Published in 1996 by Edred Thorsson’s own imprint Rûna Raven Press, Green Rûna is one of several variously-coloured titles that compile his previously published essays. This green incarnation, and the first in the series, draws from the 1970s to the early 1980 with material published in the Ásatrú Free Assembly’s The Runestone, the Odinic Rite’s Raven’s Banner, as well as the Rune-Gild’s own publication, Rûna, and its four volume successor, New Rûna.

Published in 1996 by Edred Thorsson’s own imprint Rûna Raven Press, Green Rûna is one of several variously-coloured titles that compile his previously published essays. This green incarnation, and the first in the series, draws from the 1970s to the early 1980 with material published in the Ásatrú Free Assembly’s The Runestone, the Odinic Rite’s Raven’s Banner, as well as the Rune-Gild’s own publication, Rûna, and its four volume successor, New Rûna.

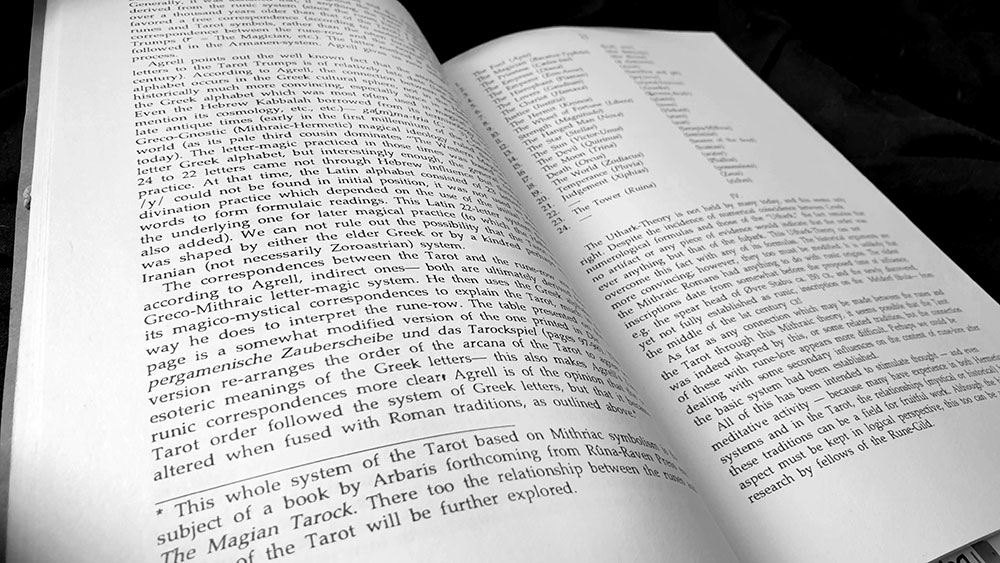

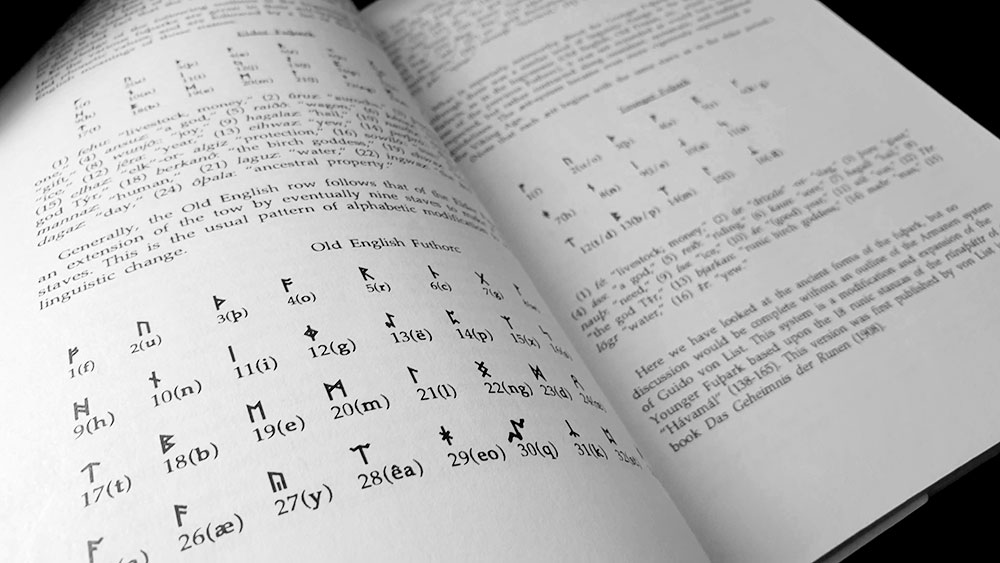

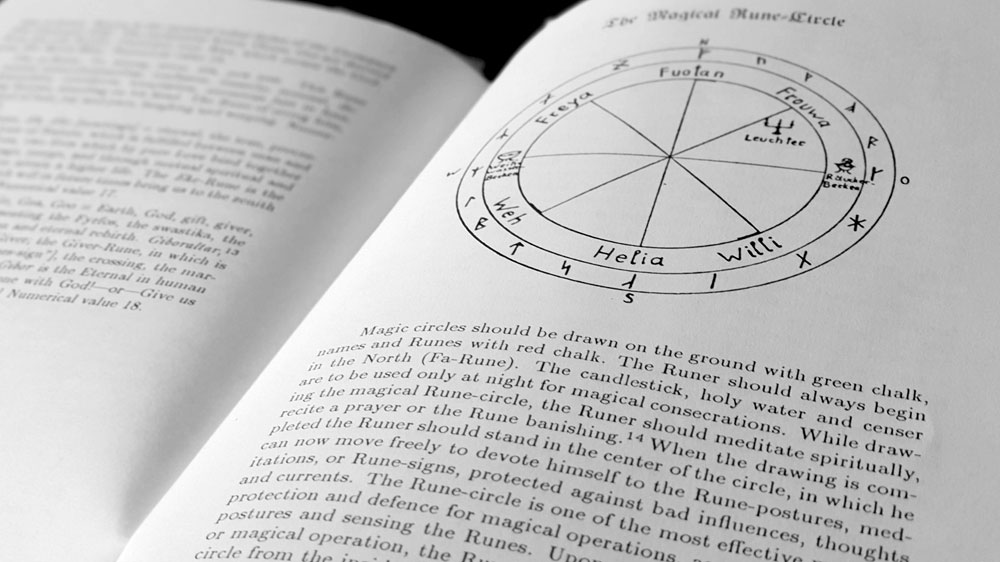

In an introduction, James A. Chisholm explains that the book’s title indicates that the material presented here is a rather unripe yet still valuable fruit. Given that many of these articles have their origin in the formative days of contemporary runic mysticism, there’s a feeling of getting in at the ground floor, with Green Rûna acting as primer containing a fair bit of entry-level material. This is grouped together in the book’s first section, Runelore, and its feels, in total, like the kind of thing that could be, and probably was, filled out and expanded into a general book on runes. There’s a brief definition of the word rune itself, and then a very 101 discussion of the futhark (Elder, Younger, Anglo-Saxon and Armanen variations), followed by a further brief article about the relative merits of each futhark in esoteric application. There’s also an article from Rûna on Sigurd Agrell’s Uthark theory, showing an early interest for his work, with an interesting footnote mentioning that an exploration of Agrell’s theory of the Mithraic origins of the tarot was at that point forthcoming from Rûna Raven Press, at that point credited to the later abandoned nom de plume Arbaris.

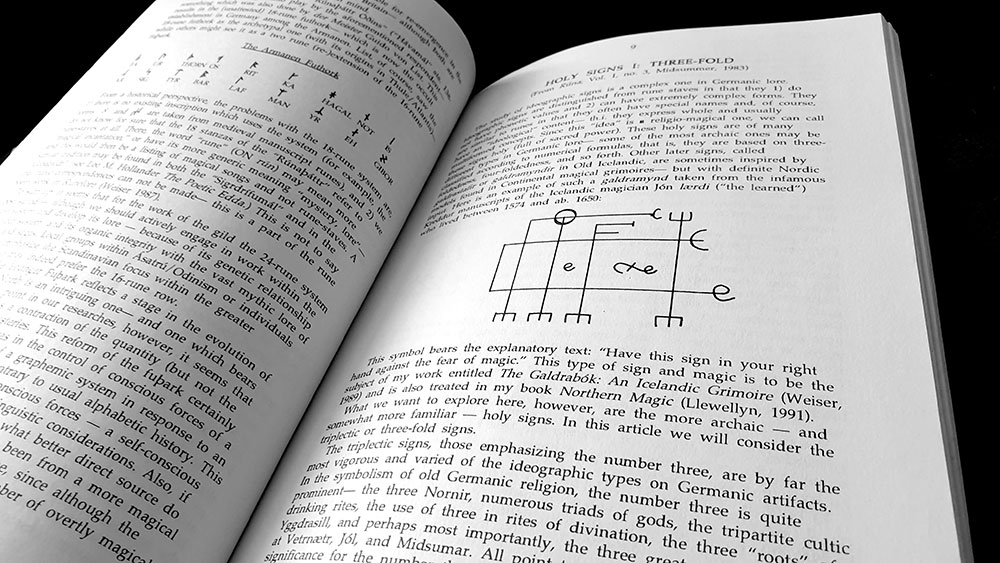

Articles on various holy signs and some brief interpretations of runestone inscriptions round out the Runelore section of Green Rûna, giving way to a section titled Germanic Studies. Considered here are more cultural and philosophical concepts, the idea of the sumble (in an article that Thorsson credits with introducing the rite to contemporary heathenism), of reincarnation in Germanic myth and legend, of definitions of the sacred, of the nature of the gods as ancestors and in a related article, the euhemerist interpretation of the gods. Two articles show Thorsson’s abiding interesting in the German runic revival with a concise survey from The Runestone of Germanic runic esotericism and from the previous issue of the same, an account of attending the reformed and refounded Armanenschaft’s Herbst Thing in 1981.

Despite the early pedigree of the material here, with Thorsson being in his sprightly twenties at the time, his editorial voice is well established and will be familiar to anyone who has read his works over the subsequent four decades. There’s that irascible, withering tone, spiced with a little hectoring outrage if something has been, he believes, misrepresented, and despite his traditionalist approach, there is also a tendency to project 20th century world views onto the past. This is particularly noticeable when the motivations of rune workers along with their belief in, and the mechanics of, the runes are attributed intent and a sophistication that almost approaches modern physics or philosophy. The runic system, for example, apparently provides a symbolic meta-language with which we can explore ourselves and the multiverse. In a similar vein is an idea that Thorsson has promoted over the years but which was already established by the time of these writings, as evidenced by an article from The Runestone called Ancient Foundations of the Rune-Cult in Europe; a title which gives a sense of what you’re in for. This describes an almost conspiratorial belief in a group of runic adepts, a rune gild that was, as he terms it, a “sacrificial Ásatrú association” which has persisted throughout centuries and continues into the modern era. Thorsson credits these runemasters with guiding the evolution of the Elder Futhark into its Younger incarnation and gives a significant amount of information about the structure of this rune gild ad perpetuum, despite there being no trace of such a frankly historically unfeasible group; effectively imagining what such a group would have been like if they had existed, but framing it like they explicitly did.

Other than the individual articles, Green Rûna includes a handful of reviews written by Thorsson for Rûna and The Runestone, providing an interesting literary timestamp and an indication of what scant titles were available then. Naturally, none of these are really esoteric titles, no contemporaries to the books Thorrson would write in the following years, with the exception of the grandmother of them all, the previously reviewed Rune Games by Marijane Osborn and Stella Longland. Instead, Thorsson looks at a grab bag of titles related to the German runic renaissance, Indo-European studies and even the Nýall philosophy of Helgi Pjeturss.

In an appendix, Green Rûna concludes as it begins, with the words of Chisholm in what amounts to a hagiography of Thorsson. The nine pages of The Awakening of a Runemaster tells the story of Thorsson’s spiritual life in a narrative that will generates sparks of recognition for anyone that has read his History of the Rune-Gild: The Reawakening of the Gild 1980-2018, as Chisholm’s text provides the basis for the first chapter of that book, expanded and embellished, but retaining many of the original phrases. The other items in this appendices are a glossary and reproductions of two Rune Gild documents: introductory information about the Outer Hall of the Rune Gild and a guide to gaining entry to the gild as of Midsummer 1990 when membership was closed to unsponsored members; and to gain said sponsorship required following the guide to runic initiation published in Thorsson’s book The Nine Doors of Midgard.

In the end, the reader can find themselves in concord with Chisholm’s assessment of the material here as unripe fruit, something that shows a clear direction of where Thorsson would go in the subsequent decades but in a nascent state. As such, it makes for an interesting historical collection, though by no means essential reading beyond this status as an archival curiosity.

Published by Rûna Raven Press