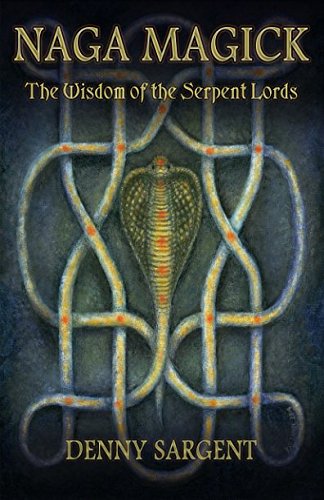

Naga Magick: The Wisdom of the Serpent Lords by Denny Sargent gets points right out of the gate for being a first as far as the theme goes. Rather than dealing with roads more travelled and their familiar pantheons, Sargent has focused on the nagas, the serpentine race of beings found in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. For contrarians and eternal rebels such as this reviewer, there’s a certain charm to this, highlighting, as it does, the cool and unknown, the adversarial and misunderstood, the allure of the darkly glamorous.

Naga Magick: The Wisdom of the Serpent Lords by Denny Sargent gets points right out of the gate for being a first as far as the theme goes. Rather than dealing with roads more travelled and their familiar pantheons, Sargent has focused on the nagas, the serpentine race of beings found in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. For contrarians and eternal rebels such as this reviewer, there’s a certain charm to this, highlighting, as it does, the cool and unknown, the adversarial and misunderstood, the allure of the darkly glamorous.

The naga are largely defined by Sargent in this manner. They are beings who seem to predate the more familiar pantheons of the Indian subcontinent, sitting in a twilight world between asuras and suras, comparable to the fey folk of Western Europe or the Orishas of Santeria. As serpent beings, the naga have associations with water and the underworld, with wisdom, healing and fertility, making them a perfect fit for those with ophidian predilections.

Naga Magick is divided into two sections: theory and praxis. In the first, and briefer, of the two Sargent gives an overview of what little is known about the naga. In a manner he himself describes as rambling, Sargent presents the naga as figures who are more familiar from folk tradition and legend, rather than grand myth. They are not necessarily the dark serpentine creatures one might expect to find within some of the more kvlt and grim areas of the occult milieu, having more of those folk characteristics that means they are to be warily respected and petitioned like the fickle fey folk of Europe.

Sargent uses the nagas to create a model of a magickal universe in which there are four Naga Dikpala, guardians of the four directions (Utarmansa Naga, Bindusara Naga, Madaka Naga, Elapatra Naga, Mahanaga), along with eight further naga lords (Anata Naga, Takshaka Naga, Vasuki Naga, Padmaka Naga, Kulika Naga, Karkotaka Naga, Sankapala Naga and Mahapadma Naga). In addition, this system’s grounding in tantra enables naga cosmology to be integrated with the concept of the Red Goddess, Shri Kundalini, and she provides the centre, the point where the eight lords converge in the naga’s underworld realm of Bhogavati. This is the union of Naga and Nagi, of Shakti and Shiva, and her veiled appearances ensures that the Red Goddess, Lalita, Tvarita Devi, Tripurasundhari, has a pivotal role in the system presented by Sargent.

When it comes to matters magickal, the central approach of the book is not a true reconstructionist one, as there doesn’t seem much to reconstruct. Sargent candidly acknowledges that there is not much that can be gleamed from historical sources in the way of naga traditions and rituals. Instead, his technique is to incorporate what little information there is into a framework that draws on established, often folk-based, traditions, with a modern Hermetic-Tantric flourish that is grounded in his experience with the Nath system of Shri Gurudev Mahendranath. Consequently, although this is by no means a Nath book, it feels as if that system inevitably informs much of what is presented here, with specific terminology, such as the euphonious ‘zonule,’ dropping in, sometimes a little incongruously here and there.

Due to this use of familiar techniques, there is a certain, well, familiarity to the magickal methods presented here. From a recognisably western perspective, the four guardian nagas each have images and seals associated with them, as well as corresponding invocations to be used in concert. A more easterly approach is found with the use of mudra, pranayama, yoga and other tools of the Naga Sadhana. All techniques converge to varying degrees in the assortment of workings and spells, culminating in a grand Naga puja. This major ritual is intended for use during the great naga festival, or for any other significant work, and is based on a Nepalese rite recorded in Jean Philippe Vogel’s 1926 Indian Serpent-lore Or The Nagas in Hindu Legend and Art (something of a fortuitous source for Sergent). This is a length rite, taking 35 pages to effectively close the book in a procedure that invokes all twelve naga, Dikpala and lords, and ultimately Shri Kundalini, with some beautifully written liturgy.

On the whole, what Sargent has presented here is a convincing, self-contained magickal system. It has a cosmology that, while not as fully fleshed out as something with a grand mythology available to it, makes the most of what information is available, and interprets it into a logical magickal paradigm. Sargent writes in something of a conversational tone, often pre-empting imagined questions from the reader, and speaking in a personal, informal manner. This helps assuage any quibbles one might have about the less than thorough or historically rigorous information in the book, with the evident caveats provided by his methods and motivations laid bare.

While Sargent, one assumes, knows his stuff when it comes to matters naga and Hindu, there’s at least one moment where the information about other cultures is a little off. He refers to the World Serpent of Germanic mythology as Surtr, which, if one was to be charitable, could be a little known, but rather appealing, esoteric interpretation, but is more likely to be just a flub. This isn’t necessarily an errant naming not picked up in proofing, as the reference is made twice. As is always the unfortunate case in situations like these, it can somewhat undermine one’s overall confidence in the book.

Published by The Original Falcon Press

Pingback: Linkage: Warding, sigils, and sex magick | Spiral Nature Magazine

What is the relationship between the Nagas and the reptilians shown to shapeshiift with humans as in the writings of David icyke?

You’d have to ask Icke that; i’m sure he’ll have some colourful answer.