In my mind, I always find this book from Three Hands Press occupying the same mental space as Serpent Songs from Scarlet Imprint. Both are compendiums of essays on various witchcraft topics, with a focus on what is referred to as traditional witchcraft. And both take themselves pretty seriously.

In my mind, I always find this book from Three Hands Press occupying the same mental space as Serpent Songs from Scarlet Imprint. Both are compendiums of essays on various witchcraft topics, with a focus on what is referred to as traditional witchcraft. And both take themselves pretty seriously.

With eighteen authors contributing to this collection, there’s a wealth of viewpoints and writing styles, with both sides of the Atlantic getting some coverage, and styles both academic and anecdotal being featured. By accident or design, North America gets the early focus with Douglas McIlwain talking briefly about his stateside family tradition, while Cory Thomas Hutcheson’s Killing the Moon is a thorough investigation of witchcraft lore from the mid-to-southern Appalachians. The lunacide of the title (and its solar analogue) is an initiatory ritual element found throughout the south, ranging from the Appalachians to the Ozarks. A focus on folk practices is found elsewhere in this volume, with David Rankine considering the influence of witchcraft and natural magic on the grimoire tradition (a reversal of the common narrative of low witchcraft borrowing from high magic), while Gary St. Michael Nottingham covers similar territory with a survey of conjure-charms from the Welsh Marches. As with Rankine’s essay, Nottingham shows an interaction between the grimoire tradition and folk magic, documenting the source texts from which various charms would have been sourced.

There are several essays that take a more conceptual, rather than practical or documentary, approach, using themes from traditional witchcraft as lenses through which a greater philosophical picture can be explored. Most notable of these is the longest essay here at 45 pages, Martin Duffy’s The Cauldron of Pure Descent, which considers that magical accoutrement most firmly associated with witches, the cauldron. Given the length of his essay, Duffy is able to, if you’ll pardon the obvious, throw many things into the pot, creating a thorough exploration that embraces not just witchcraft but Palo Mayombe, alchemy, and various strands of mythology. In The Man in Black, Gemma Gary considers the devil in witchcraft, although less as the horned master of Sabbaths and more as the enigmatic stranger encountered by witches in times of need and moments of isolation and reflection. Michael Howard’s Waking the Dead almost rivals Duffy’s length with its investigation of necromancy which begins somewhat encyclopaedically, rather than discursively, before finding its feet towards the end when Howard assimilates the assiduously assembled information into a sabbatic craft context.

Andrew Chumbley does rather well contribution-wise for someone who passed on in 2004, providing two pieces, The Magic of History: Some Considerations and Origins and Rationales of Modern Witch Cults. As their titles suggest, both are broad in their concerns, rather than specific, briefly surveying the history of modern witchcraft and the intersection with Chumbley’s own sabbatic craft brand of traditional witchcraft. Also participating from beyond this mortal veil is Cecil Williamson, founder of the Museum of Witchcraft, whose rather short article looks at two little known magical techniques, moon-raking and the ritual of the shroud. This slight essay previously appeared in The Cauldron, and is prefaced with a preamble by that magazine’s editor, Michael Howard, which is only one page shorter than Williamson’s actual words.

As one would expect, the sabbatic craft makes a significant contribution to this volume, with Chumbley’s two pieces being joined by The Blasphemy of Things Unseen by Daniel Schulke. Schulke writes in his usual florid style, embellishing his words with archaic flourishes in a meditation on the role of night, darkness, secrecy and the void in witchcraft and specifically the sabbatic cultus. But the most interesting exploration of Chumbley’s oeuvre comes from Jimmy Elwing with Where the Three Roads Meet. Subtitled Sabbatic Witchcraft and Oneiric Praxis in the Writings of Andrew Chumbley, this is an admirably sanguine and removed biography of Chumbley, providing a meticulous analysis of the themes in his writing; and one of the highlights of this compendium.

Elsewhere, Radomir Ristic’s Unchain the Devil considers Serbian witchcraft and seems to act as a teaser for their full book Witchcraft and Sorcery of the Balkans now available from Three Hands Press. Levannah Morgan’s Mirror, Moon and Tides is the only purely experiential piece here, clearly and authoritatively explaining their personally grounded techniques of mirror magic with little need to recourse to the authority of either tradition or the academy.

There is a certain rigour to most of the material here, whether it’s deference to academia with a thorough embracing of citing and referencing, or less thoroughly, an explicit identification of experiential knowledge or tradition. The same cannot be said for the rather anomalous contribution from Raven Grimassi, who plays to type and writes with the broad and speculative strokes one would expect of a Llewellyn author. His piece, Pharmakeute, is typical of Llewellyn woolly thinking, full of unreferenced references to unspecified ancient times and unspecified ancient ancestors; a precedent set in the first sentence which boldly and broadly states “ancient writings depict the witch as living among the herb-clad hills” – which writings, which witch, which herb-clad hills? In an amateur attempt at anthropological psychology, Grimassi speculates that a magical worldview may have been influenced by the ancestral experiences of living in forests – these ancestors and their wooded location remain unidentified, adrift in some imagined olden days, distant from all the other unspecified ancients who can’t have had a magical worldview because they lived on hills, plains, mountains, in caves, by river and lakeside and, I don’t know, maybe anywhere that wasn’t a potentially lethal forest. While discussing mandrakes, Grimassi wonders if the idea that mandrake had to be harvested using a dog pulling on the plant (lest the harvester be killed in the process) was created by witches in order to discourage laypeople from effectively raiding their stash. Yeah, cool story bro, except that the technique has a significant pedigree dating back to at least the first century CE where the Romano-Jewish historian Josephus made the first written mention of a presumably well extant belief. I guess some ancient witch from the olden days must have been playing a long game and dropped the skinny to Titus Flavius so he could spread the word on their behalf.

With its diverse collection of writers and subject matter, there’s something in Hands of Apostasy for everyone; well, everyone interested in traditional witchcraft that is – if you’re after something on fly fishing this may be less useful. The highlights are definitely Martin Duffy’s exhaustive consideration of the cauldron and Jimmy Elwing’s analysis of Andrew Chumbley. The low lights go without saying.

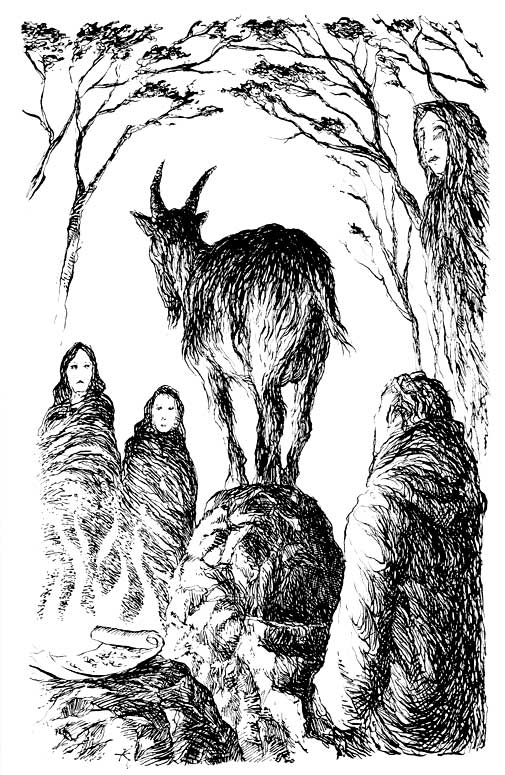

Hands of Apostasy comes in standard hardcover edition of 1000 copies, in full pewter book cloth, with a glossy fully colour dust jacket. The internal pages are made of a stark, not entirely attractive white stock and the text is formatted in a capable, functional style. Almost all of the nineteen articles are prefaced with illustrations by Finnish engraver Timo Ketola, whose finely rendered volumetric style provides the book with a cohesive, slightly timeless style that is, given his background, just a tiny bit evocative of metal aesthetics. A limited special edition of 63 copies in quarter goat with corners, hand marbled endpaper, and slipcase, is now, of course, sold out.

Published by Three Hands Press.

Thank you for your comments regarding my text on Chumbley. I hope to publish more articles in the future, which will provide a deeper analysis than the one provided in the “Where the Three Roads Meet”. Also glad to have found your blog — keep up the good work!

Looking forward to reading such articles, Jimmy. Really did enjoy the one in this volume.

Glad that you enjoyed my contribution to Hands of Apostasy – its always heartening to see that one’s efforts have been well received! Cheers!

You’re welcome, Martin. A mark of a good piece is that it makes you see connections hitherto unseen. This piece did that, as did your contribution to the first issue of Clavis.