemonic devices to better understand both the past and the art of poetry itself.

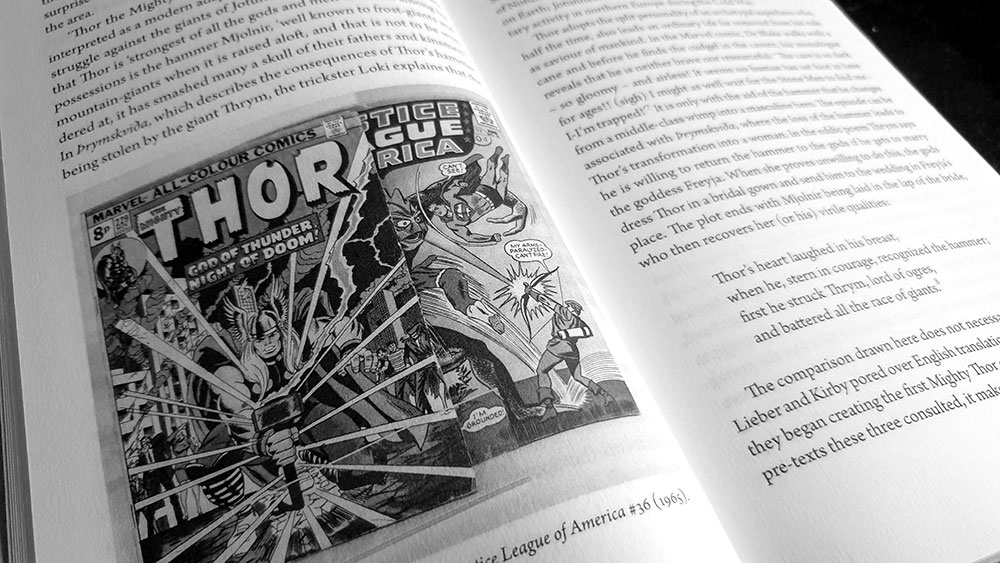

The first focus of this digestion is Þórr who finds his most obvious, though by no means only, comic representation in Marvel’s Mighty Thor, “the most exciting superhero of all time” as the cover of his debut in Journey into Mystery #83 injudiciously proclaims with two exclamation marks. Helgason shows how from the outset, this Thor had little reliance on his mythic predecessor, with a far great influence being found in similar figures in previous comics, all of which follow a familiar pattern. Indeed, the ur-text for Stan Lee, Larry Lieber and Jack Kirby were not the Eddas or skaldic poetry, but rather the very comics in which they were immersed, with a number of precedents for the idea of the Norse thunder god transplanted into the modern world, including some in which a human awakens, or becomes the embodiment of Þórr. Kirby had a hand in several of these, including a story in #75 of DC’s Adventure Comics (in which the villain Fairy Tales Fenton masquerades as a magical hammer-wielding Þórr to rob banks), and an issue of Tales of the Unexpected from 1957 in which a gold-digger discovers Þórr’s hammer and considers robbing banks with it, before its owner turns up and claims it back.

In the second chapter, Helgason takes a significant chronological leap backwards and returns to Snorri’s own treatment of this topos, considering in-depth the ambiguity surrounding his role as author. Helgason mentions how Snorri is rarely physically credited as the author on many of the works he came to be associated with, and highlights his role as a compiler, and therefore as someone who is but one link, albeit a significant one, in a chain that extends from the uncredited skalds to modern comic book writers (a class also historically subjected to working anonymous and receiving insufficient credit).

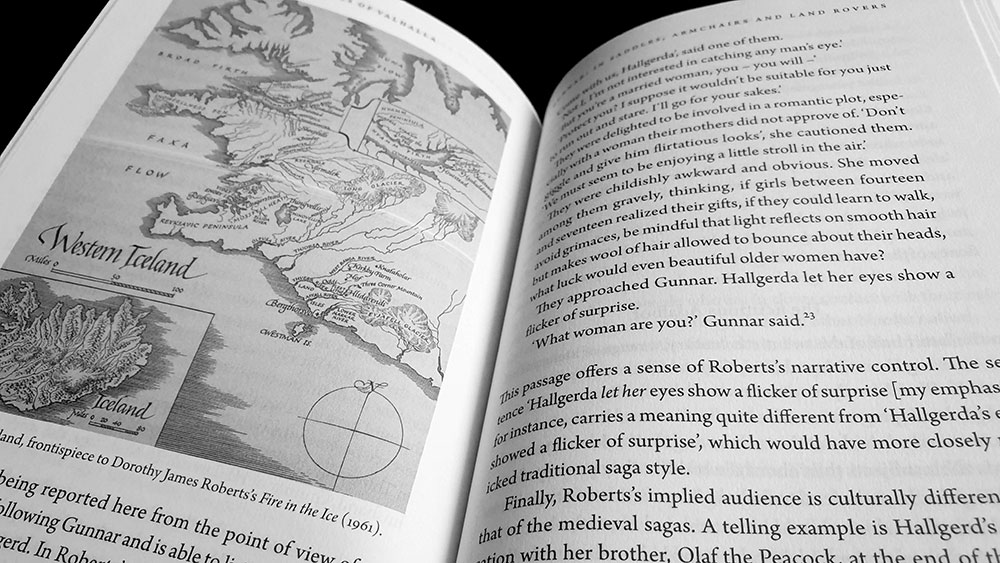

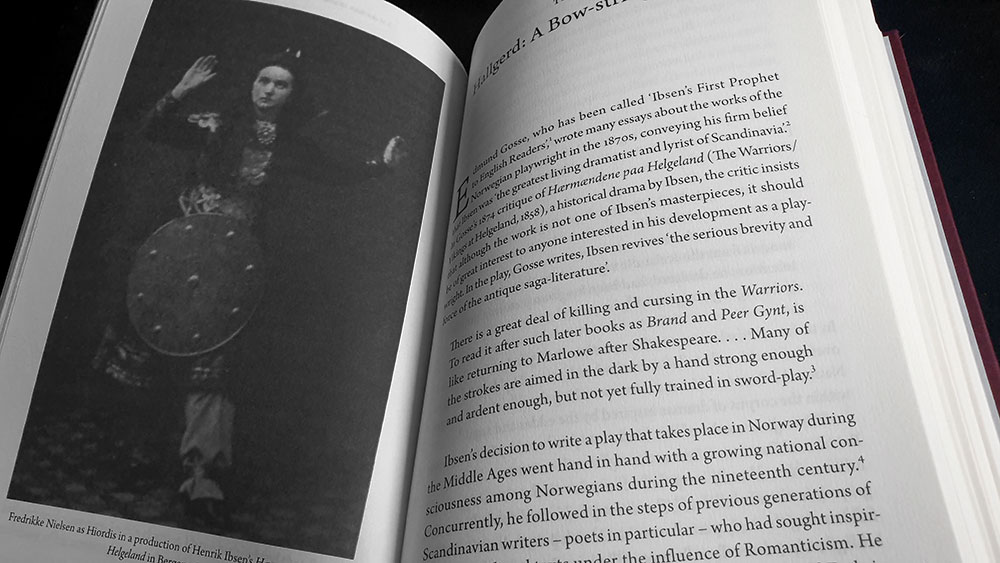

Focus then turns to the stage, beginning with a consideration of Henrik Ibsen’s 1857 play Hærmændene paa Helgeland, set during the post-conversion time of Erik Blood-axe, with Helgason noting the through-line between its heroine Hjørdis and another of Ibsen’s characters, the titular Hedda Gabler, whom he would immortalise decades later in 1890. In slightly less detail, Helgason also looks at the relevant works of Gordon Bottomley (The Riding to Lithend) and Thit Jensen (Nial den Vise), before moving on to the fourth chapter with its discussion of travel writers, in which their explorations of Iceland more often than not went hand in hand with a fascination with the sagas, their characters and locations.

With the fifth chapter and its consideration of music, Helgason begins with references to Led Zeppelin, attempting to position them as a link between two diverse musical examples of the afterlife of the eddas: Norse-inspired classical music as typified by Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and contemporary Viking metal. Helgason centres this discussion on the motif of Valhalla, showing how the perhaps overstated idea of a glorious death and equally glorious afterlife has held a particular and enduring attraction for musicians, often becoming shorthand for conceptions of Norse mythology in its entirety. Unfortunately, just as such an idea limits the complexity of myth, so applying that model to analysing an art form simplifies its assessment and as a result, this is a relatively brief survey of Viking metal. There’s no real noting of the history, no mention of offshoots like the Norse ritual music of Wardruna and their imitators, and only a few bands are mentioned by name, with one of these being a little known power metal band from Mexico, Mighty Thor, whose outsize presence is cemented by them being the only band represented here in photos, twice (one a frankly ridiculous promo photo and the other a tiny, practically pointless album sleeve). While a comprehensive history of the genre isn’t to be expected, the level of detail seems slight when compared to how the previous chapters have addressed their respective subject matter, and there is much more than could have been worth discussing in a deeper dive.

Finally, Helgason turns to cinema, once again beginning with a quirky reference, in this instance to the Monty Python-aligned film Erik the Viking, before taking a deep dive into Viking-themed films, the most notable of which went with the stunningly imaginative title The Vikings. There’s Roy William Neill’s so-named silent film from 1928, and Richard Fleischer’s sword-n-sandals-era The Vikings from 1958. Although the latter could be said to paint an implausible image of Norse Vikings, Helgason returns to his central premise, wryly noting that the same could be equally true of the sagas and eddas themselves.

In all, this is an enjoyable read, with Helgason having an amiable style and clear narrative voice. Not all sections will necessarily appeal to everyone, with, for exampl, drama and travelogues being somewhat obviously of little interest to this reviewer with her scant summary thereof. Echoes of Valhalla runs to 240 pages and is bound in red with grey endpapers, all wrapped in a nice glossy dust jacket.

Published by Reaktion Books