Subtitled A Manual of Freestyle Shamanism, Visual Magick from Jan Fries is something of a modern classic, first published in 1992 after beginning as a small treatise privately circulated amongst occultists. Despite the subtitle, there’s not a lot of explicitly shamanic content within Visual Magick, be it in the strictly etymological sense of the Tungusic word, or the core shamanism of the Michael Harner variety, or even the shamanism of new age stores, all dreamcatchers, crystals and war bonnets. Instead, if it’s core anything, Visual Magick is core Fries-brand chaos magick; apt as this was Fries’ first published work.

Subtitled A Manual of Freestyle Shamanism, Visual Magick from Jan Fries is something of a modern classic, first published in 1992 after beginning as a small treatise privately circulated amongst occultists. Despite the subtitle, there’s not a lot of explicitly shamanic content within Visual Magick, be it in the strictly etymological sense of the Tungusic word, or the core shamanism of the Michael Harner variety, or even the shamanism of new age stores, all dreamcatchers, crystals and war bonnets. Instead, if it’s core anything, Visual Magick is core Fries-brand chaos magick; apt as this was Fries’ first published work.

Visual Magick begins without preamble (save for a preface by Mike Ingalls), diving head first into the first chapter on sigil magick. This is fairly standard post-Spare sigil fare, which sounds a little unfair and dismissive, but is not intended as such. Using the analogue of a seed, Fries presents a basic but thorough guide to creation of sigils using several techniques including bindletters, automatic drawings, and magical squares. Then he offers a guide to activating and empowering them, which bleeds into the second chapter under the heading of The Ritual. In both, Fries writes in his trademark honest and conversational style, presenting the techniques matter-of-factly, listing personal preferences without prejudice but ultimately leaving things up to the reader to find what works for them. Indeed, this attitude makes ‘freestyle’ the more important word from the book’s subtitle, as it epitomises Fries’ approach: modern, eclectic, versatile, and not beholden to any historic precedent, with a touch of humour and honesty where needed.

Fries continues exploring other not particularly or obviously shamanic techniques including automatic drawing and writing, visualisations and a little bit about sex magick, primarily in its use in empowering sigils. Later he discusses creative hallucinations, zoomorphic transformation and shapeshifting, and mandalas, in which he presents a variation of his own using plant matter rather than the usual sand or paint. Throughout, Fries’ emphasis is on the pragmatic, backed up with a largely psychological model. For him, entities are just projections of the subconscious, and interactions with them are a way of accessing this deep mind. Fries does allow others the grace to believe entities to be whatever they wish, but even in this regard he ultimately comes back to the idea of them being, as part of what he calls the ‘all-self,’ ways to connect with the individual self.

This utilitarian approach means that Visual Magick often comes across as more of a self-help or motivational book, rather than a traditional magickal tome or grimoire. The argument here is that when you strip away all the artifice of magick, then that’s what you’ve got at a fundamental level: processes and a worldview that are intended to improve you as a person, give you insights, and get shit done. As a result, there’s a lot of talk of the subconscious, of perception, of analysing behavioural patterns. It’s effectively a primer that shows the science behind magick, much as chaos magick was doing at the time; though Fries does dismiss it as a then current magickal trend, despite the shared techniques and approach.

Filing under ‘some reviewers are never happy,’ long-time readers of Scriptus Recensera will know that pragmatism rules here, but Fries’ approach runs the risk of being too much of a good thing and one finds oneself longing for a touch of old fashioned occult glamour, a little mumbo? Perhaps. Jumbo? Perhaps not. Effectively, it takes some of the fun out of magick, and replaces it with the psychological model, which may have an appeal for some readers but has limited mileage with this one. With its revealing of the seams of magick, though, it does underline how anything in the book can be adapted to a more personally-satisfying paradigm and how, in the end, a ritual, a godform or an entire belief system is just something made up by someone, somewhere, sometime.

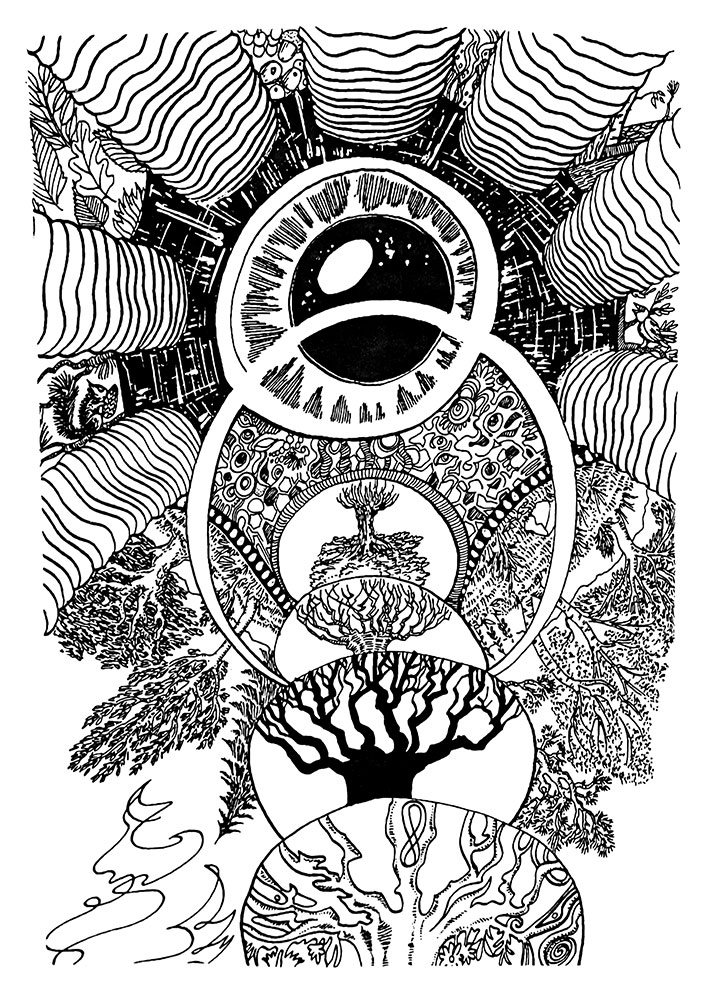

As is the case with all of his books, Visual Magick is illustrated throughout with Fries’ trademark illustrations, previous recipients of glowing commentary here at Scriptus Recensera. Atavistic line drawings combining humanoid forms and nature, they are in some way the most shamanic thing in the book, having an energy and numinosity so evocative of reaching out across worlds.

Visual Magick has the same layout styling of other Jan Fries books published by Mandrake of Oxford, meaning that it looks better than a lot of Mandrake book. It’s not necessarily amazing, but there’s a clear design hierarchy, a suitable amount of space and no glaring errors. All of Fries’ trademark illustrations are rendered crisp and clear, except for one which, by misadventure or design, is pixelated, its black lines turned jagged like a scene from an 8bit video game; which is somewhat apropos as its shaman subject looks like a hero from a 1980s side-scrolling platformer.

Published by Mandrake of Oxford.