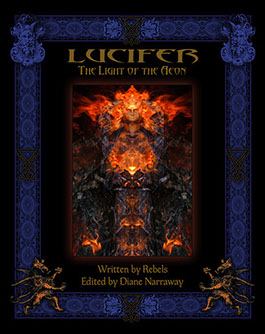

The popularity of Lucifer seems to be surging of late with the recent compendium The Luminous Stone: Lucifer in Western Esotericism from Three Hand Press, a similar anthological work on its way from Anathema Publishing, and, of course, Peter Grey’s significant 2015 opus Lucifer: Princeps; not to mention the surfeit of Lulu and Createspace generated tomes that fill your Amazon recommendations with their appalling cover art, clunky sigils and poor typeface choices. Black Moon Publishing’s foray into this tumescent Luciferian field brings together a vast array of contributors, sixteen in all, variously presenting essays, poems and a smattering of images.

The popularity of Lucifer seems to be surging of late with the recent compendium The Luminous Stone: Lucifer in Western Esotericism from Three Hand Press, a similar anthological work on its way from Anathema Publishing, and, of course, Peter Grey’s significant 2015 opus Lucifer: Princeps; not to mention the surfeit of Lulu and Createspace generated tomes that fill your Amazon recommendations with their appalling cover art, clunky sigils and poor typeface choices. Black Moon Publishing’s foray into this tumescent Luciferian field brings together a vast array of contributors, sixteen in all, variously presenting essays, poems and a smattering of images.

The first section, Awakenings, compiles a multitude of contributions within a relatively slight space, mostly short, personal anecdotes outlining people’s occult journey’s within which Lucifer, in some form, has played a role. There are nine of these in all, and at the beginning they are largely interchangeable, with similar writing styles depicting similar journeys. There’s often an estrangement from organised religion, which is followed by an encounter with an, at first, ambiguous supernatural figure whose identity is later confirmed to be Lucifer.

Speaking, erm, personally, the personal anecdote has never done much for me as a contribution to devotionals like this. While I realise that this approach is, in some ways, the very definition of a devotional, it seems to lack something when that experience isn’t expanded upon, and given context within a greater anthropological or mythological framework. Otherwise, it remains just a personal testimony, the equivalent of a fireside ghost story, which the reader has to either accept or dismiss; and as a somewhat pragmatic reviewer of books about magickal shenanigans, my default setting is the latter.

The contributions in Awakenings are often short and it isn’t until the second section, Love, Light and Laughter, that one realises why this is, with many of the stories now picking up from where they left off. Proof, mayhaps, that I didn’t read the introduction too carefully. This is not an entirely satisfactory device, given that the somewhat interchangeable nature of the contributions makes it hard to keep track of where the narrative is up to. And then there’s the additional wrinkle of perhaps not really wanting to hear anything further from a particular contributor after the introduction they’ve made in Awakenings. Because of how integral this multiple section structure is, it is worth mentioning the names of the nine contributors who reappear in this capacity: Dianne Narraway, Geraldine Lambert, Laurie Pneumatikos, Sean Witt, Eirwen Morgan, Richard K. Page, Jaclyn Cherie, Rachel Summers and Teach Carter.

This format ultimately makes Lucifer: The Light of the Aeon something of a struggle to get through. Personal reflections of people’s experience with organised religion, and their all too similar awakening to their inner rebel, are just not engaging. On top of that, the rebellion feels rather entry level and earnest, with nothing truly transgressive or adversarial, and just an all too obvious kicking against the pricks of an equally dull brand of Christianity.

It is only when this personal formula is abandoned that things begin to pick up and there’s more of a sense of focus. In Angels and Daemons, the cast of authors take a more exegetical approach with various, less-anecdotal explanations of Lucifer. These do largely cover the same ground because there’s only so much ground to cover when it comes to exploring Lucifer’s source material. These contributions still suffer, though, from the book’s structural device, feeling piecemeal in some instances, while in others they’re cast adrift from the anecdotal context of the previous two sections.

The other issue that arises here is that the less than stellar quality of some of the writing, which may have been protected by the personal nature of the previous entries, is laid bare when broader ideas have to be presented. In one piece, non sequiturs abound, conclusions are questionable, and facts are fuzzy: there’s a nonsensical reference to “biblical gnostics,” whoever they’re supposed to be, and a lazy, or at least poorly articulated, claim that ‘gnostic’ means ‘knowledge,’ when obviously it’s ‘gnosis’ that means ‘knowledge,’ not the adjective form.

The remaining four sections continue this same formula of slices from various contributors, focusing successively on blood and fire (identified as two of Lucifer’s more famous associations), magick (with a variety of broad accounts of people’s personal approach to ritual praxis, followed in some instances with specific exercises), questions concerning Lucifer’s consort (straw poll suggesting most contributors don’t see him as having one), and what could be described as concluding thoughts and miscellany. Naturally, these various shards range in quality, with some of the writing coming across as if they were written as an obligatory assignment simply predicated by the theme of that section. This is particularly noticeable in the discussion over whether Lucifer has a consort, with many of the authors writing as if it’s the first time they’ve pondered the question, and therefore spending the length of their contribution thinking out loud in print, as they try to work it out.

In all, the writing in Lucifer: The Light of the Aeon appears to come from a very personal place. There are no half-hearted adherents here, with a sense of a great deal of affection and devotion being paid to Lucifer. Your mileage may vary as to what weight such sincerity carries for you, but based on the effusive reviews on Amazon, it certainly works for some people.

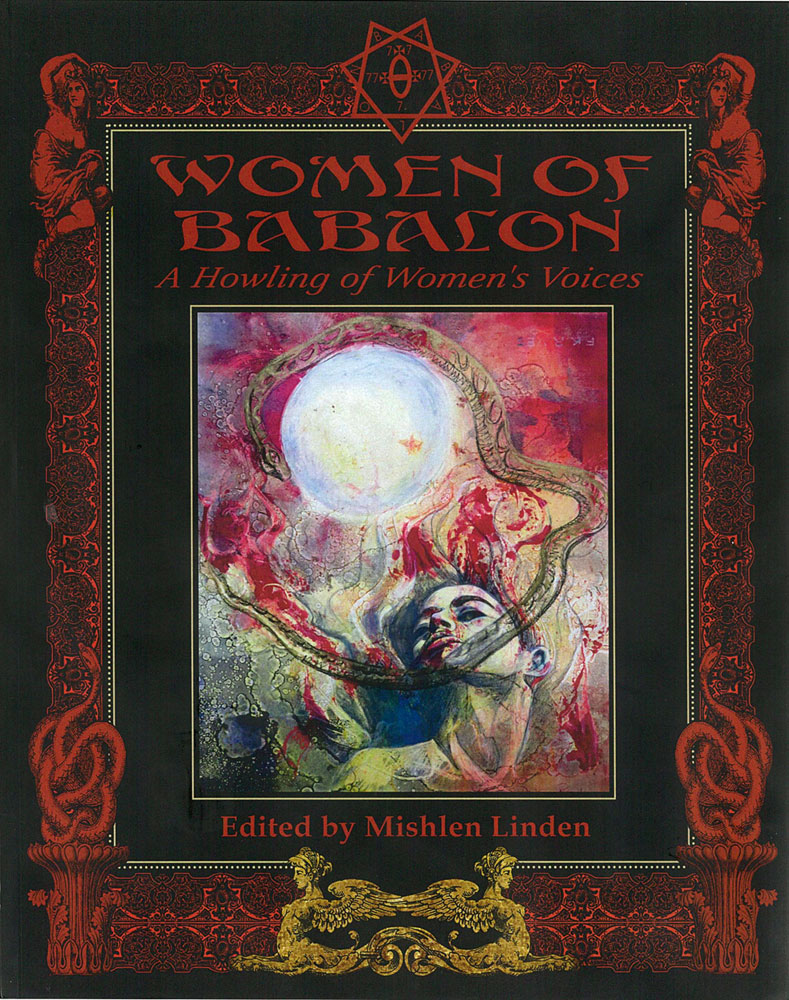

As with the previously reviewed Women of Babalon: A Howling of Women’s Voices, I have reservations about the trademark Black Moon Publishing style with its 8×10 dimensions and use of wide decorative borders on every page. The dimensions make the book unwieldy, cumbersome to hold, and not conducive to being read, especially with the additional weight that comes from being over 300 pages long. This length is, no doubt, exacerbated by said border, which, whilst appealing in an over-the-top gothic aesthetic sense, does limit the amount of words that can appear on the page. It also overwhelms the occasional graphic contributions, which could all benefit from being reproduced larger and free of the competing rococo.

Lucifer: The Light of the Aeon has a companion volume, Songs of the Black Flame, also published by Black Moon Publishing, with many of the authors featured here returning for what is largely a compilation of Lucifer-themed poetry and artwork.

Published by Black Moon Publishing