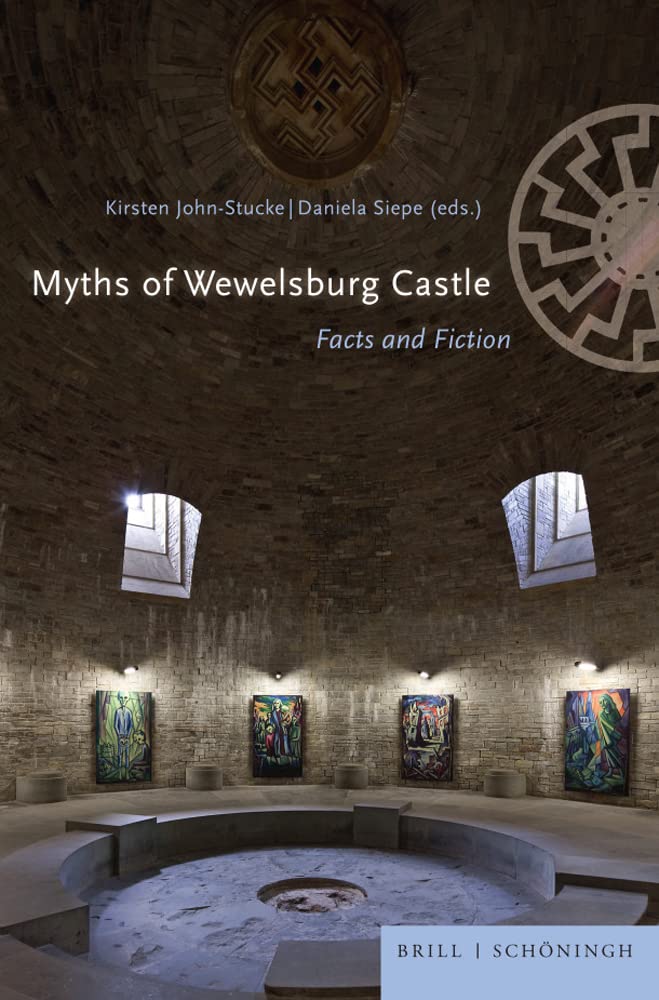

In the Landkreis of Paderborn in the northeast of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, stands Wewelsburg, a castle that dates to the seventeenth century and which gained notoriety in the aftermath of the Second World War due to its use by Heinrich Himmler as a base and school for the Schutzstaffel. To ensure its function, the castle was redesigned with décor in line with the aesthetics of the SS. Particularly evocative, and a significant factor in the enduring legacy of the schloß as a symbol of Nazi occultism, was the floor of the Obergruppenführersaal in the castle’s North Tower, into which a twelve-armed Sonnenrad (sun wheel) was set in a dark green marble. In Myths of Wewelsburg Castle, editors Kirsten John-Stucke and Daniela Siepe are joined by three other writers (Frank Huismann, Eva Kingsepp, and Thomas Pfeiffer) in presenting a variety of considerations that, for the most part, are less about the material schloß itself and instead focus on how it and the so-called Black Sun symbol in the Obergruppenführersaal have been represented in popular culture, and in occultism and right-wing conspiracy theories.

In the Landkreis of Paderborn in the northeast of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, stands Wewelsburg, a castle that dates to the seventeenth century and which gained notoriety in the aftermath of the Second World War due to its use by Heinrich Himmler as a base and school for the Schutzstaffel. To ensure its function, the castle was redesigned with décor in line with the aesthetics of the SS. Particularly evocative, and a significant factor in the enduring legacy of the schloß as a symbol of Nazi occultism, was the floor of the Obergruppenführersaal in the castle’s North Tower, into which a twelve-armed Sonnenrad (sun wheel) was set in a dark green marble. In Myths of Wewelsburg Castle, editors Kirsten John-Stucke and Daniela Siepe are joined by three other writers (Frank Huismann, Eva Kingsepp, and Thomas Pfeiffer) in presenting a variety of considerations that, for the most part, are less about the material schloß itself and instead focus on how it and the so-called Black Sun symbol in the Obergruppenführersaal have been represented in popular culture, and in occultism and right-wing conspiracy theories.

Due to the savvy sequencing of articles and a cast of just five contributors, Myths of Wewelsburg feels less like an anthology and more like a single work in which the individual authors tag in and out. There is a coherence here, and very little redundancy, which is no doubt helped by Siepe providing five of the twelve entries, and John-Stucke putting her hand to three.

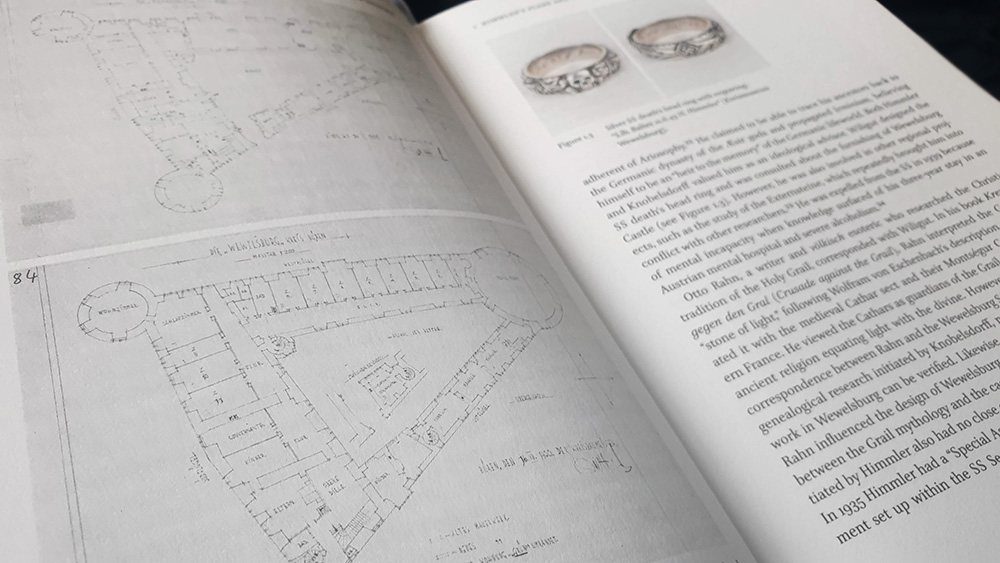

It is John-Stucke who opens the proceedings with the historical grounding of Himmler’s Plans and Activities in Wewelsburg, setting out the nuts and bolts of the schloß and its renovation during the Third Reich. Siepe follows this introduction with a triad of articles discussing the place of Wewelsburg in various forms of popular culture, beginning with the questioning The “Grail Castle” of the SS? in which she tracks the creation of legends about the schloß in scholarly and popular-science literature. This is a weighty piece, looking at how the theory that Himmler chose Wewelsburg as a grail castle developed over half a century following the Second World War, despite there being little evidence for it. Siepe is very thorough here, analysing each book in the oeuvre, tracking the accretion of ideas and how one author would build upon the other, until an almost unassailable idea emerged of Wewelsburg as a Grail Castle hosting Himmler’s new order of Teutonic Knights, and in some cases, housing the recovered grail itself. What is particularly interesting here is that many of these books are ostensibly historical, not speculative conspiracy fodder, and yet Siepe shows how unverified and often self-replicating speculation just churns through this oeuvre, adding grist to an often uncritical mill.

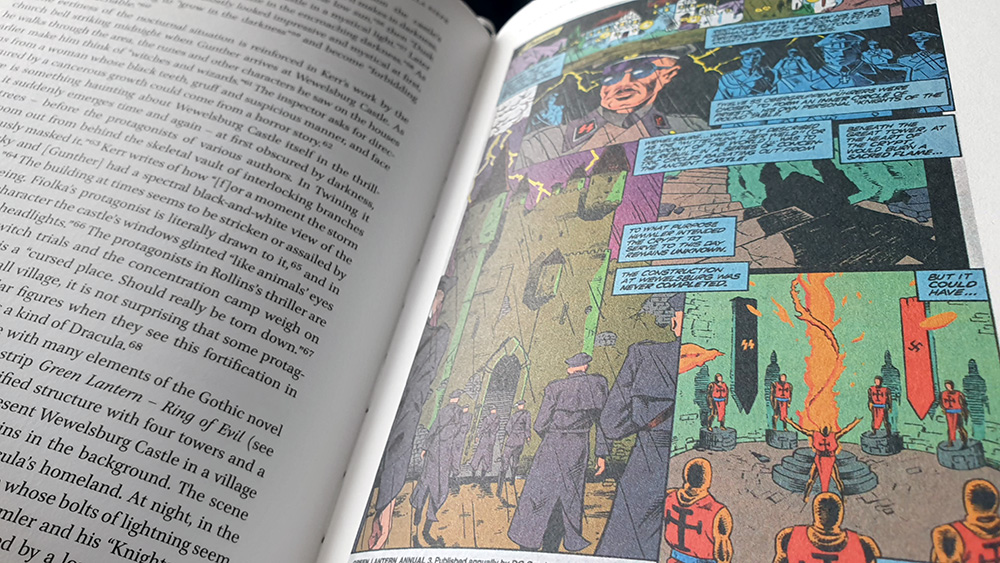

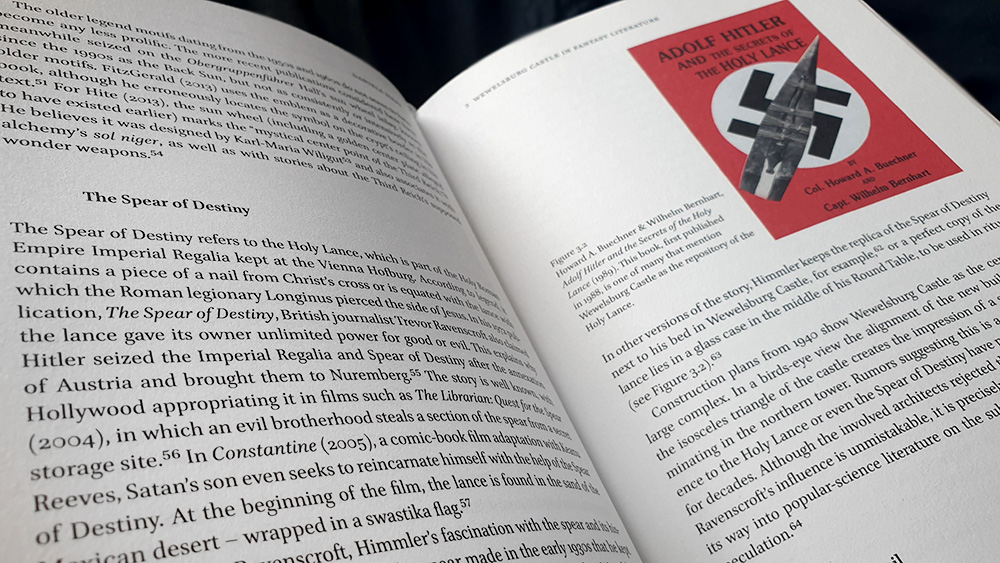

Siepe continues this vein in the next two chapters, discussing the appearance of Wewelsburg in fantasy literature for the first chapter, and in thriller novels and comics by for the second. What Siepe calls fantasy literature is not perhaps how the authors of such books would describe their work, as what is discussed here is the genre of National Socialist occult history, which is often presented as true, albeit hidden. There’s Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier’s Le Matin des magiciens, Trevor Ravenscroft’s The Spear of Destiny, and heirs like Howard Buechner (who Siepe delightfully describes as being seemingly “motivated by the pure pleasure of fabrication”). When turning to novels and comics, Siepe notes how in so many of these types of fiction, Wewelsburg and its inhabitants take on an 18th century Gothic quality, with the schloß being depicted like a looming and intimidating source of terror or intrigue, worthy of Bram Stoker or Mary Shelley. As befitting such a locus of dread atmosphere, protagonists often arrive at Wewelsburg during the night or in bad weather, with the castle exuding some unspeakable menace. This is despite Wewelsburg’s Weser Renaissance architectural style, with its ornately decorated gables, being more aristocratic than eerie, more fairy tale than fear-y tale. To match the vibe in such works, the inhabitants of the schloß invariably take on gothic roles, Himmler as a dark lord, part magician part mad scientist, with the soldiers of the SS as soulless dark knights meeting in crypts, performing rituals.

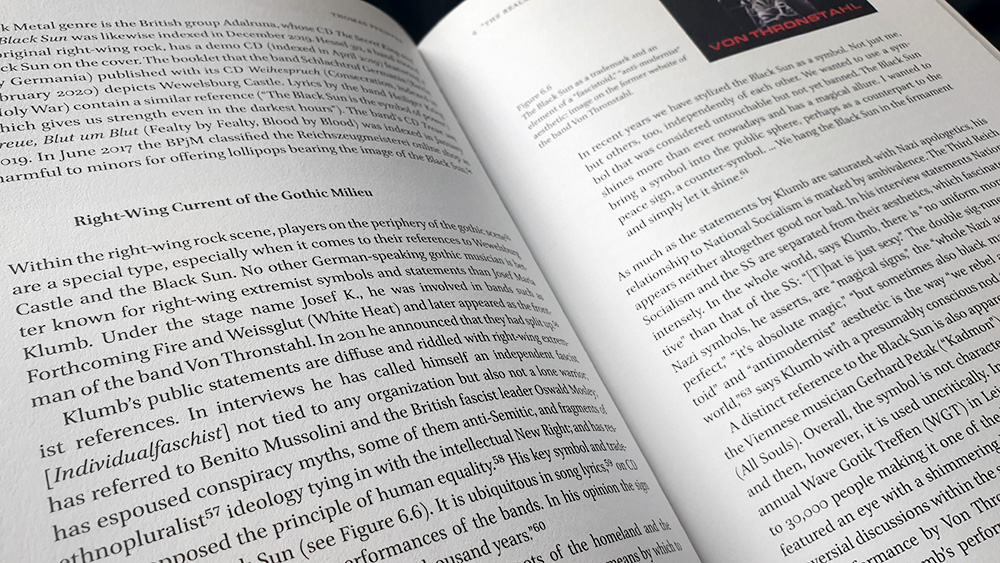

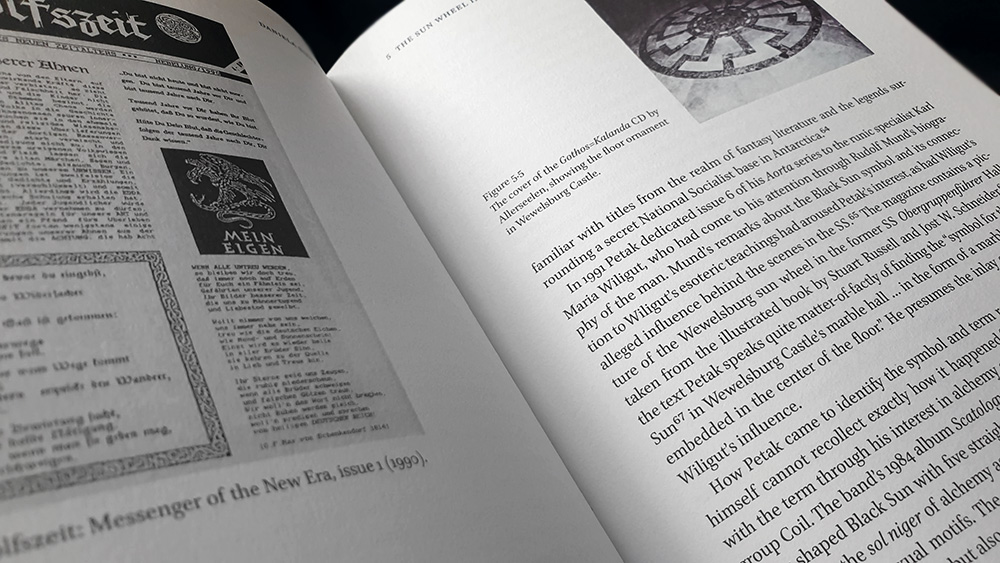

Matters now move into areas more esoteric and occult, beginning with another essay from Siepe, this time tracing the use of the so-called Black Sun floor design in the Obergruppenführer Hall; a designation that doesn’t seem to predate the end of the Second World War. Given the role of the sol niger in alchemy, and just how cool an inverted sun seems, this is an attractive association in esoteric circles, where the idea particularly flourished in the intersection betwixt speculative fiction, conspiracy theories and National Socialist remnants. Siepe gives a history of the symbol of the Black Sun as an overall concept in esoteric Hitlerism unattached to Wewelsburg, beginning with the Landig Gruppe formed in the 1950 by former Austrian Waffen-SS members Wilhelm Landig and Rudolf Mund. Incorporating ariosophical ideas from pre-Nazi völkisch movement such as Atlantis and the World Ice Theory, the Landig Gruppe developed the myth of polar Nazi survival in which the Black Sun was a mystical source of energy capable of regenerating the Aryan race. These ideas were promulgated by Landig between the 1970s and 1990s with a trilogy of Thule novels, which were then expanded upon by the pseudonymous Russell McCloud in the 1991 novel Die Schwarze Sonne von Tashi Lhunpo, in which the identification of the Black Sun with the design in the Obergruppenführer Hall was made explicit. 1991 also saw the Wewelsburg design being referred to as a Black Sun by Gerhard Petak (AKA Kadmon) of the industrial project Allerseelen in his Aorta series of esoteric chapbooks, in which he presumed its presence in the schloß could be traced to the influence of Karl Maria Wiligut. Petak was already familiar with the broader symbolism of the Black Sun from alchemy and from Coil’s 1984 album Scatology, the mention of which here does lead to the inclusion of this amusing non sequitur “The subsequent CD release of Scatology showed not only the Coil star but also a naked buttocks.” Love that indefinite article.

Thomas Pfeiffer continues this exploration of the Obergruppenführer design in The Realm of the Black Sun, here focussing on its use as a proxy identifier by contemporary Right-Wing movements in Germany (where it is not legally prohibited in the way that more direct Nazi emblems are). In tracing the use of the Black Sun in Right Wing extremism, Pfeiffer does cover some of the same territory as Siepe, particularly in regards to the Nazi Occult speculative fiction of Landig and McCloud, but most of what is discussed here are examples of its appearance amongst right wing groups and also, briefly, in neofolk and other goth-adjacent subcultures. Landig also warrants a mention in Frank Huismann’s essay Of Flying Disks and Secret Societies: Wewelsburg and the “Black Sun” in Esoteric Writings of Conspiracy Theory, as do Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, of course, and other writers such as Norbert Jürgen-Ratthofer and Ralf Ettl of the Tempelhofgesellschaft, and Chilean esoteric Hitlerist and diplomat, Miguel Serrano.

Matters of particular interest to readers of Scriptus Recensera can be found in Siepe’s Esoteric Perspectives on Wewelsburg Castle: Reception in “Satanist” Circles, where she exhaustively documents the importance given to the schloß by occultists, in particular, Michael Aquino of the Temple of Set, and Nikolas and Zeena Schreck of, well, lots of different groups at different times. Aquino was a bit of a pioneer in this regard, having written the article That Other Black Order in The Cloven Hoof whilst still a member of the Church of Satan in 1972. A decade later he visited the castle and undertook what he would call the Wewelsburg Working in the crypt, a ritual in which he called upon the powers of darkness and founded the Order of the Trapezoid, a suborder of the Temple of Set. Siepe includes a photo of Aquino standing in the crypt, something which is then echoed pages later with an image of Zeena LaVey in the same spot from 1998, taken when she, Nikolas Schreck and other then-Setians also performed a ritual in the crypt. Throughout this essay, Siepe is thorough and generous in discussing the intent of the Setians in visiting Wewelsburg, drawing on many references for a comprehensive overview where it would be so easy to simplify and scandalise. What is also of interest in this essay are briefer discussion of two lesser-known occult groups who attach some significance to Wewelsburg, both of which emerged from a German grotto of the Church of Satan: the Ruhr-based Circle of Hagalaz, and the Swiss Ariosophical-indebted Schwarzer Orden von Luzifer (founded in 1999 by Satorius of the metal bands Amon, and Helvete/Mountain King).

Eva Kingsepp follows with two essays concerned with film, the first of which, Wewelsburg Castle, Nazi-Inspired Occulture, and the Commodification of Evil, considers the spectre of returning Nazis. The two variations of this trope add a little twist to the act of Nazi recrudescence, not merely reappearing but taking on new enhanced forms: Space Nazis and Zombie Nazis; as seen in the movies Iron Sky and Outpost respectively. In her second essay, Factual Nazisploitation: Nazi Occult Documentary Films, Kingsepp gives a brief survey of the stylings of exploitative documentary films about Nazi occultism, in which she lays out common structural elements, often of the lazy and gauche type. She gives a few examples, however it’s all over too quickly, as if she’s just getting started but was called away.

Symbolic Bridges Across Countries and Continents: The “Black Sun” and Wewelsburg Castle in International Right-Wing Extremism by Thomas Pfeiffer is the final full essay here and returns to his concerns with right-wing movements. He traces the appearances of the Black Sun, noting in particular examples of violence (such as the 2019 mosque attacks in Christchurch, the attack in Halle an der Saale in the same year, and the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville), as well as its use by groups such as Chrysi Avgi in Greece, Atomwaffen Division, and the Azov Regiment in Ukraines.

In lieu of a conclusion, Myths of Wewelsburg ends with Current Tendencies Concerning the Myths of Wewelsburg Castle by Kirsten John-Stucke, which with its couple of pages mentions a few bits not covered elsewhere in what is a thorough work with something to appeal to almost everyone, whether you come to the subject from an esoteric, political, historical or conspiratorial place. Myths of Wewelsburg is a substantial volume, coming in at a little over 300 pages of quality paper stock and bound in a sturdy hardcover with a handy cloth bookmark. It is illustrated thoroughly throughout, with many of the in-body images, particular exemplars from pop culture, in full colour, making it admirably comprehensive.

Published by Brill