Marking the 121st volume in Brill’s Culture and History of the Ancient Near East series since its founding in 1982, Jonathan Yogev’s The Rephaim: Sons of the Gods has a very specific focus and offers a new interpretation of the Rephaim. Best known for their enigmatic appearance in Biblical texts, where they appear as either a Nephilim-like race of giants or the spirits of the dead, references to the Rephaim are found in other ancient Near Eastern literature, from the ancient port city of Ugrat in northern Syria and Phoenician sites in North Africa. These three loci facilitate the chapter divisions for The Rephaim with Yogev giving thorough epigraphic analysis of each respective source text, concluding, where needed, with summaries and additional philological notes.

Marking the 121st volume in Brill’s Culture and History of the Ancient Near East series since its founding in 1982, Jonathan Yogev’s The Rephaim: Sons of the Gods has a very specific focus and offers a new interpretation of the Rephaim. Best known for their enigmatic appearance in Biblical texts, where they appear as either a Nephilim-like race of giants or the spirits of the dead, references to the Rephaim are found in other ancient Near Eastern literature, from the ancient port city of Ugrat in northern Syria and Phoenician sites in North Africa. These three loci facilitate the chapter divisions for The Rephaim with Yogev giving thorough epigraphic analysis of each respective source text, concluding, where needed, with summaries and additional philological notes.

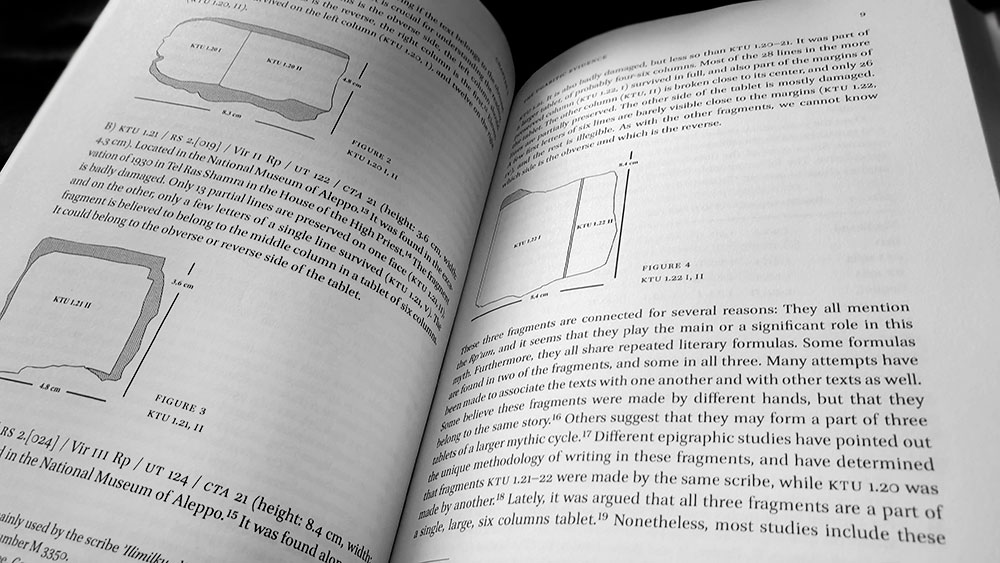

Discovered relatively recently in 1928, texts from Ugarit provide the oldest references to the Rp’um (Rephaim), all immortalised on cuneiform clay tablets in various states of completeness and legibility: The Rp’um from KTU 1.20–1.22, the Legend of Aqhatu, the Ba’alu Cycle, the story of King Kirta, a Memorial Service for Niqmaddu, a song for a New King from KTU 1.108, an Incantation from KTU 1.82, and a fragmentary text from KTU 1.166. For his translations, Yogev uses high resolution images from the University of Southern California’s Inscriptifact Project database, whilst others were obtained from private collections, or sent to him by the Louvre Museum. Transcripts were created directly from the images, comparing them to other works in order to assure as much precision as possible, referring to various opinions in cases of epigraphic and philological issues, and in instances of great uncertainty, leaving some words untranslated.

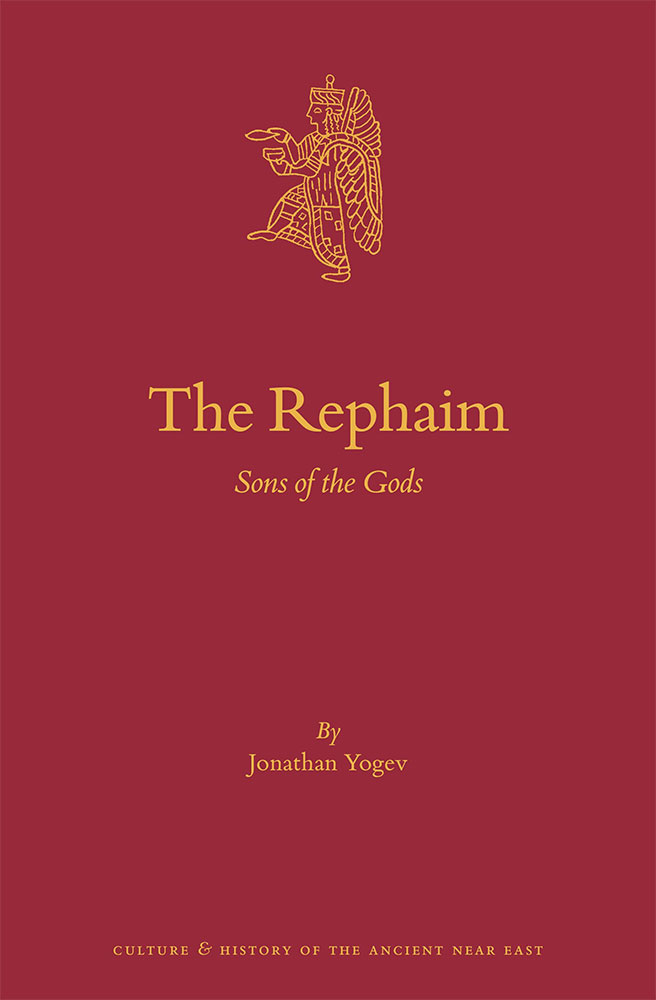

As Yogev notes later in the book, scholars first encountered the Rephaim in scripture and so the 2000 year lead-in provided by the Bible’s depictions informed subsequent interpretation of the chronologically older but only relatively recently studied Ugarit and Phoenician texts. The most obvious example of this is how the Rephaim are almost universally depicted antagonistically in the Old Testament and cast as villains of great stature. Another is the often vaunted identification with the dead. Yogev is at pains to undo these assumptions in his analysis of the Ugaritic texts wherein the Rp’um appears as mortal and material heroes and kings who ride chariots and gather together for feasts and celebration. These Rephaim may have been considered divine or semi-divine because they are referred to as ilm (‘gods’), ‘ilnym (‘divine ones’), whilst one of the named Rp’um, Kirta, is addressed as ‘son’ and ‘family’ of the ‘Ilu (the Ugaritic equivalent of El, the name for the supreme deity found across Semitic languages). At the same time, though, the Rp’um are neither immortal nor endowed with supernatural powers, instead appearing, as the Bible would phrase it, as “mighty men of old, men of renown.”

The Phoenician body of evidence is the smallest assembled here, with only two specific full length texts being considered: Tabnit and Eshmunazar Inscriptions (KAI 13 and KAI 14) and a Latin/Neo-Punic Bilingual Inscription from El-Amruni (KAI 117). Both are sarcophagus inscriptions that emphasise the association of the Rephaim with dead, and in both instances act as warnings against disturbing the occupants, lest the perpetrator be cursed in their own death and not buried with the Rp’um, This seems to affirm the idea of the Rp’um as sanctified and venerated heroes who have received an honoured place in the afterlife. One fragmentary text is also covered here, a eulogy found on a fragment of limestone from debris in the Mausoleum in El-Amruni, north of Remada, Tunisia. Written with five lines in Neo-Punic and eight in Latin, indicating its origins in the Roman empire between 1 and 3 CE, it commemorates a Romanised local farmer called Q. Apuleius Maximus Rideus. In the opening line reference is made to l’l[xx]’r’p’m which has been connected with the Rp’um due to a corresponding line in Latin that often appears on tombs as an address to the Manes, chthonic spirits of the deceased.

In the third chapter’s consideration of the evidence from scripture, Yogev makes a suitably eschatological division between the living and the dead, considering depictions of the Rephaim as the Dead (drawn from Isaiah, Psalms, Proverbs, Job and Ezekiel) as well as two distinct traditions of the Rephaim as living beings (found in Genesis and Deuteronomy for the first, and in Genesis, 2 Samuel and 1 Chronicles for the latter). Given the enigmatic and equivocal nature with which these references have engendered the Rephaim, there’s unsurprisingly very little that is conclusive in the passing mentions here. But the additional information provided by the Ugaritic and Phoenician sources provides valuable context and situates the Rephaim more clearly within the cultural milieu of the ancient Levant. Yogev highlights that whenever the Rephaim are encountered in scripture, they are either dead or in the process of being killed, recipients of a distain and hatred that can be attributed to the affront they represented to Yahwist monotheism. As the demigod descendants of a plurality of rival gods, the Rephaim were an aberration to the status of Yahweh as the only god, as was the idea that kings of other lands might claim a divine mandate due to their descent from these sons of gods. The Rephaim, then, are treated in the same way as other supernatural opponents of Yahweh, such as the monstrous Leviathan and Behemoth, defeated and consigned in their abnormity to the underworld.

One of the most interesting examples to come from scripture, and which is at odds with the prevailing Yahwist attitude towards the Rephaim, is a reference in Ezekiel to a situation in which God could send four plagues against a sinful nation, destroying all but three righteous men should they be found there: Noah, Job and Daniel. Later in an imprecation against the King of Tyre, Ezekiel mentions Daniel again and describes him as wise. Without much evidence to the contrary, it was long assumed that the Daniel referenced here was the biblical hero of the same name. Such identification ignored the temporal issue it creates for scriptural chronology, as that Daniel would have been very young at the time of Ezekiel’s prophecy with none of the fame or familiarity that his later legend would engender; making for a meaningless reference for Ezekiel’s audience and for the King of Tyre. Following the discovery of the Ugaritic texts, a different claimant to the identity of this wise Daniel was found, with the Legend of Aqhatu referring to the hero and wise judge Dan’ilu Rp’u, one of the Rephaim. Yogev argues that Dan’ilu was a heroic figure originally present in Ugaritic, Phoenician and Israelite myth, but whom, like the rest of the Rephaim, was abandoned by the Israelites as they progressed to Yahwist monotheism. Much of the details of Dan’ilu vanished, but the strength of his association with wisdom remained enough for Ezekiel to reference him as a paragon of such.

Yogev makes a fine case when presenting his argument. The Ugaritic and Phoenician exemplars are meticulously documented and the summary of the evidence is so complete, that when instances from scripture are mentioned, the broader context is clear despite the Yahwist reading. The Rephaim: Sons of the Gods runs to 180 pages for the main body, followed by an extensive bibliography, an index of subjects, and a multipage index of all the Ugaritic, Phoenician and scriptural primary texts and their catalogue numbers. Set in an eminently readable modern serif, The Rephaim is presented in a matte red hardback with a simple text and icon cover.

Published by Brill