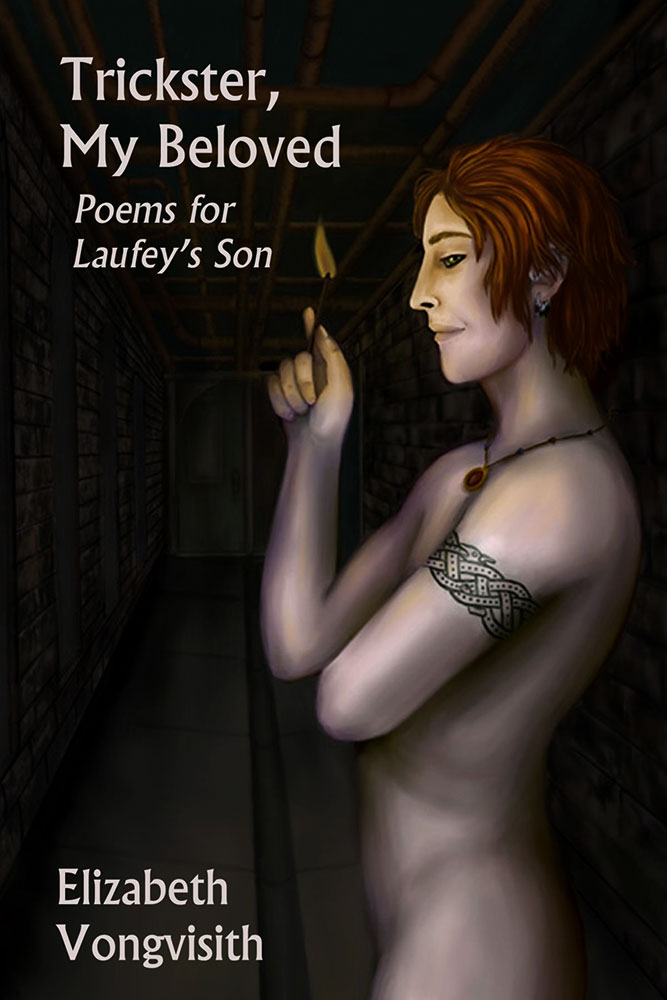

As its matronymic subtitle suggests, Trickster, My Beloved is a collection of devotional poems for Loki, written by Elizabeth Vongvisith and published by Asphodel Press. In her introduction, Vongvisith describes the book as the fulfilment of an oath, identifying works of heart, mind and hands as some of the best offerings that can be made to the gods. It is a physically slim offering at only 60 pages, but a profound one nonetheless.

As its matronymic subtitle suggests, Trickster, My Beloved is a collection of devotional poems for Loki, written by Elizabeth Vongvisith and published by Asphodel Press. In her introduction, Vongvisith describes the book as the fulfilment of an oath, identifying works of heart, mind and hands as some of the best offerings that can be made to the gods. It is a physically slim offering at only 60 pages, but a profound one nonetheless.

Published in 2006, a lot has since changed for the public view of Loki, with his profile rising dramatically, as any Marvel-tainted search results on Google, Tumblr or DeviantArt will testify. More pertinently, the Troth this month rescinded their ban on the hailing of Loki at Troth-sponsored events, suggesting a certain degree of rehabilitation for the troublesome god. The Loki in these pages doesn’t necessarily seek the kind of respectability offered by the Troth, or the fame, fanfiction and silly helmet that comes courtesy of Tom Hiddleston (had to Google to check the correct name, naturally), being instead more mercurial and capricious.

As a godwife of Loki, there’s a certain degree of intimacy in Vongvisith’s writing, which helps that air of devotional fervour. Loki is presented as a lover and constant companion, a presence whose spirit can sometimes seem almost all consuming, creating words that are redolent of the fervid depths evident in some Hindu religious devotional material. Vongvisith doesn’t shy away from Loki’s other wives, though, and has poems for both Angrboda and Sigyn. In Victory, she addresses Sigyn as her Lady of Endurance, an underappreciated figure with hidden strength and significance. Meanwhile, in Angrboda’s Lament, Vongvisith has Angrboda relate key moments of her and Loki’s interactions with the Æsir, ending each verse with a plaintive folksong-like refrain of They will take away my love, and bury him, until it concludes with the bittersweet variation They have taken my love, and buried me with him.

The sense of personal loss in Angrboda’s Lament and Victory is something of a trademark of the poems included in Trickster, My Beloved, and occurs again, in its most striking and effective manner, in The Price. Here, Vongvisith addresses Loki, describing as a seer how his children were taken from him and how the intestines of his own son were used to bind him, all drawn in heart wrenching detail that disintegrates into paroxysms of apoplectic rage.

The ties familial that are hinted at in the poems for Angrboda and Sigyn are also found elsewhere, with Vongvisith addressing other members of Loki’s family. In For the Lady of the Leafy Isle, she speaks to Loki’s mother Laufey as any daughter-in-law might, testifying to her strength and thanking her for the welcome into her house and family. Similarly, For Surt is a paean to the fire giant who here, and in other books from Asphodel Press, is identified as the foster-father of Loki. And finally, In the Dark, one of the longest poems here, describes an underworld encounter with Loki’s daughter, Hela, in language so vivid that it practically acts as a guided visualisation.

Although they are not necessarily intended as such, the clear imagery of In the Dark, or the invocatory tone of For Surt and some of the poems addressed directly to Loki, all reveal a potential for ritual or liturgical use. Words written in devotion, rather than supplication or as a wand-wielding threat, seem so much more numinous and valuable to personal practice.

Trickster, My Beloved is presented purely as text with not a single accompanying illustration, which is a slight shame, as the evocative imagery could easily have sparked a few images from any talented illustrator. One such illustrator, Milwaukee-based Grace D. Palmer, does provide the cover image, a painted image of a naked Loki, single lit match in hand, presumably about to be, in the words of the song, burning down the house. The layout follows Asphodel’s familiar style, with nothing exceptional but a still solid and functional look.

Published by Asphodel Press