Part of Cornell’s Myth and Poetics II series, in which literary criticism is integrated with anthropological approaches to mythology, Old Norse Folklore is a collection of essays by Stephen A. Mitchell, the Robert S. and Ilse Friend Professor of Scandinavian and Folklore at Harvard University. Almost all of the essays have been previously published across a variety of books and journals, so anyone familiar with Mitchell’s output, and Norse academia in general, will probably have come across at least one of them before. It’s a joy to have all of them in one place, and this feeling is aided by the inclusion of some of the essays being made available in English for the first time.

Part of Cornell’s Myth and Poetics II series, in which literary criticism is integrated with anthropological approaches to mythology, Old Norse Folklore is a collection of essays by Stephen A. Mitchell, the Robert S. and Ilse Friend Professor of Scandinavian and Folklore at Harvard University. Almost all of the essays have been previously published across a variety of books and journals, so anyone familiar with Mitchell’s output, and Norse academia in general, will probably have come across at least one of them before. It’s a joy to have all of them in one place, and this feeling is aided by the inclusion of some of the essays being made available in English for the first time.

Joy may seem a strange emotion to attach to academia but it is palpable here, with Mitchell celebrating his tenure at Harvard through this collection of work, noting that the selection process was a joyous albeit daunting one. He details how it involved casting the net wide not just in terms of topics but theories and approaches, testifying to experimenting with a variety of theoretical pathways over the years, unwilling to dismiss any method out of hand. This positivity is echoed in the wonderful sense of blithesome collegiality to be found in Mitchell’s introductory acknowledgements, taking the opportunity afforded by a collection such as this to reflect on the many people he has met along the academic way. There’s gratitude for the inspiring (and “occasionally unintentionally terrifying”) teachers, for academic organisations and libraries, for the faculty at Harvard (with Mitchell in his fifth decade as a member), and for all the remaining but otherwise previously unmentioned Nordicists from across the field, listed alphabetically for completeness across half a page from Adalheidur to Zachrisson.

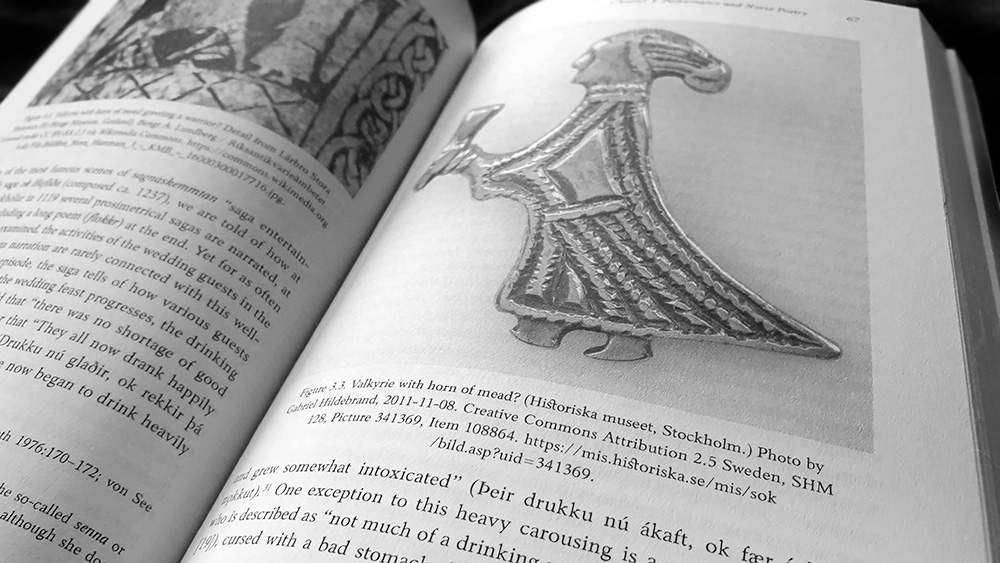

Old Norse Folklore is divided into three sections, Orality and Performance, Myths and Memory, and Traditions and Innovations. The first of these groupings is something of a technical grounding, with four essays previously published in the books Folklore in Old Norse – Old Norse in Folklore (University of Tartu Press), John Miles Foley’s World of Oralities (Arc Humanities Press) and the heretofore-reviewed Handbook of Pre-Modern Nordic Memory Studies (de Gruyter), as well as Harvard’s Oral Tradition journal. There are no in-depth considerations of mythic elements here, and instead the focus is on the mechanics of folklore, poetry and its performance. It is this intersection betwixt myth/folklore and performed poetry that looms large within the pieces collected her, with these themes consistently arising across the pages. Equally prominent is Sturla Þórðarson’s Sturlu þáttr, which is used as a significant source text in Mitchell’s Performance and Norse Poetry, as it depicts the poet retelling the now lost Huldar saga before King Magnus VI of Norway to much acclaim. Being such a prime example of poetry as performance, Mitchell returns to the þáttr throughout Old Norse Folklore, having recourse to it in each of the book’s three sections.

Myths and Memory, the second section of Old Norse Folklore, splits its themes of myth and memory evenly across six entries, the first two of which briefly give unique interpretations to minor mythic details, one an object, the other a goddess. Originally published in Gudar på Jorden, a festschrift dedicated to Lars Lönnroth, Skirnir’s Other Journey considers the riddle associated with the creation of Gleipnir, the near-impossible bond forged to bind the cosmic wolf Fenrir. The second of these entries, originally published in the 2014 issue of Saga oc Sed, is perhaps the longest ever assessment in print of Gna, a messenger spirit associated with Frigga. Mitchell patiently goes through the slight material that is extant concerning Gna, both in saga sources and in academic literature, with the former consisting solely of Snorri Sturluson’s comment on her in the edda, and three unhelpful skaldic kenning. However, by comparing her role to similar figures, Mitchell is able to convincingly position Gna as a spirit of prophecy related to the omniscience seen in figures such as Frigga, such as those summoned in Eiriks saga rauda to attending the oracular volva Þorbjörg.

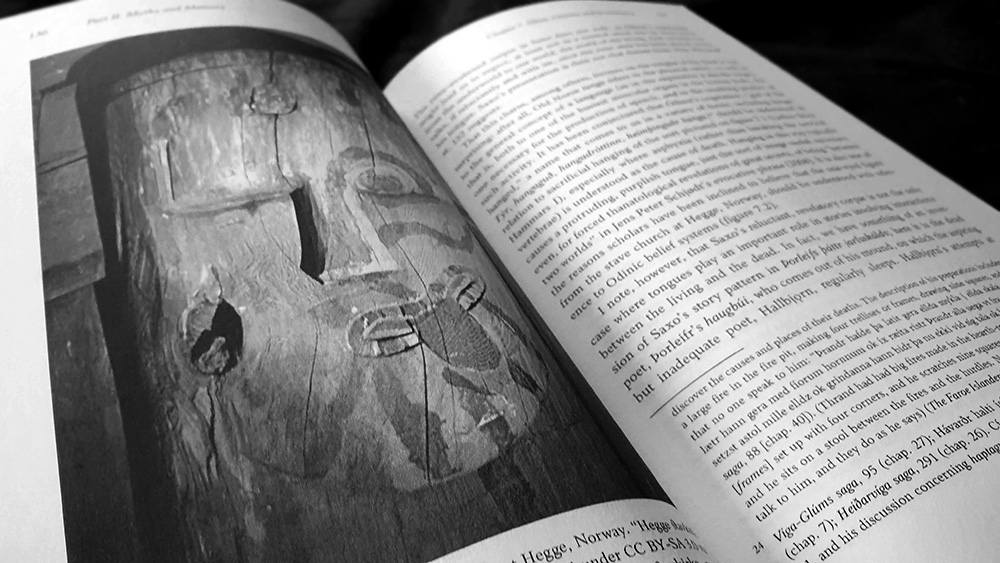

This mythonomic trinity of Myths and Memory is completed by Óðin, Charms and Necromancy, an essay that was one of the highlights in its previous appearance as part of the weighty anthology Old Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives and this remains true here, amongst these new companions. Like the consideration of Gna, the theme here is a mantic one and Mitchell looks at Óðinn’s association with necromancy, in particular his claim that he could make a dead person speak by using runes, relating it to a matrix of similar ideas of death speech from across Norse folklore and myth.

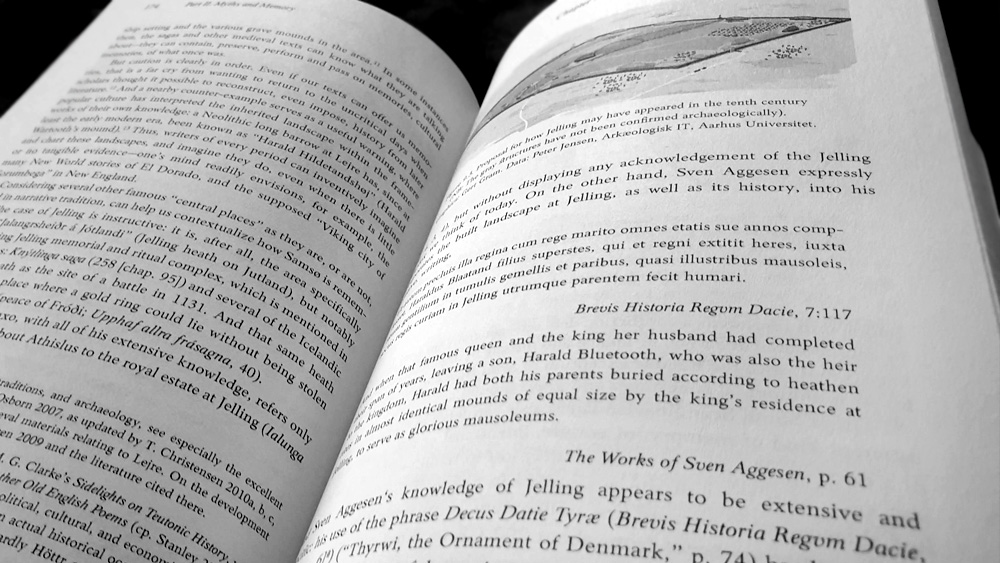

The remaining three essays in Myths and Memory move the focus to anamnesis, particularly the intersection betwixt memory and the landscape, a popular area of academic consideration in recent years. Mitchell begins broadly by considering the act of remembering in Medieval Scandinavia and how, as a phenomenon that exists between individuals, rather than inside a single person, this experience could be mediated through performance, finding particularly useful examples in the colophon to Yngvars saga vidforla and in Sturla Þórðarson’s well received performative retelling of the lost Huldar saga (as recorded in Sturlu þáttr). The other two essays in this section focus on locations, with Mitchell considering the role of memory in the collective conception of two islands: the Danish Samsø and the Swedish Gotland. Whilst Samsø has a certain charm as the site of the final battle between Hjalmar and the berserker Arngrim, and as the location where Loki accuses Óðinn of seiðr, the more intriguing of these two loci is Gotland. In an essay previously published in the book Minni and Muninn: Memory in Medieval Nordic Culture, Mitchell shows how Gotland has always attracted ideas of primacy, as a point of origin, within collective, but largely constructed, memory.

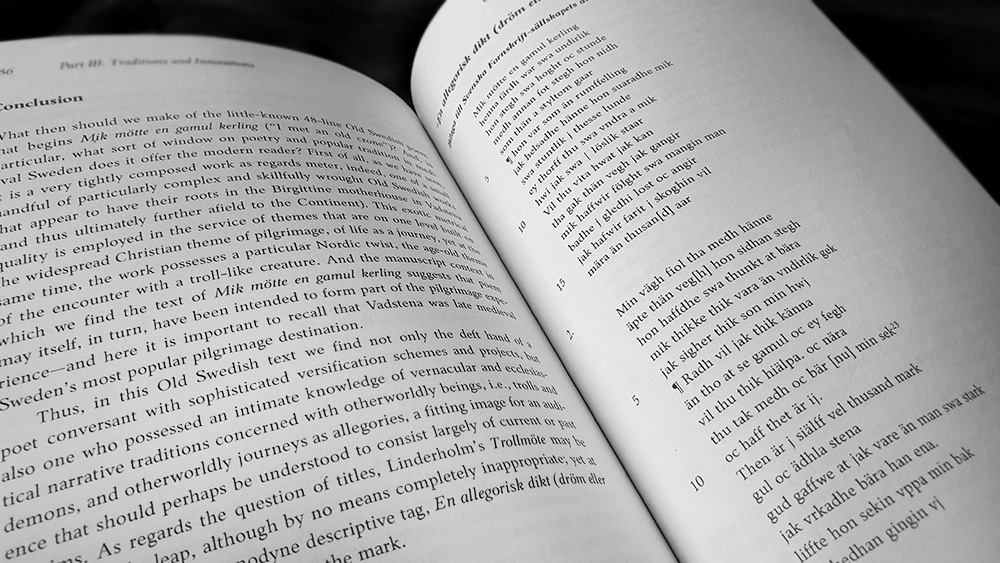

The book’s final Traditions and Innovations section features just three entries, beginning with a consideration of onomastics and the parricidal narratives of heroic tradition as conveyed through the valorised Halfs saga and Das Hildebrandslied and their historical corollary on the Listerby runestones. This section also sees Mitchell returning again to Sturla Þórðarson’s eponymous þáttr as an example of the evolution of performative Old Norse literature in Courts, Consorts and the Transformation of Medieval Scandinavian Literature. Things are then wrapped up with a brief discussion and full translation of the enigmatic Old Swedish poem known as Tröllmote (‘Troll Meeting’).

Old Norse Folklore is an immensely readable anthology, with a variety of themes that ensure there should be something for everyone. Mitchell presents his subjects with a joy, combining deft expertise with an effortless, approachable manner that nevertheless maintains an academic rigour. Old Norse Folklore has a second volume which at time of writing is to be published early 2025 and will explore medieval and early modern Nordic magic and witchcraft, in terms of syncretism, continuity, survival, as well as the reconstruction of pagan beliefs and cultic practices.

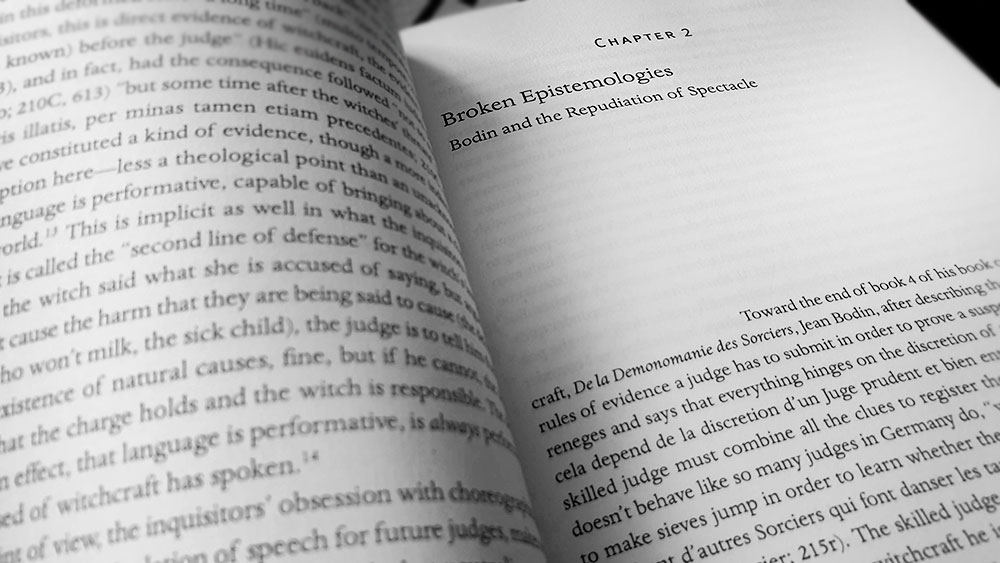

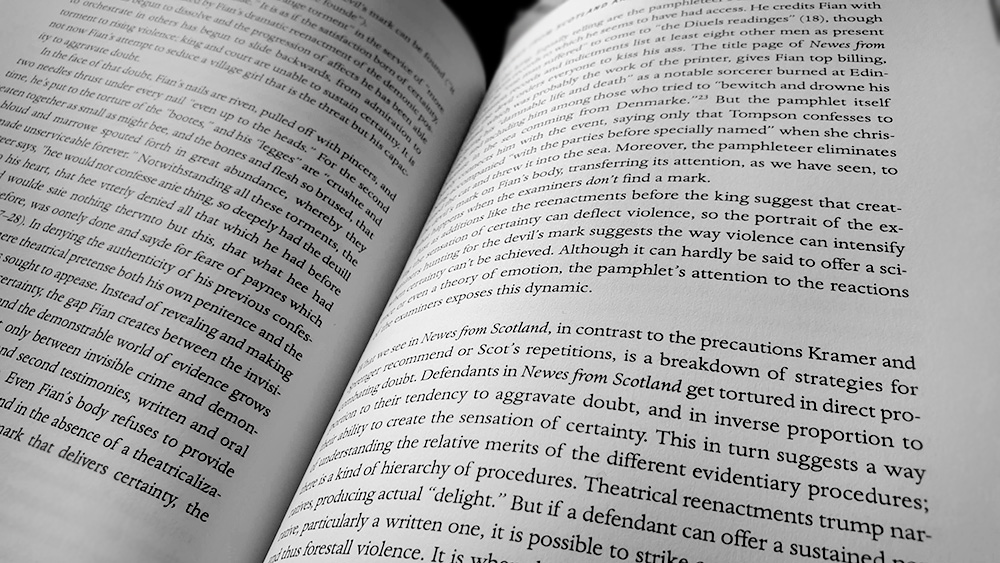

Complementing Mitchell’s clarity of prose, is the functional but beautifully formatting of Old Norse Folklore, with body copy set in a refined serif that is aided in its placement on the page by the perfect amount of airy leading and tracking, making for an effortless read. Chapter titles are rendered elegantly in a small caps version of the same face, while at the footer, bountiful footnotes receive a similar treatment to the body, all space and readability, but at a smaller point size.

Published by Cornell University Press