Here at Scriptus Recensera we have reviewed a number of books from the early 20th century Germanic runic revival, all translated by Stephen E. Flowers/Edred Thorsson. Now we turn to a work from arguably the granddaddy of them all, Austria’s Guido von List. List is pivotal to the runic revival because it was his system of Armanen runes (revealed to him during an eleven month period of temporary blindness), rather than the conventional Elder or Younger futharks, that came to dominate German runology. In addition to being adopted by most subsequent runologists of the period, the Armanen futhark became, according to Flowers, almost ‘traditional’ in the circles of German-speaking runic magic.

Here at Scriptus Recensera we have reviewed a number of books from the early 20th century Germanic runic revival, all translated by Stephen E. Flowers/Edred Thorsson. Now we turn to a work from arguably the granddaddy of them all, Austria’s Guido von List. List is pivotal to the runic revival because it was his system of Armanen runes (revealed to him during an eleven month period of temporary blindness), rather than the conventional Elder or Younger futharks, that came to dominate German runology. In addition to being adopted by most subsequent runologists of the period, the Armanen futhark became, according to Flowers, almost ‘traditional’ in the circles of German-speaking runic magic.

Das Geheimnis der Runen was originally published, as a periodical article in 1906, and then as a standalone publication in 1908. Exactly eighty years after that initial publication, this English translation by Flowers was released as The Secret of the Runes. Flowers opens the book with a substantial introduction, 40 pages in all, providing a comprehensive biography of List, as well as summaries of his system, his influences and his influence. This is a brisk, engaging read that documents List’s life in an amiable way, with Flowers conveying a fair bit of affection for Der Meister, as he calls him. Compared to the biography, the consideration of List’s influence and influencers is briefer, with the former quickly touching on key figures, including other runologists and members of the National Socialist leadership, but not delving too deeply into these. Amusingly, Flowers lists himself as a more recent example of a wearer of Listian influence, but does it by referring, with some third-person distance, to Edred Thorsson, as if he was a completely different person.

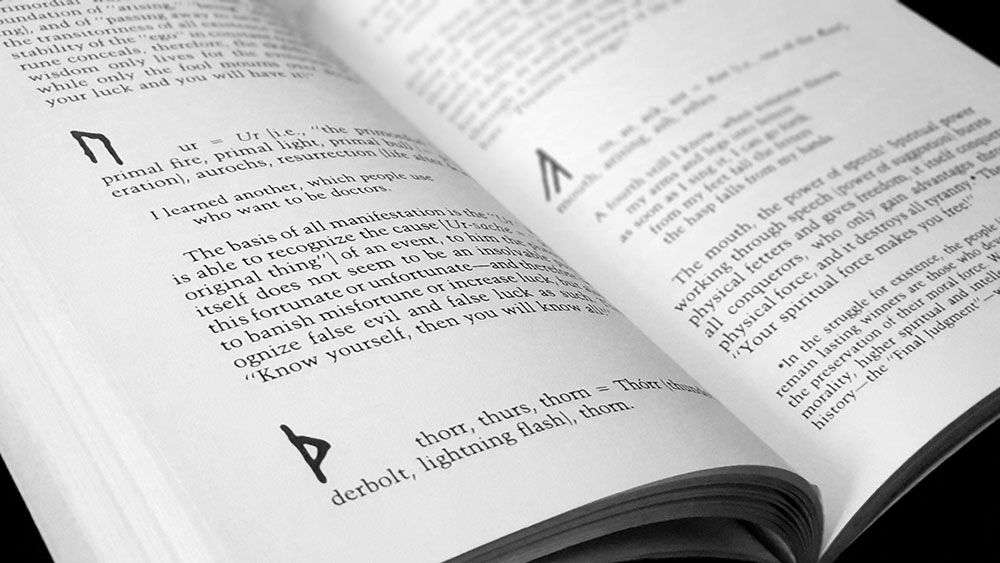

After a little introduction, Das Geheimnis der Runen proper begins with perhaps the book’s most accessible section and a now-typical listing of the runes, along with their attributes, a corresponding rune poem drawn from the Ljóðatal section of Hávamál, and a paragraph or so of explanation. While List follows convention in most cases, there are some idiosyncratic interpretations here, with Fehu, for example, being given associations with fire-generation and destruction, in addition to the usual wealth and cattle. Similarly, for Kaunaz he makes a primary interpretation of the rune as signifying the World Tree, seemingly placing greater emphasis on the somewhat incongruous sixth charm from the Ljóðatal rather than the etymology of the rune’s name.

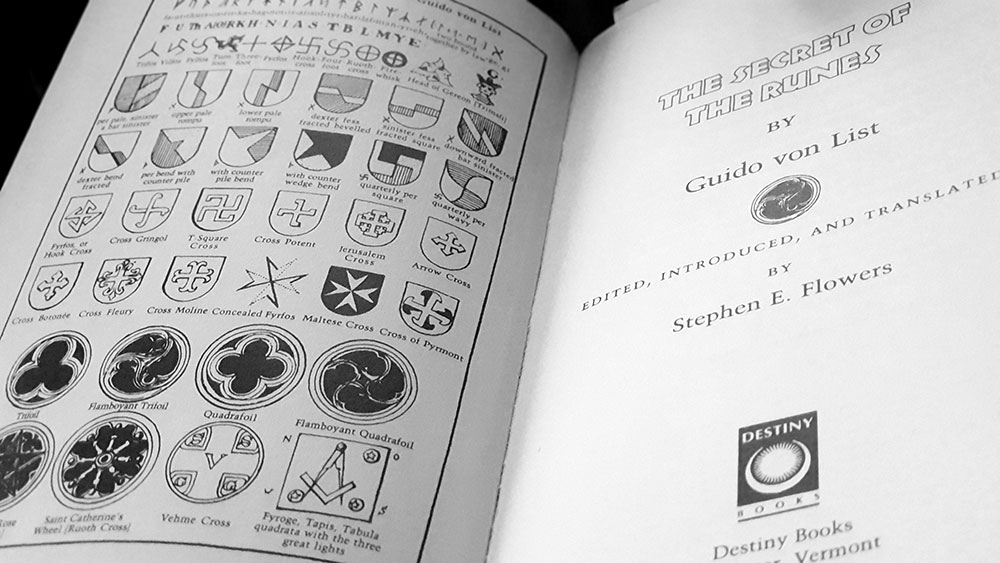

List follows his exploration of the Armanen Futharkh with an explication of his core theory in which the wisdom he was a conduit of had both a metaphysical and mundane expression. This employed a tripartite system that allowed three layers of meaning (based on the eternal cosmic law of entstehen-sein-vergehen zum neuen Entstehen/arising-being-passing away to arise anew) to be applied to almost anything, producing exoteric, esoteric and even more esoteric levels of meaning. This meant that certain Armanen principles ascended to influence Christianity, rather than be obliterated by the process of conversion, while a corresponding downward drift saw similar ideas encoded, in some manner, into folk customs. List’s particularly striking example of these is the way in which runic elements were incorporated into heraldry, not just with obvious images of runes and related symbols such as the fylfot, but even with simple geometric designs that he, at least, can discern as runeforms. In an illustration placed at the start of the book, List collects together a range of heraldic devices and shows how the simple division of the field on a shield could generate runic shapes, with, for example, a thurs rune being created with either (to use the nomenclature) a per bend with counter pile, or with a counter pile bend, or the inverted counter wedge bend. To this relatively simple device List can’t help extract (or assign) an additional symbolism perhaps never intended for four lines on a shield, seeing the first two designs as a phallic “uprising of life,” while the last in its inversion is a sunken thorn, “the death thorn.”

This section betrays the original status of Das Geheimnis der Runen as an essay because, despite its length and discursive nature, there are no chapters to break up what begins to read like a ramble. In List’s original publication, headers encapsulating the themes covered beneath them were featured on each page, but these are not included here, and without them, the length, despite the relative brevity, can feel interminable and the writing aimless. It’s why at the start List is talking about heraldry and then by the end he’s onto pastries, having passed hands, hair and breasts along the import-laden way.

Das Geheimnis der Runen is very much a book of its time. As a guide to List’s Armanen interpretation of the runes it does fine, and mileage may vary for the rest and its focuses on theory and his interpretation of folk custom and etymology. While the later provides evidence of his belief in a tripartite system that provided three layers of meaning, the linguistics don’t often ring true and seem naïve or fanciful; understandable given his dilettantish rather than rigorous involvement in the nascent field, and the way in which many of ideas were guided by his occult insights, for whatever they are worth. As always, though, given the lack of other works by List available in English, it remains an essential addition to the early 20th century runic revival section of anyone’s library.

Published by Destiny Books