The work of Corinne Boyer has been reviewed here before at Scriptus Recensera in the form of her Plants of the Devil, published in 2017 by Three Hands Press. This larger volume from the previous year follows the same arboreal and botanical avenues inherent within that later work and while Plants of the Devil was a relatively slight work with something of, as its title intimated, a diabolical focus, Under the Witching Tree is a far weightier tome, aiming for thoroughness and living up to its descriptive subtitle of being A Folk Grimoire of Tree Lore and Practicum. Under the Witching Tree is also the first volume in a three part trilogy from Boyer, with the second instalment focusing on herbs released in 2019.

The work of Corinne Boyer has been reviewed here before at Scriptus Recensera in the form of her Plants of the Devil, published in 2017 by Three Hands Press. This larger volume from the previous year follows the same arboreal and botanical avenues inherent within that later work and while Plants of the Devil was a relatively slight work with something of, as its title intimated, a diabolical focus, Under the Witching Tree is a far weightier tome, aiming for thoroughness and living up to its descriptive subtitle of being A Folk Grimoire of Tree Lore and Practicum. Under the Witching Tree is also the first volume in a three part trilogy from Boyer, with the second instalment focusing on herbs released in 2019.

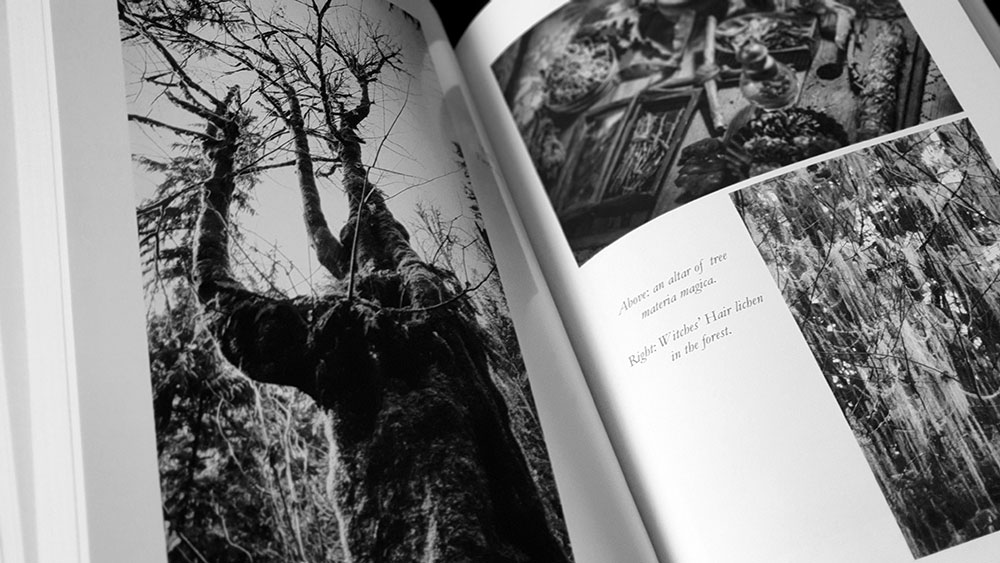

In fulfilment of its brief as a tree grimoire, Under the Witching Tree is divided into unnumbered chapters focusing on each of the twenty trees: elder, hazel, rowan, apple, walnut, yew, pine, holly, spruce, western red cedar, birch, willow, alder, blackthorn, aspen, hawthorn, oak, ash, linden and maple. The trees are organised within a seasonal framework, providing something of a theme for each quarter: the black earth medicines of autumn, an altar of winter charms, a springtime forest rite, and the deer sorceress of midsummer.

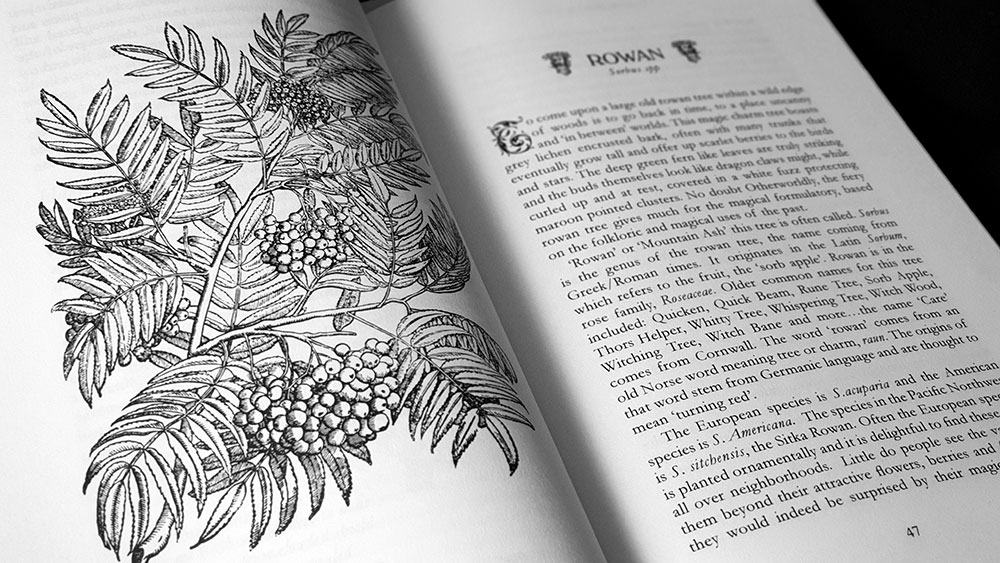

As suggested by the book’s 288 page length, the considerations of each of these twenty trees are dense and thorough, beginning with a comprehensive outline and description of each tree and its folk associations, followed by examples of practical use, some drawn from Boyer’s specific personal practice, others from existing folk rituals and recipes. Each description begins picturesquely, with Boyer wonderfully setting the scene by placing the tree in its environs, the brittle boned elder tree in a forgotten meadow, dim shadows creeping during twilight hours beneath the branches of a walnut tree, and the birch as the White Lady of the forest, gleaming in the moonlight.

These are then followed by the listings of various folk beliefs associated with each plant, but in contrast with the introductory word paintings, these are unfortunately presented in a rather less pleasing manner. Instead, the entries have something of the quality of the info dump about them, with long paragraphs that are comprised of short sentences that jump abruptly from one fact to the other, usually without any transitional phrases to tie them together, often creating fragments and non sequiturs that make the reading a slog. As such, the content resembles the encyclopaedic nature of studies of folk practices by Grimm or Frazer, where loquaciousness loses out to the pure documenting of fact and anecdote; though the difference between those works and this is the lack of referencing. With the amount of info being dumped here, it would admittedly have made for a messy layout to have everything cited with footnotes within the main body, but other than guessing or some judicious Googling, there’s no way to know where exactly each fact comes from; despite there being a bibliography at the end. There is the occasional aberrant and inconsistently treated in-body citing of a source, whether it’s mentioning the title of a work, or in one case, listing it as a full in-text citation with title/author/date, but this simply draws attention to the considerably more numerous moments in which sources remain uncredited. Why those ones, but not these ones? This becomes particularly important when obscure little gems of knowledge are mentioned and you’d love to know more; or conversely, when you wonder where boldly-stated but potentially spurious facts have come from – I’m looking at you, Odin’s sacred hazel wand, decorated with reddened runes.

The reason for this lack of referencing appears to be that large sections of information are sometimes taken uncritically from equally citation-deficient sources, with many of the entries on hazel, as one example, coming from Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants by Claudia Müller-Ebeling, Christian Rätsch and Wolf-Dieter Storl (including that claim about Odin’s hazel wand). Like Under the Witching here, Storl’s section of Witchcraft Medicine has the same sense of unreferenced and unedited notes, cast ‘pon the page, devoid of any of the conventions of narrative or structure.

Inevitably, given the simplification that occurs when paraphrasing someone else’s citation-free information, errors or lack of clarity are introduced as the material moves further and further away from the source with each translation. An ambiguous Wikipedia summary of scholarly speculation by Turville-Petre (in his Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia) that Thor’s wife Sif may have once been conceived of as a rowan tree (given the keening of the rowan as ‘the salvation of Thor’) is transformed into a definitive statement of belief for Germanic people (with the usage of ‘conceived’ misread), in which Sif now “was thought to be conceived in the form of the rowan tree.” In another case, a contemporary alchemist who is quoted by name in the Müller-Ebeling/Rätsch/Storl book becomes simply an anonymous “German alchemist,” making both he and his statement devoid of any authority and set adrift in the unspecified byways of history and time.

This isn’t to say that the information presented here is riddled with errors, just that it’s impossible to tell either way, as so many of the facts are shorn of their context, whether it be their original source, or their actual provenance in time and space. As such, the cavalcade of historical anecdotes can be read as giving a broad impression of the associations a particular tree might have, but you would want to dig a little further before taking anything presented here as botanical or anthropological gospel.

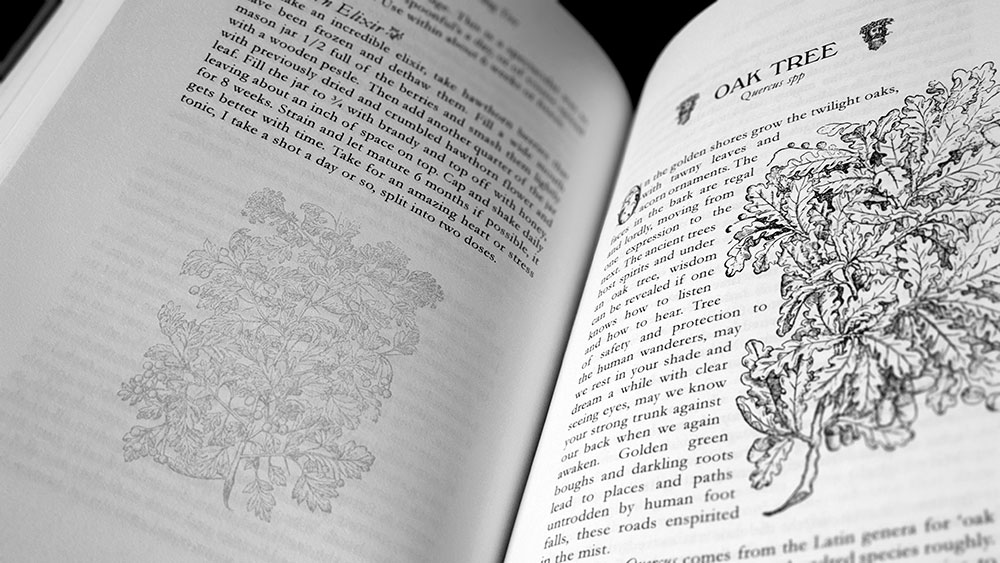

The entries for each plant are formatted to begin on the recto side of the page spread, and are usually preceded by the plant’s botanical illustration, printed at full page size, on the verso side; save for rarer cases where no space on the verso means they are instead placed as smaller, in-body images on the recto side, with the text wrapping around them. These images come from a variety of, one assumes, public domain sources, and so are not consistent in weight or style, with some appearing particularly heavy in line compared to others. But, unlike similar situations in lesser books, each image is of acceptable quality, with no pixilation or compression artefacts. A few appear to have been vector-traced, but otherwise most are sharp and clear in their original raster lines. Where needed, these images are reused as space fillers at the end of each plant’s entry, where they are scaled down, somewhat inexplicably flipped horizontally, and printed at a lowered opacity, looking less a valid stylistic choice and more like the printer ran out of ink.

Given the amount of information crammed into these entries as brief sentences, the consideration of each plant can run quite long, with the basic introduction for each coming in at an average of five pages, followed by several more pages for sections on their use in folk medicine, several paragraphs on how they can be employed in general personal practice, and a handful of more specific recipes. The recipes run the gamut from drinks and ointments to charms, incense and talismans.

Under the Witching Tree concludes with a set of appendices as thorough as the main content, seven in all, covering some of the more technical aspects of the practical applications offered throughout the book: storing plant material, creating ointments, drinks and elixirs, rendering fat as a base. This is a good way to do it, rather than cluttering up each individual section with repetitive instructions.

Under the Witching Tree runs to 280 234 x 156mm pages with twenty black and white photo plates, in four editions: a paperback with a gloss laminated cover, a standard hardback, a special edition, and a fine edition. As is common with Troy Books titles, the standard hardback edition feels as good as a special edition with its ruby-red case binding, gold foil blocking of title and rowan sigil to the front and title on the spine, green endpapers and green head and tail bands. The special edition of 300 hand-numbered exemplars, swaps out the red of the cloth for a dark green one, with the foil now blocked in red, and red head and tail bands. The now sold-out fine edition, housed in a fully lined black library buckram slip-case, blind embossed to the front, was limited to 21 hand bound exemplars bound in dark green goat leather with gold foil blocking to the spine and a unique verdant image on the front. Each copy of the fine edition came with a cream envelope containing a dried leaf from a Flying Rowan tree, ritualistically harvested by the author in her garden.

Published by Troy Books

Is this book available on audio book?

You can check the Troy Books website for such information, they have a section listing which titles are available as audio books.