With its title and subtitle, Natasha Helvin’s Slavic Witchcraft: Old World Conjuring Spells & Folklore promises much in this 2019 release from Destiny Books. It’s debatable as to whether this promise is met by Helvin, a Soviet Union-born “professional rootworker and spiritual coach” who now lives in the Pacific Northwest and claims to be a fifth generation hereditary witch. That’s a lorra generations.

With its title and subtitle, Natasha Helvin’s Slavic Witchcraft: Old World Conjuring Spells & Folklore promises much in this 2019 release from Destiny Books. It’s debatable as to whether this promise is met by Helvin, a Soviet Union-born “professional rootworker and spiritual coach” who now lives in the Pacific Northwest and claims to be a fifth generation hereditary witch. That’s a lorra generations.

With her brief opening chapter, Helvin offers a general history of Russian pre-Christian belief, and its evolution with the coming of Christianity, pushing the idea of dual observance that incorporated the two. In a strange little section she also draws a somewhat unnecessary comparison with Voodoo, which she awkwardly describes as having, like Slavic paganism, aspects of the older African religions; that’s quite some cultural diffusionism.

In her second chapter, Slavic Magic, Power and Sorcery, Helvin begins with very little focus on said Slavic magic, instead presenting a primer on the mechanics of magic in general sans the book’s cultural context. This covers off many of the core principles that will be familiar to anyone who has spent time within 20th and 21st century magic, including expressing intent through actions and words, and the use of objects and amulets as repositories of this intent and power. It is only in the second half of the chapter that Helvin turns to specific Russian examples, abruptly moving away from the high magic theory to spend several pages discussing the folklore associated with Russian sorceresses. This abruptness, perhaps unintentionally, highlights a contrast in writing style that is found throughout Slavic Witchcraft but most noticeably in this chapter. For the most part, this book features the awkward, lumpen tone that one might expect from someone with English as their second language: sentences can be too short, the flow is halting and the phrasing can often be a little tortuous or naïve. The section of magical theory, however, has a more confident flow, and a contemporary nomenclature quite distinct from the rest of the book.

The spells in Slavic Witchcraft are presented with nary a trace of source or reference and in her introduction, Helvin explains that they come predominantly from her family, with others collected whilst travelling abroad and on expeditions to rural Russia. This does rob the content of context, as there’s nothing denoting a spell’s origin, nothing to give value or credibility based on provenance or even popularity, nothing to suggest that they haven’t all just been made up by Helvin on the spot. This highlights a problem found throughout Slavic Witchcraft, in which there is no referencing, no primary sources, and also, most frustrating, very little in the way of specifics. W. F. Ryan’s 500 paged The Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia this is not. Instead, this vision of Russia is an ungrounded, almost mythic, one, in which its 17.13 million kilometres contain very few named towns, cities or regions, ultimately implying a widespread homogeneity, given how so many of things are inconceivably attributed, like a comedy bit, to just “in Russia.” Apparently whether you’re in Kaliningrad or Vladivostock, it’s all the same. The same is true on matters of ethnicity and even worse, time, with the spells and the anecdotes existing in some ambiguous temporal space, unmoored from any particular time period. Context is everything and in this instance, context is completely absent. A spell may have been composed centuries ago, or it may have been made up yesterday, it’s impossible to tell.

This lack of context contributes to another problem with the spells in Slavic Witchcraft: there’s too many of them. A vast swathe of the book, fifty pages in all, is dedicated to love and relationship spells of the most psychologically suspect kind, all sharing similar goals and similar techniques to the point of redundancy. If Helvin documented where these spells came from, then there could at least be some validity to including all of them out of historical or anthropological interest. Instead, it’s just spell after spell of ways to get your husband back, how to hurt their mistress or new partner, how to forget your attachment to a married man that you’re having an affair with, how to get a reluctant partner to marry you, how to get your partner to forgive you after you’ve cheated on him and he doesn’t wanna, and how to make men who are indifferent to you instead fall for you, emotionally healthy catch that you are.

Now, books of this stripe often attract reviews on Amazon from people who, being a little susceptible to superstition, find a particular title too heavy with the bad vibes, a cursed tome that brought bad luck until they wisely disposed of it. Slavic Witchcraft itself has one of these reviews and in some ways, they’re right. Not because the book is anything more than ink on paper, or because the content is grim and dark and will open the very gates of hell (if only), but because, well, some of said content is just gross and comes from a decidedly emotionally unhealthy place. Witness spell after spell that presupposes conflict and infidelity, and provides, as its solution, coercion and deceit. And some of the spells are ridiculous in their specificity, prefacing with misogynistic scenarios that says a lot about their authors: you trusted your beloved before you got married and had complete harmony and understanding between you, but the situation changed after the wedding. You began to control him, answer his calls and demand a full report on what he was doing. The solution? Basically say a charm reminding yourself of your proper place, as the led not the lead, as the neck not the head, which, after a week’s repetition, will change your “inner state,” your anxiety will go away, your irritability will be replaced by gratitude, and best of all, your husband will once again adore you. Score!

Suffice to say, it’s all very icky and all very tiring, and all a bit strange coming from a publisher like Destiny Books/Inner Traditions whose self-help titles on relationships probably don’t contain anything resembling these psychologically damaged inanities. It’s telling that this chapter begins with a bizarre little paragraph stating baldly that God created the first humans as androgynous, happy creatures that were later divided into male and female halves, and now those unhappy heteronormative halves look to reunite with each other and that, dear reader, is what love is. Naturally, this is presented simply as fact, and it is not explained whether this is Helvin’s personal belief, some scrap of folk belief “from Russia,” or just something cut and pasted from an inspirational meme on Facebook. Helvin goes on from here, effectively justifying the spells that follow, by saying that sometimes these relationships between the two halves are not always perfect, since, she seems to say with some inevitability, “either a rival turns out to be more grasping or beautiful and takes your love away or takes a loving husband and father from his family” or you know, the fire goes out and there’s no passion. Options, we’ve got options.

The other spells collected here are grouped into sections on money and wealth, protection, and house and home. These cover many of the familiar concerns of folk medicine, with some methods that will be familiar from elsewhere. Indeed, reiterating that point, there’s often very little that distinguishes what is here from things that would be found elsewhere, with nothing obviously or uniquely Slavic about the spells. Perhaps the one selling point are the spoken charms which employ a darkly glamorous lexicon and which, par for the course, there doesn’t seem to be any prior trace of, be it in print or online, so you have no idea of their provenance, save for assuming it’s merely Helvin’s hand; or in a few cases, onemagic.ru

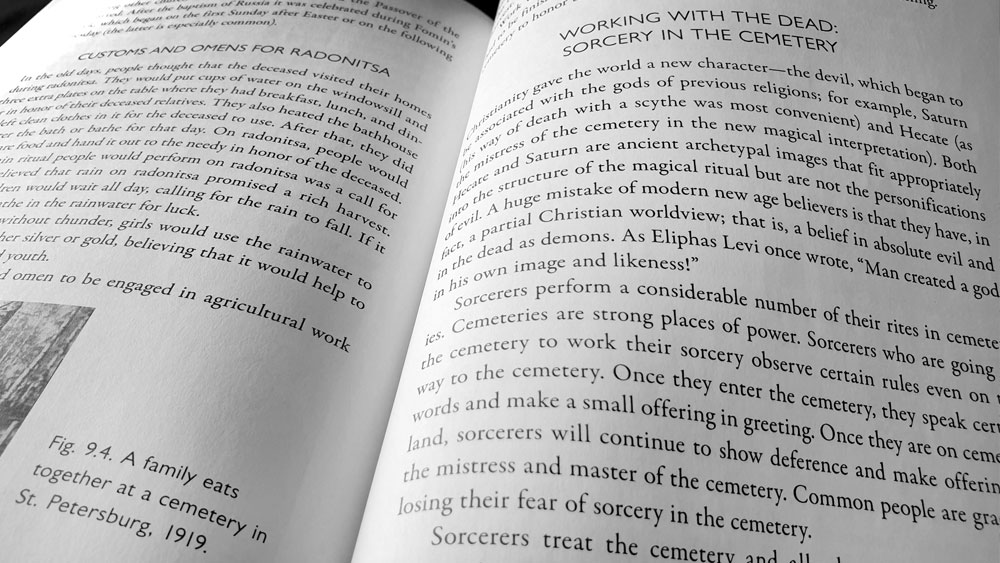

The final section of spells focuses on cemetery traditions and unlike the previous groupings, these have a substantial preamble, outlining various Slavic funeral folk traditions. Again, this has the barest of details, nothing is geographically more specific than ‘Northern Russia’ and there’s little indication of the time we’re talking about, be it ancient, recent or contemporary.

If Slavic Witchcraft documented its sources and presented itself with considerably more rigour, it would have much to recommend it, as there is a staggering amount of material here that cannot be found anywhere else. But, because of this failing, the reader, save if they be of a most trusting disposition, must surely assume that almost everything here has been crafted from whole cloth and these attested old world conjuring spells are considerably more new world.

Published by Destiny Books