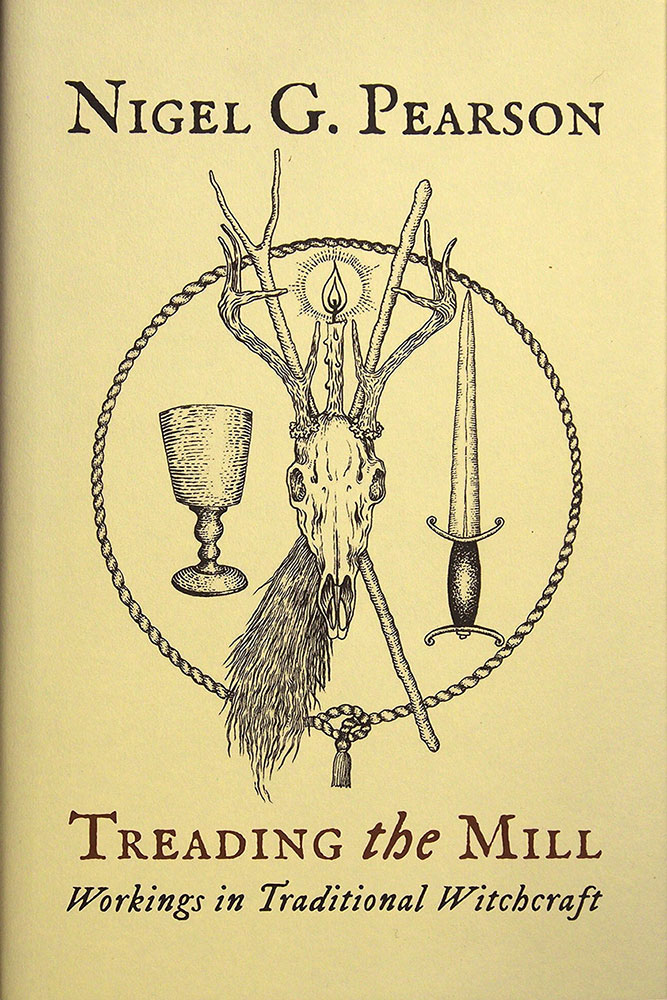

This volume from the lovely people at Troy Books is a 2016 expanded reissue of Nigel G. Pearson’s Treading the Mill – Practical Craft Working in Modern Traditional Witchcraft, a book that was originally released in 2007 by Capall Bann. With its rough-looking cover (disembodied, low opacity heads floating over a murky woodland), that particular incarnation has never moved beyond the ‘Inspired by your views’ list on Amazon, simply because yes, you really should judge a book by its cover. So, if nothing else, this Troy Books edition wins for having a lovely new cover to judge, care of the inimitable Gemma Gary.

This volume from the lovely people at Troy Books is a 2016 expanded reissue of Nigel G. Pearson’s Treading the Mill – Practical Craft Working in Modern Traditional Witchcraft, a book that was originally released in 2007 by Capall Bann. With its rough-looking cover (disembodied, low opacity heads floating over a murky woodland), that particular incarnation has never moved beyond the ‘Inspired by your views’ list on Amazon, simply because yes, you really should judge a book by its cover. So, if nothing else, this Troy Books edition wins for having a lovely new cover to judge, care of the inimitable Gemma Gary.

In the company of this new cover is a new chapter, as well as a new introduction (and the original one too), along with revised text throughout the whole book, photographic plates from Pearson, and a smattering of internal images by Gary (largely as chapter headers). In his new introduction, Pearson notes that, in a sad loss for those oenologically-inclined, he has removed a chapter on the mysteries of the cup (with accompanying guide to winemaking), which is replaced in this edition with one on the creation and use of magical incenses.

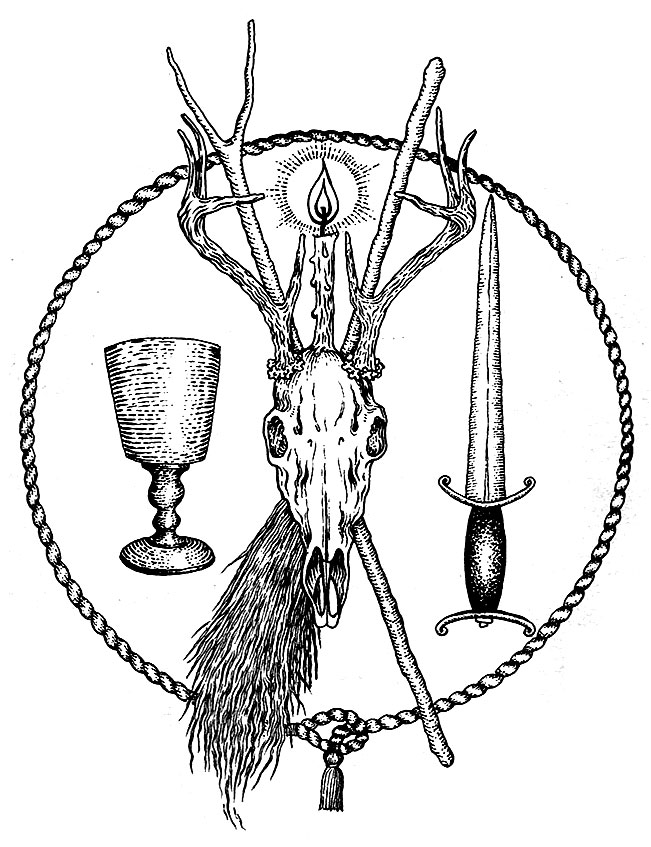

The first chapter, as one would expect, concerns the creation of space and takes that very act, hallowing the compass, as its title. It’s a broader discussion than just that one rite though, and the rubric allows for a wider consideration of the basic toolkit of Traditional Witchcraft: covering of tools, the opening and dismissing of the compass, the calling and honouring of the directions, and a closing statement and thanksgiving. As this list suggests, this hallowing of the compass incorporates many ritual elements and tools that will be familiar to anyone that has encountered entries from this milieu before, but it also includes slightly atypical elements, in particular a guided pathworking for determining individual directional correspondences.

Pearson writes effortlessly with a straightforward style that is without artifice, but which, as evidenced by the book’s 260 page length, is notably more detailed and elongated than one might expect for a title such as this. There isn’t necessarily any flab or undue verbosity to the writing, it just runs long, with Pearson taking his time to ease out points, often informally addressing the reader with hypophora; where a more concise writer might simply bullet, note it, ship it. For example, he provides two lengthy examples of procedures for compass hallowing, each filled with little asides and a conversational tone for what could easily be the driest of instructions. It’s impossible and unnecessary to attach a value judgement to this, as it is not bad writing or wrong writing, but simply the style and something for which time must be allowed when reading.

Treading the Mill, proceeds as one would expect of a title like this, covering many bases familiar, including wand creation (with a brief attendant consideration of the magical properties of various native British trees), spellcrafting (incorporating a variety of techniques under the rubric of natural magic, including herbs, potion and lotions), and the aforementioned section on incense and olfactory magic. Each of these receives a full and thorough chapter, with Pearson each time providing a little introductory theory and history, followed by broad advice, and then more specific recipes or listing of properties. It’s important to note that for all the thoroughness, Pearson doesn’t give much in the way of rituals, formulae or recipes that must be followed by rote, instead offering a general framework and enough information for the practitioner to work out their own specific approach. The reason for this may be gleaned in the prelude to the section on spellcrafting where Pearson states that the efficacy of a spell lies within the person performing it, rather than the spell itself.

The acknowledged so-called low magic of the preceding chapters then gives way to a different emphasis with Entering the Twilyte, in which the focus is not on sympathetic magic but more on transvection and others examples of travelling in spirit. Pearson makes a distinction between the spirit travelling of the Craft and the full-on possessive states of voudon, or the heightened sensations of ecstatic religions, presenting instead something with a more sedate aura, where awareness and control is maintained. Like the compass hallowing at the start, this involves a fair bit of guided pathworking and visualisation, which Pearson acknowledges is looked down upon by some traditional witches but which is, he says, just “good old-fashioned Witch magic” that has been part of his own training, and used by other traditional crafters, past and present. And for those who think they are unable to visualise anything, he’s got one word for you: “piffle.”

The final two chapters of Treading the Mill turn to the beings encountered, first with what are defined as spirits, and then with the powers or gods. Spirits is a broad definition that runs from environmental genii locorum such as land wights and sea spirits, to familiars and fetches, all the way to the Almighty Dead and the Elven and Faerie Folk. Pearson provides a veritable bestiary of these various creatures, and for some, includes ways of working with them: a rite for communing with your fetch, or a guided pathworking to visit the ancestors, for example.

For the gods, Pearson makes the point straight out of the gate that traditional witchcraft is not a nature-based fertility religion like its ignominious sibling Wicca, and so the gods of this system, while having associations with nature and the land, are seen as more cosmic forces that, to render it poetically, “have their being in the realms of the stars and the dark space beyond and between them.” These deities are not given names in this system (though Pearson acknowledges that they have analogues in some mythologies and that those names are used by some practitioners), but instead have broad titles that describe their roles. For the male there are the King of the Wildwood, the Lord of the Mound, and the Master of Light, while the female is the Witch Goddess who is both the Great Queen and the Black Goddess. For each of these, Pearson provides a thorough description, along with little rites and workings for connecting with them.

While inevitably there’s not a lot of revelations in Treading the Mill, with it covering territory that multiple authors have explored (and will continue to do so), Pearson presents it all as a cohesive, internally consistent system. His thoroughness, while making it longer than other such tomes, works to its advantage, giving the reader a carefully considered and complete window into this version of traditional craft.

There’s a comforting weight to Treading the Mill, with its 260 pages on a nice 90gsm stock, bound with solid coverboards. The formatting within adds to that feeling of stability, with its deft and confident layout, providing nothing sensational but rather a clear and clean look with just the right amount of witchy archaisms. It is this, and the content itself, that makes Treading the Mill sit effortlessly on the shelf in the company of other Troy Book titles from the likes of Gemma Gary and Corinne Boyer, with its scrappy Capall Bann beginnings all but forgotten.

As with many titles from Troy Books, Treading the Mill is available in a multitude of formats, from, at one end of the economic scale, a paperback edition with a gloss laminate, to, at the other, a fine edition of 15 hand bound examples in red goat leather with gold foil blocking to the front and spine, housed in a fully lined black library buckram slip-case, blind embossed to the front. In the middle range of affordability and availability is the standard hardback edition with red endpapers, bound in black with gold foil blocking on the spine, and wrapped in a buttermilk 120gsm matt dust jacket. A now sold out special edition of 250 hand-numbered copies was bound in black recycled leather fibres, with gold foil blocking to the front and spine, and red endpapers and head and tail bands. Finally, there’s the patented Troy Books Black Edition version: a limited hand-numbered edition of 250 in Royal format, 234 x 156mm, bound in black recycled leather fibres, with black foil blocking to the front and spine.

Published by Troy Books