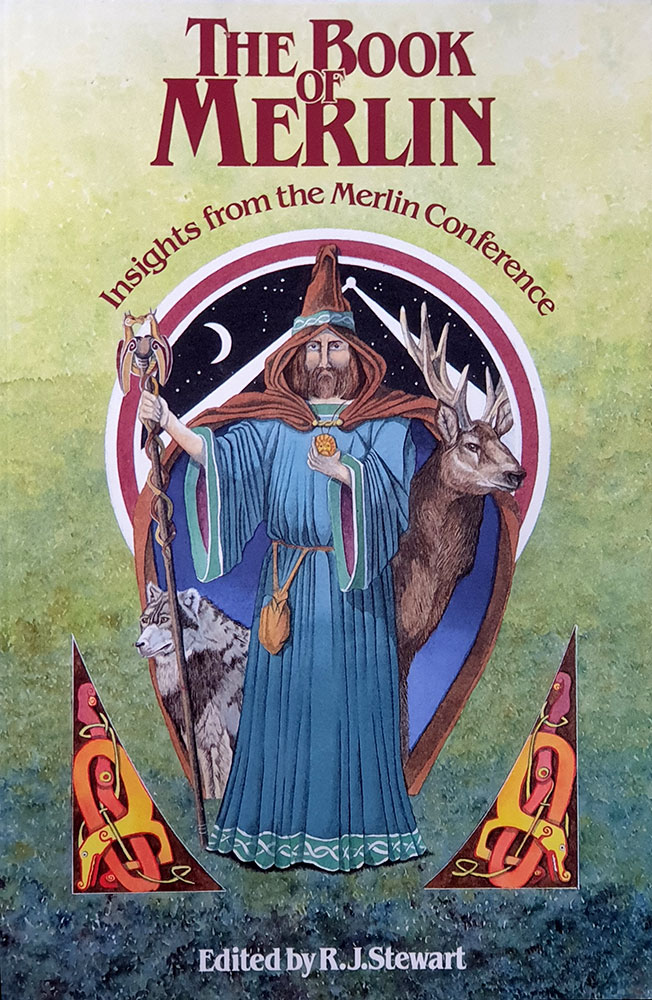

First published in 1987 and then reprinted each year from 1989 to 1991, this book primarily compiles papers from the First Merlin Conference, held in London in 1986. It’s not clear, given the use of the ‘primarily’ qualifier, whether everything included here was presented as a paper, but if it is, the rather slight line-up is quite a remarkable one, with Geoffrey Ashe, Gareth Knight, John Matthews and Bob Stewart himself providing something of a Who’s Who of mid to late 80s esoteric Arthuriana. This is part of the charm of reviewing a title like this, harking back to a simpler time where re-encountering these authors is like slipping on some old familiar shoes. This nostalgia is compounded by the delicious, oh so occult 80s/90s cover art from Miranda Gray, whose delicately-stippled and hand-coloured image of a hooded Merlin is still stunning and evocative today despite being so of its time.

First published in 1987 and then reprinted each year from 1989 to 1991, this book primarily compiles papers from the First Merlin Conference, held in London in 1986. It’s not clear, given the use of the ‘primarily’ qualifier, whether everything included here was presented as a paper, but if it is, the rather slight line-up is quite a remarkable one, with Geoffrey Ashe, Gareth Knight, John Matthews and Bob Stewart himself providing something of a Who’s Who of mid to late 80s esoteric Arthuriana. This is part of the charm of reviewing a title like this, harking back to a simpler time where re-encountering these authors is like slipping on some old familiar shoes. This nostalgia is compounded by the delicious, oh so occult 80s/90s cover art from Miranda Gray, whose delicately-stippled and hand-coloured image of a hooded Merlin is still stunning and evocative today despite being so of its time.

Things begin with an uncredited introduction that provides a brief overview of Merlin where, perhaps betraying Stewart’s authorship, there’s some typically salty invective about misconceptions surrounding him. You better not entertain the idea that Merlin is a vapid New Age pseudo-master or some doddering wizard with a star-spangled hat, otherwise, golly gosh, Stewart will hunt you down and severely castigate you.

But never fear, any vapid and New Age illusions are quickly put to rest with Geoffrey Ashe’s contribution, one of the most exhaustive here, providing a survey of Merlin’s earliest appearances, beginning with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The Prophecies of Merlin and The History of the Kings of Britain and then working backwards to the primary sources he drew from. This is a strictly factual survey of the literature, expertly corralled by Ashe, but even he can’t help adding a little mystical resonance, almost attributing sentience to the coalescence of the various proto versions of Merlin into a singular figure, identifying an “indwelling godhead” re-emerging as a powerful tutelary entity that had been there all along. I can dig it.

The content within this book is divided into five parts and the second of these takes its name from its first contribution, Gareth Knight’s The Archetype of Merlin. After an introduction by Stewart, Knight takes a not entirely focussed journey, deriving greater meaning from some of the more admittedly superficial impressions of Merlin, before exploring Gandalf as an example of the continuation of the archetype. This is just as scattershot, with Knight careening all over the place in an unendearing manner, reaching its apex when a whole page is used to quote from an editorial in The Guardian about, would you believe, the Challenger space shuttle disaster. Knight concludes this section with two other contributions, one about the blue stones Merlin is said to have brought from afar when constructing Stonehenge, and the other about the mage’s relationship with Nimuë. These are both briefer and more focused than the piece that precedes them, ending almost too abruptly where the former lingers.

The book’s third section considers Merlin’s place in modern fiction, and other than an introduction from Stewart, this is entirely John Matthews’ time to shine, with two pieces: one that gives its name to this section, followed by a two-page poem called Merlin’s Song of the Stones. As someone who has read a fair bit of contemporary Arthurian fiction all her life, this is an interesting overview, touching on some familiar notable titles such as Marian Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, Mary Stewart’s Merlin trilogy, T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone and Parke Godwin’s Firelord, as well as other less familiar ones. Matthews doesn’t spend too long on each, grouping them together into similar themes, such as Merlin being associated with Atlantis (a surprisingly popular motif), or his roles as variously prophet, trickster and teacher.

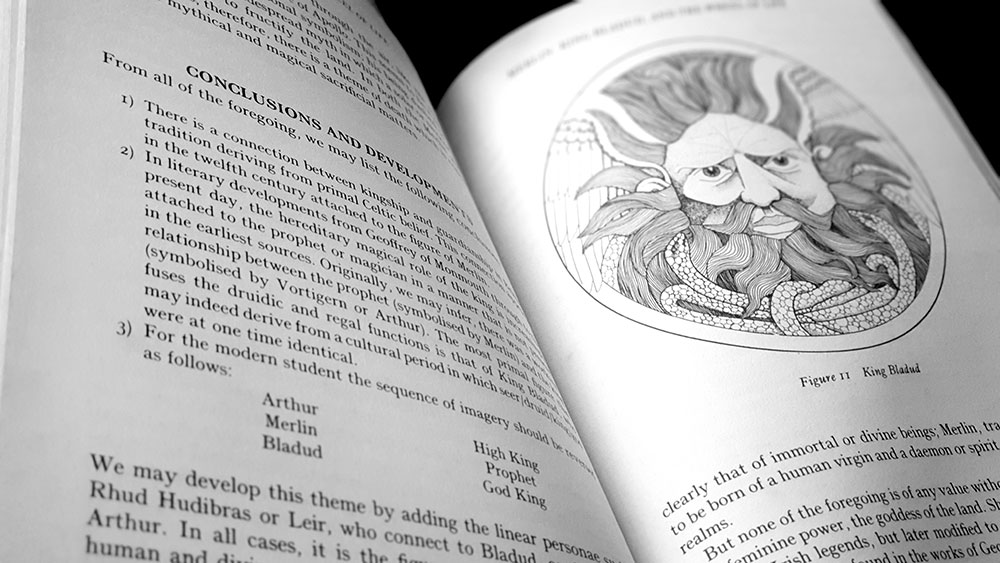

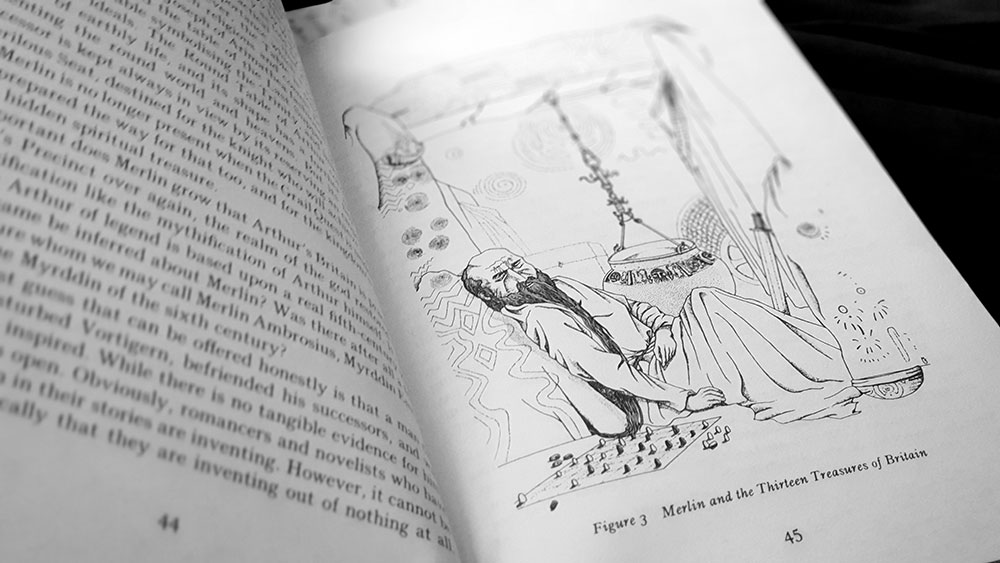

Stewart provides the final paper here, and the book’s longest, with a consideration of Merlin and the wheel of life, drawing primarily from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini in which he appears as a shamanic and prophetic wild man of the woods, passing through a seasonal round. As an adjunct to this discussion, and in an intersection with an abiding interest in the legends and mysticism surrounding Bath in south west England, Stewart also relates Merlin to a similar figure mentioned by Geoffrey in his The History of the Kings of Britain, King Bladud. Bladud is described as a worker of necromancy, a devotee of Minerva who built the therapeutic baths of Aquae Sulis, but other than appearing in Vita Merlini, there’s little connecting him with Merlin other than broad motifs, and Stewart’s attempt at a comparison seems strained if thorough.

The Book of Merlin concludes with an appendix of two primary sources, as well as a reprint of an essay from 1901 by Arthur Charles Lewis Brown concerning the figure of Barintus, the helmsman who steers Arthur to the Fortunate Isles. The first of the primary texts, introduced once again by Stewart, are extracts from Thomas Heywood’s, wait for it, The Life of Merlin, surnamed Ambrosius; his Prophecies and Predictions Interpreted, and their Truth Made Good by our English Annals: Being a Chronographical History of all the Kings and Memorable Passages of this Kingdom, from Brute to the reign of King Charles, phew. The excerpts show how Heywood can almost be described as a proto-novelist, taking the core provided by Geoffrey of Monmouth, and fleshing it out with his own take, with a particular emphasis on Merlin’s prophesies and their interpretation. The second text consists of extracts from The Birth of Merlin, a bawdy comedy probably written in whole or part by William Rowley but which in its first printing was attributed to Rowley and no less than William Shakespeare.

In all, The Book of Merlin makes an interesting if brief introduction to some ideas associated with Merlin. Given its status as documentation of a single conference, there are understandably not a lot of contributors here and the fruits that are range in appeal, with those by Ashe and Matthews being the highlights; and Stewart’s editorial voice permeating throughout. Formatting is understated but competent and in addition to her lovely cover image, Miranda Gray provides illustrations for many of the contributions, all in her trademark style of crisp, fine lines offset with a restrained use of stippled detail and shading. These are usually set against white space, with little background, all adding to their ephemeral and mystical quality.

Published by Blandford

Thank you to our supporters on Patreon especially Serifs tier patron Michael Craft.