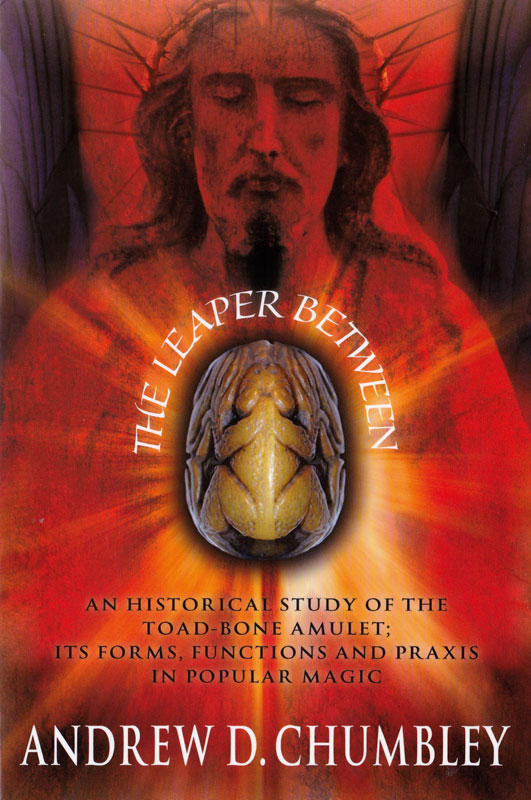

Subtitled with the suitably archaic and verbose legend “An Historical Study of the Toad-Bone Amulet; its Forms, Functions and Praxis in Popular Magic,” this small volume is an unabridged version of a study by Andrew Chumbley that first appeared in Michael Howard’s The Cauldron magazine in 2001 and has otherwise been long available online. As the subtitle indicates, this study looks at a ritual procedure in which a toad was flensed within an ant nest and then its bones set to float in a stream. When one of the bones separated itself from its companions and floated upstream, this could be caught and then used variously to control animals or as a love charm. The Leaper Between acts as something of a companion to One – The Grimoire of the Golden Toad, Chumbley’s harder to find and considerably more poetic consideration of the same theme. While that grimoire presents poetry, ritual texts and Chumbley’s personal experiences with the toad ritual, this book has a more purely historical grounding, providing an exhaustive survey of its use down through the centuries.

Subtitled with the suitably archaic and verbose legend “An Historical Study of the Toad-Bone Amulet; its Forms, Functions and Praxis in Popular Magic,” this small volume is an unabridged version of a study by Andrew Chumbley that first appeared in Michael Howard’s The Cauldron magazine in 2001 and has otherwise been long available online. As the subtitle indicates, this study looks at a ritual procedure in which a toad was flensed within an ant nest and then its bones set to float in a stream. When one of the bones separated itself from its companions and floated upstream, this could be caught and then used variously to control animals or as a love charm. The Leaper Between acts as something of a companion to One – The Grimoire of the Golden Toad, Chumbley’s harder to find and considerably more poetic consideration of the same theme. While that grimoire presents poetry, ritual texts and Chumbley’s personal experiences with the toad ritual, this book has a more purely historical grounding, providing an exhaustive survey of its use down through the centuries.

The toad ritual is first reported by the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder in his encyclopaedic Naturalis Historia, although it presumably represents a folk practice that had been extant for some time. Chumbley documents the spread of this ritual within magickal literature, dependant first on Pliny’s pivotal and well regarded work, and then, in turn, influenced by its appearance in the much later but equally pivotal Books of Occult Philosophy by the German occultist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. As with the account in Pliny’s work, the presence of the toad ritual in the books of Agrippa may have compounded an existing and extant folk practice, rather than introducing it whole cloth to local workers of magick.

In chapter three, Chumbley notes a marked change in the use of the toad ritual some time during the late 18th or early 19th century, where the procedure was increasingly used specifically as a method of magickal initiation. This change is particularly seen in East Anglian cunning-craft, but as Chumbley documents, is found in other accounts of solitary initiation into witchcraft. In this iteration of the ritual, the finding of the toadbone can cause the Devil to appear, in some cases competing for possession of the charm, and in the process, he confers on the potential witch their powers. The use of the ritual appears to have given rise to a sub-categorisation within the roles of witchcraft, with practitioners being known as Toad Witches or Toad Men. Chumbley concludes with a consideration of the intersection between the toad ritual and equine themed secret societies such as the Horseman’s Word.

The Leaper Between has been released as a trade paperback version and in two sold out hardcover editions: deluxe hardcover in full Japanese bookcloth with a gilt toad device and art paper endsheets, limited to 231 copies, and the special hardcover in full black goat with gilt toad device and deluxe hand marbled endpapers, limited to 77 copies. In its trade paperback form, The Leaper Between works out as perhaps the cheapest book ever published by Three Hands Press, although even then it’s a little expensive given the slight nature of the content and its mere 66 chapbook size pages. It’s still lovely to have the contents in the formal settings of a proper book, instead of old copies of The Cauldron or a PDF set in Times New Roman. Chumbley’s writing is, of course, very able and devoid of the flowery and esoteric verbiage found in his more mystically-orientated writing.

Published by Three Hands Press.