Bearing the rather poetic subtitle of Doorways to Realms Unseen, Nigel Pennick’s The Spiritual Power of Masks promises to provide a thorough exploration of the use of masks in folklore and magic, with a particular focus, as one would expect, on the British Isles. Given Pennick’s vast experience in writing on matters of folklore and magic, one would think that he has explored masks in some depth before, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. He has certainly touched on them previously as part of his broader considerations of Norse magic and folk traditions, such as chapters on masks and mumming in his 2015 Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies, but as this book’s own Pennick-rich bibliography shows, this is the first standalone donning of such a ceremonial guise.

Bearing the rather poetic subtitle of Doorways to Realms Unseen, Nigel Pennick’s The Spiritual Power of Masks promises to provide a thorough exploration of the use of masks in folklore and magic, with a particular focus, as one would expect, on the British Isles. Given Pennick’s vast experience in writing on matters of folklore and magic, one would think that he has explored masks in some depth before, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. He has certainly touched on them previously as part of his broader considerations of Norse magic and folk traditions, such as chapters on masks and mumming in his 2015 Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies, but as this book’s own Pennick-rich bibliography shows, this is the first standalone donning of such a ceremonial guise.

As the reader begins to make their way through this, a book ostensibly about the spiritual power of masks, they may notice that while there’s a lot of spiritual power here, it’s not necessarily just about masks. Instead, masks are but one accoutrement amongst many others in what can be seen as a broader consideration of all manner of guising and ritual regalia and their use across Europe in various festivities and rituals. With this broadness also comes the opportunity to investigate the folklore that lies behind or resembles such ritualised events. Thus, there are chapters about the Furious Host and Wild Hunt, as well as other types of spectral animals, all of which tend to focus just on folklore accounts, thereby effectively providing a cultural context, rather than how they might specifically relate to guising.

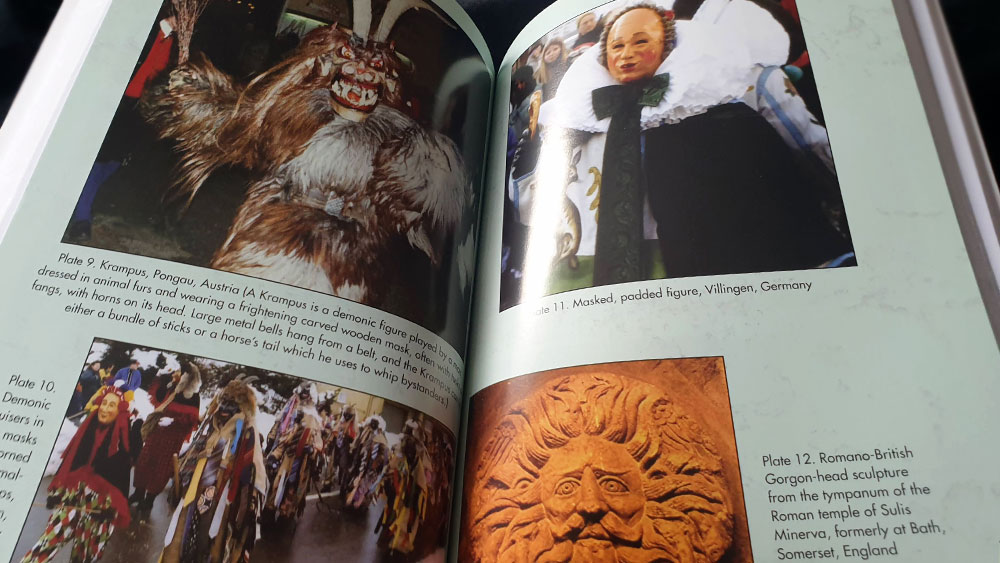

The area that receives the largest focus in The Spiritual Power of Masks are English folk customs, with Pennick offering individual but connected chapters on Straw Bears and Straw Men, Masquerades, Rural Ceremonies, Carnival Characters and Mumming; with a further chapter on the specific characters, disguises and costumes of Mummers’ Plays. Some of these entries do mention similarities with Scandinavian or Continental traditions (such as Germany in the connection to straw bears due to their greater popularity there), but by and large, the focus is on England and the wider British Isles.

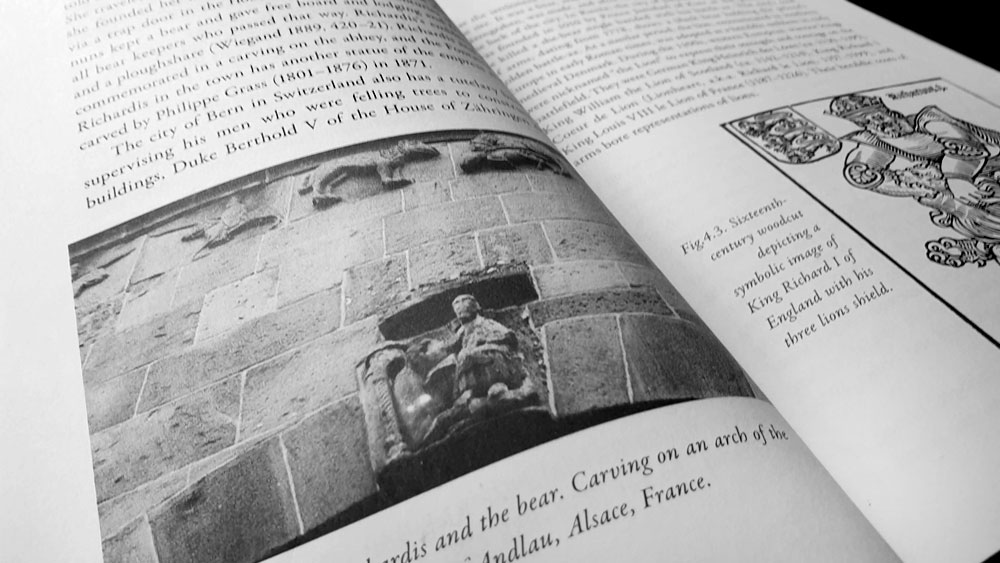

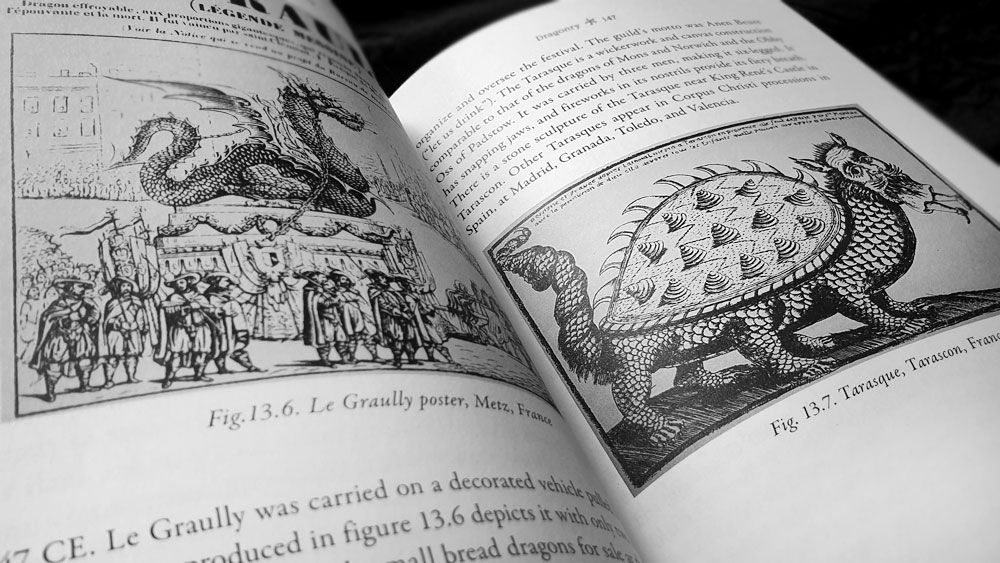

Animal guises take up significant space in this book, with several chapters devoted to their various forms. Horses have such a prominent role in guising that they warrant their own chapter, as do dragons, with Pennick listing possibly every instance of a processional horse or dragon, including a personal anecdote about performing as the white horse at a folk festival in Cambridgeshire. The miscellaneous assortment of other animal guises, those not deserving the sixteen pages given to horses or the thirteen for dragons, receive a combined chapter, so let’s hear it for the rams, bulls, goats, camels, and a few sundry others. In addition to animal kind, Pennick devotes separate chapters to their more humanoid cousins such as straw bears/men, and the civic giants that were processed through towns and cities.

The remaining chapters, constituting about half of the book, largely turn from the players to the plays, considering the various events at which guising might occur, including Christmas revels, masquerades, puppet shows, mummer’s plays, and rural festivals. Pennick tracks the history and evolution of such events, showing the influence that Commedia dell’arte in particular had throughout Europe, immortalising such figures as Harlequin, Pulcinella, Pantalone and Pierrot. By far the largest topic covered in this grouping is mumming and mummers’ plays, as well as similar rural ceremonies. Pennick is thorough here, documenting various examples from across the British Isles, all copiously illustrated.

Leaving no stone unturned, Pennick concludes with a sequence of chapters that feel slightly odds and ends, but which consider other less discussed roles of masks and guising. Of particular interest are two chapters that deal with guising as a tool for misrule, rioting and other rebellious acts, with a focus on fiery Guy Fawkes celebrations and the somewhat related creation of brigades that allowed the disguised population to fight various injustices or attempts at political or religious control. The most delightful of these were the Skeleton Army, factions of which were established across southern England, created as a reaction and opposing force to the Salvation Army’s proselytising and calls for temperance. When the Salvation Army arrived in a town, bothering the locals with excessive hymnody and objections to alcohol, the Skeletons would mobilise, meeting them with violence and vulgarity, throwing flour, rotten eggs, and dead rats. Fun times.

The strangest of these latter chapters begins with a brief description of the English festival tradition of Pantomime before veering widely across the English Channel for an only slightly longer discussion of guises and masks in modern Avant-Garde European art movements. Bauhaus, Dada, Futurism and Surrealism get brief mentions, though these receive considerably more attention than the artists mentioned in the chapter’s final paragraph where Pennick concludes by listing the names of some mask-rearing contemporary musicians you’d never expect to see receive a mention in one of his books: the Knife, Slipknot, Pussy Riot, and the veritable kings of these unexpected and aberrant appearances, the Insane Clown Posse. Just the thought of Pennick sitting there typing ICP’s name into his manuscript creates, in one, a bubble of concentrated joy.

At 267 pages of body copy alone, this is a thorough book, one that is perhaps ill-served by the limiting title, as what Pennick presents here is a valuable resource concerning guising and related folk traditions. There is so much material here, with Pennick comprehensively drawing from a variety of sources, bringing a wealth of information together in an easily accessible reference. The abundance of information can make the reader feel overwhelmed by encyclopaedic info-dumps (a previously-aired complaint in some of Pennick’s other titles), in which the facts and information are presented abruptly, with little literary or analytical cartilage to string them together. Given how frequently this critique continues to come up in these reviews, one can assume it’s not going to change any time soon. This is a shame, especially given that Pennick is a skilled writer, and just adding a bit more analysis and continuity would raise the value of these books. With that said, and while we wait in vain for anything to change. Pennick’s exhaustive data collection is for the most part fastidiously referenced, with citations appearing in-body and pointing to a lengthy reference list at the back.

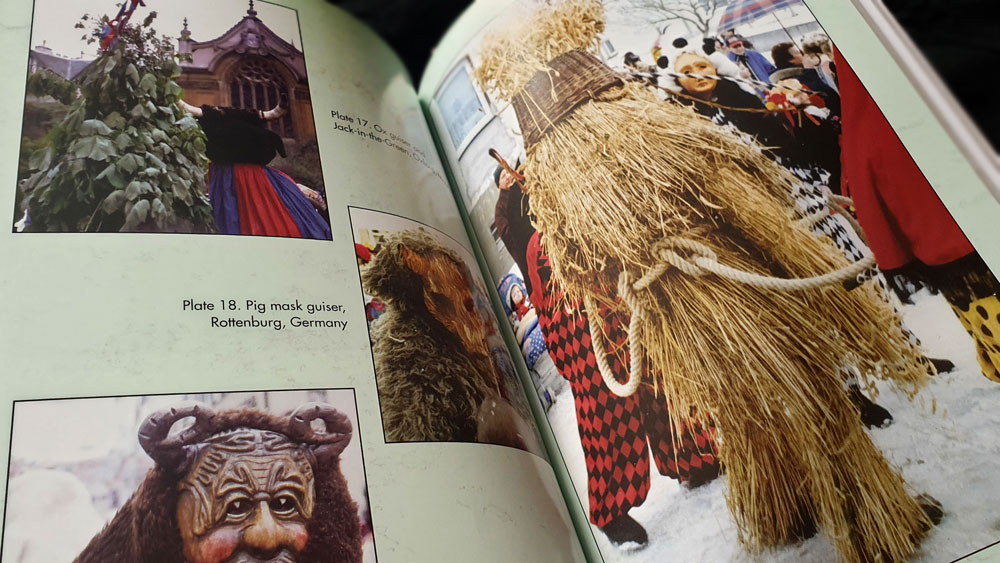

The Spiritual Power of Masks features text design and layout by Priscilla Haris Baker, using Garamond for body copy, with Belwe and Gill Sans as interior display faces, and with the decorative Amber Taste giving a vintage vibe for the cover. Like many of Pennick’s books, this one is profusely illustrated with a wide selection of photographs and other illustrations; so much so that, in some places, two-page spreads of just text can be hard to come by. This surfeit of pictures is not limited to the text body, as there is an additional 16-page section of full colour plates, doing justice to the costumes and festivities with a wonderful and welcomed burst of colour.

Published by Destiny Books