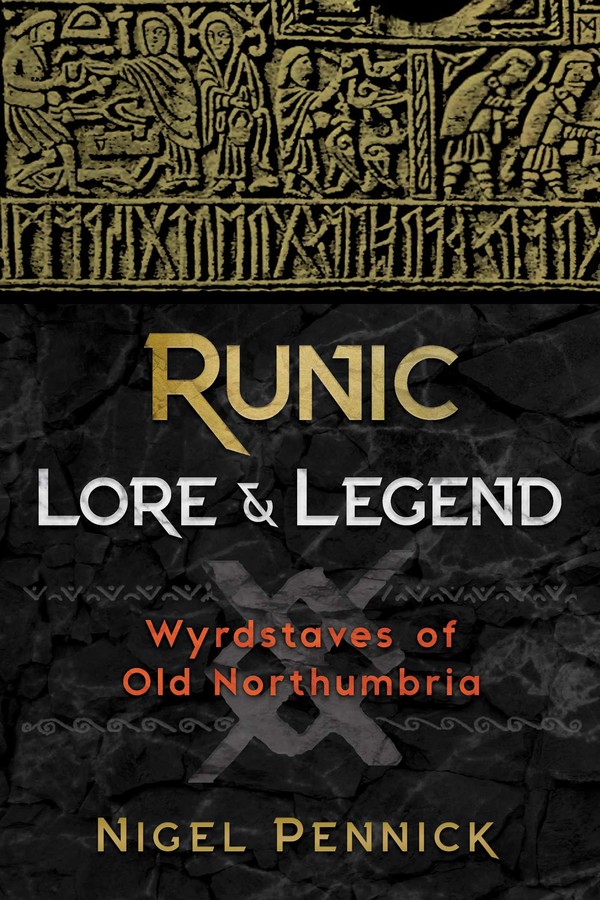

Originally released in 2010 as the broadly titled Wyrdstaves of the North, this book from Nigel Pennick has now been rereleased in 2019 by the Inner Traditions imprint Destiny Books, with a new title that is even broader, but with a subtitle that is more specific. As this subtitle indicates, the focus here is on a version of the 29 runes Anglo-Saxon Futhark (itself an expansion of the 24 runes of the Elder Futhark) that around 800CE had four more runes added to it, thereby completing a fourth aett/airt with Calc, Cweorth and Stan, and one standalone final rune, Gar.

Originally released in 2010 as the broadly titled Wyrdstaves of the North, this book from Nigel Pennick has now been rereleased in 2019 by the Inner Traditions imprint Destiny Books, with a new title that is even broader, but with a subtitle that is more specific. As this subtitle indicates, the focus here is on a version of the 29 runes Anglo-Saxon Futhark (itself an expansion of the 24 runes of the Elder Futhark) that around 800CE had four more runes added to it, thereby completing a fourth aett/airt with Calc, Cweorth and Stan, and one standalone final rune, Gar.

It’s impossible to overstate Pennick’s role and influence in contemporary runic magic, being something of the English counterpart to the American Stephen Flowers, with books by both authors sitting alongside each other in the shelves of Scriptus Recensera and surely many other occult libraries. While Pennick has dealt broadly with all manner of runes and other elements of paganism and folk traditions over the last forty years, the Anglo-Saxon Futhark and its Northumbrian variant is not something he has shied away from, and many of his books include its additional runes as a matter of course. With Runic Lore & Legend, this inclusion becomes a focus and Pennick contextualises the futhark within its Northumbrian locus, a site where various cultures and traditions intermingled.

This context is substantial and consists of several preparatory chapters, rather than diving headfirst into the runes themselves. After a brief but comprehensive survey of Northumbria’s history of invasions and colonisations, Pennick turns to a considerable meditation on the place and space, discussing what he titles the spirit landscape of Northumbria. Here, he discusses various features of the land and how they would have been perceived and used as part of a metaphysical framework, and how this use evolved over time with the successive waves of colonisers. It’s an effective way to preface what follows, building a solid and palpable sense of place. This purlieu is contextualised still further in a spatial and horological sense with a chapter on Northumbrian geomancy, in which Pennick talks of the division of the landscape and the year into quarters and then eights. This isn’t something necessarily unique to Northumbria, or to Pennick’s writing for that matter, and reflects practices found throughout Germanic Europe, from which he draws examples by way of comparison.

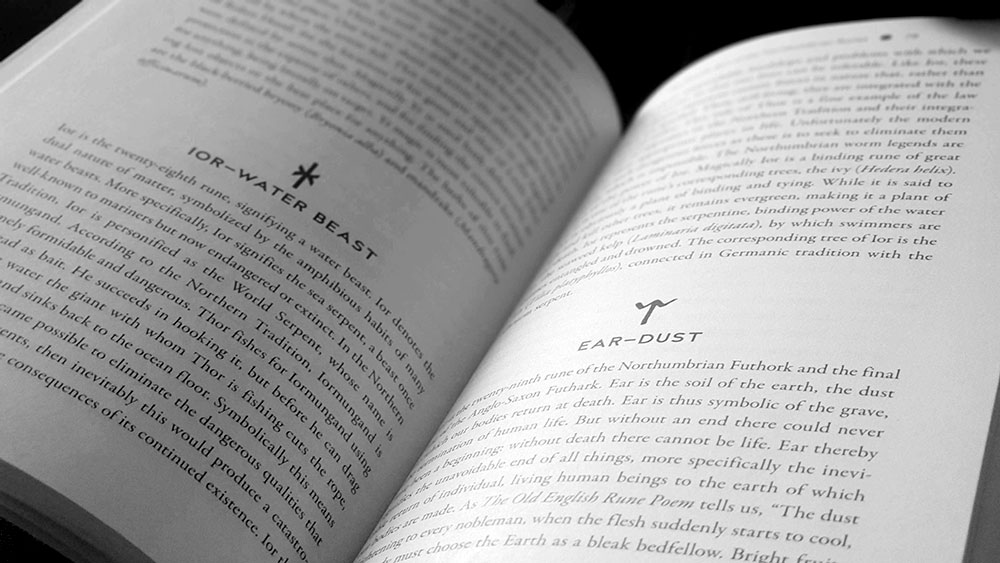

The sections on the runes themselves, divided into chapters for each airt, uses a familiar pattern, with each rune (along with its name and core meaning) acting as a heading, followed by usually up to a page of explanation. These explanations give a synopsis drawing from rune poems, usually The Old English Rune Poem, naturally, along with examples from a concept’s mundane equivalent, suggestions of magical usage, and closing with tree and herb correspondents.

Pennick concludes Runic Lore & Legend with several chapters investigating examples of the runes and their import in Northumbria and its legends. This effectively allows for a greater exploration of themes associated with a select few runes, as not all are covered. Up for a greater focus are Haegl and the symbolism of the number nine, along with the magical use of knots and knotwork patterns; Ing and various ideas associated with kingship, including divine kings and the Christian perpetuation of this concept of apotheosis with canonisation of saints; and Yr and a raft of associations with archery. The most significant one, in size as well as relevance to this reviewer, is a deep dive into serpent legends as a manifestation of the Ior rune and Iormungand.

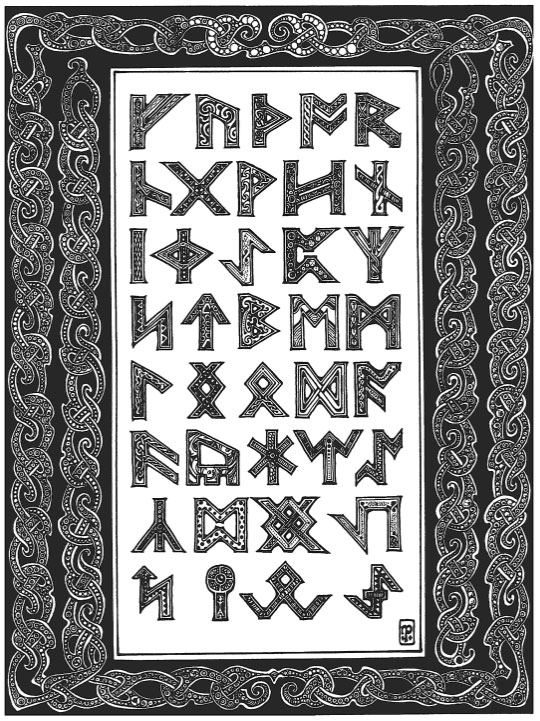

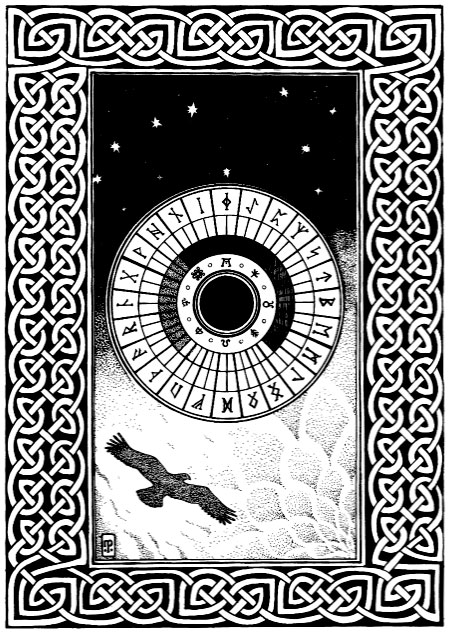

Given the amount that Pennick has written on these subjects over the years, anyone familiar with his work will find certain areas that are, well, familiar. The explanation of each rune is particularly notable for this, with the symbolism consistent, as one would expect, and while the entries are not simply cut and pasted from Pennick’s previous publications, it’s clear that they provided the template for what is here, albeit with significant editing and rewriting that moves it beyond lazy regurgitation. The same is true with images, where there’s a return of some illustrations used in other Pennick books, such as his illuminated runes (which someone needs to digitise and turn into a font) and a rune circle with bird in flight, as seen on the cover of the classic Runic Astrology from 1990.

Runic Lore & Legend is laid out to the usual high standard of Inner Traditions/Destiny Books, with text design by Virginia Scott Bowman and layout by Debbie Glogover. The body is set in Garamond, all classic and eminently readable, contrasting nicely with the sans serif Avenir used for subheadings. Chapter headings use Mehmet Reha Tugcu’s dynamic Njord face, which also features prominently on the cover, providing a perfect modern type choice that suggests the angular nature of the runes without in any way feeling obvious. The chapter headings sit atop a gradient-feathered photograph of a contemporary runic bracteate, which if we were to be picky (what, moi?), features the 24 runes of the Elder Futhark and not the full and more appropriate Northumbrian compliment of 33. It should also be meanly mentioned that the designers don’t seem to have had access to a runic typeface with all of these 33 characters, as the rune faces used to head up each rune’s section are inconsistent, some crisp and angular, some distressed and some looking bespoke and hand drawn, all with a distractingly obvious variety of weights.

Photographs feature throughout as illustrations, often acting to document Northumbrian features of notes, such as runes in situ, and in one intriguing instance, a lupine doorknocker at a church in York, which Pennick suggests is a representation of Fenrir swallowing Odin. Twinned with these photographs are a selection of reproduced drawings and etching, drawn from a variety of sources and predominantly used to illustrate apropos scenes from folklore and legend.

Published by Destiny Books.