Drawing Spirit is a study of the art, production and social functions of Late Antique ritual artefacts and their visual role in ritual practice, with case studies on exemplars drawn from the Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri and the Heidelberg Magical Archive. Its stated aim is to establish a new approach that provides a holistic understanding of the multi-sensory aspects of ritual, and to explore the transmission of knowledge traditions across faiths. Editors Jay Johnston and Iain Gardner contribute most of the entries here, with credits for two essays each, but Julia Kindt and Korshi Dosoo also add to the mix. This line-up makes for something of a Sydney University showcase, with all contributors, save for Dosoo, being professors in either its religion or classics departments.

Drawing Spirit is a study of the art, production and social functions of Late Antique ritual artefacts and their visual role in ritual practice, with case studies on exemplars drawn from the Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri and the Heidelberg Magical Archive. Its stated aim is to establish a new approach that provides a holistic understanding of the multi-sensory aspects of ritual, and to explore the transmission of knowledge traditions across faiths. Editors Jay Johnston and Iain Gardner contribute most of the entries here, with credits for two essays each, but Julia Kindt and Korshi Dosoo also add to the mix. This line-up makes for something of a Sydney University showcase, with all contributors, save for Dosoo, being professors in either its religion or classics departments.

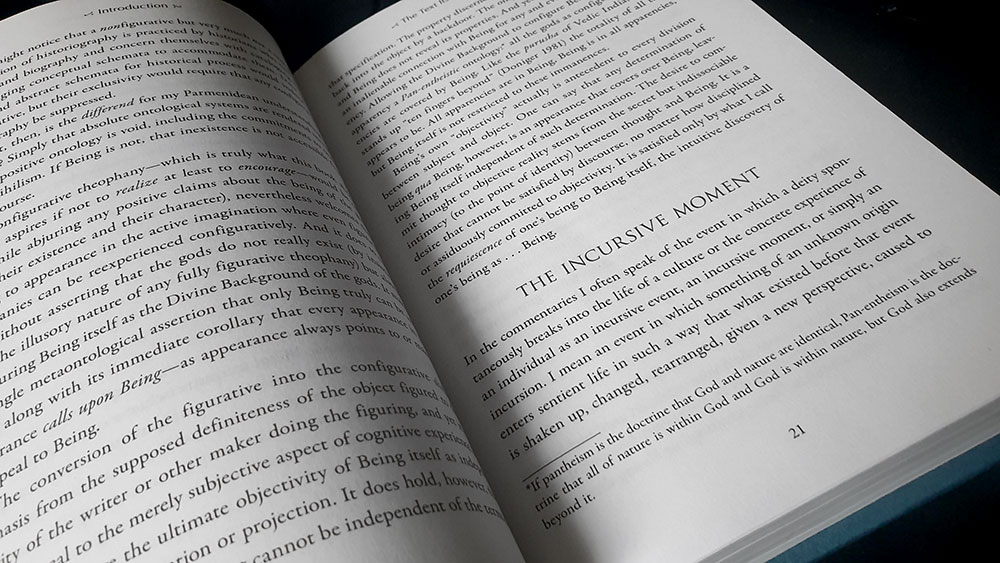

Co-editor Jay Johnston opens the proceedings with the supremely prolegomenal Magical Images: An Esoteric Aesthetics of Engagement, setting out in a dry manner ideas of images and their interpretation. In what may seem counterintuitive to a work that is focused on the analysis of images, Johnston advocates for an Esoteric Aesthetics, a new approach to interpreting texts and images that challenges empirical and essentialist representationalism. Instead of having a prescribed set of definitions by which text and images can be interpreted, Esoteric Aesthetics opens itself to a multiplicity of interpretations. Inherent in this approach is the idea that ritual objects were read on multiple levels by practitioners, rather than simply looked at.

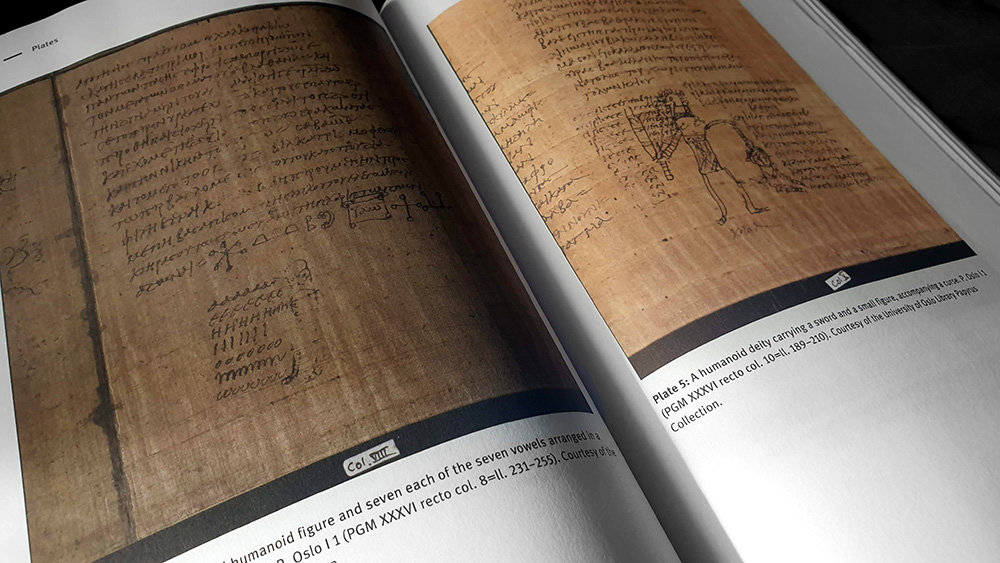

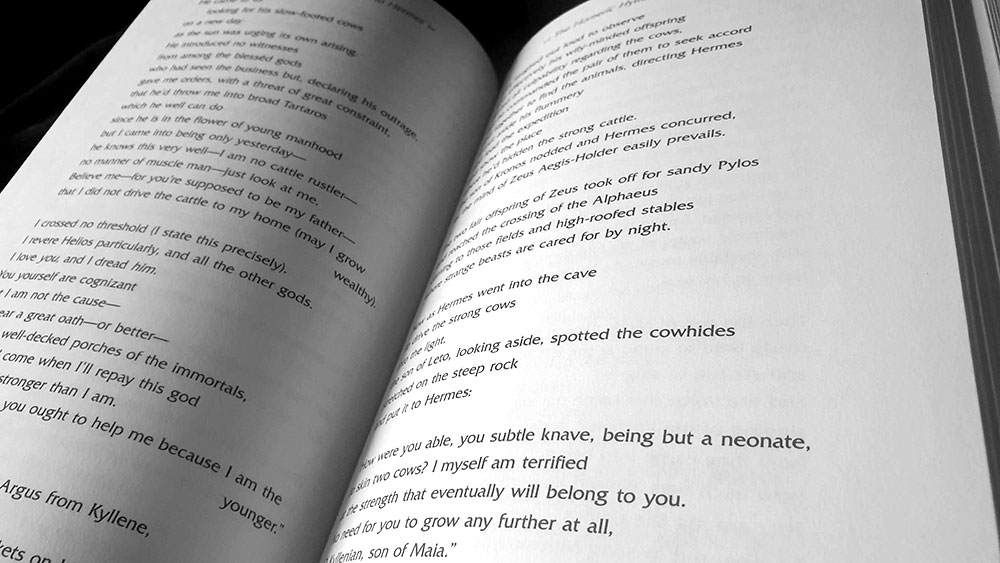

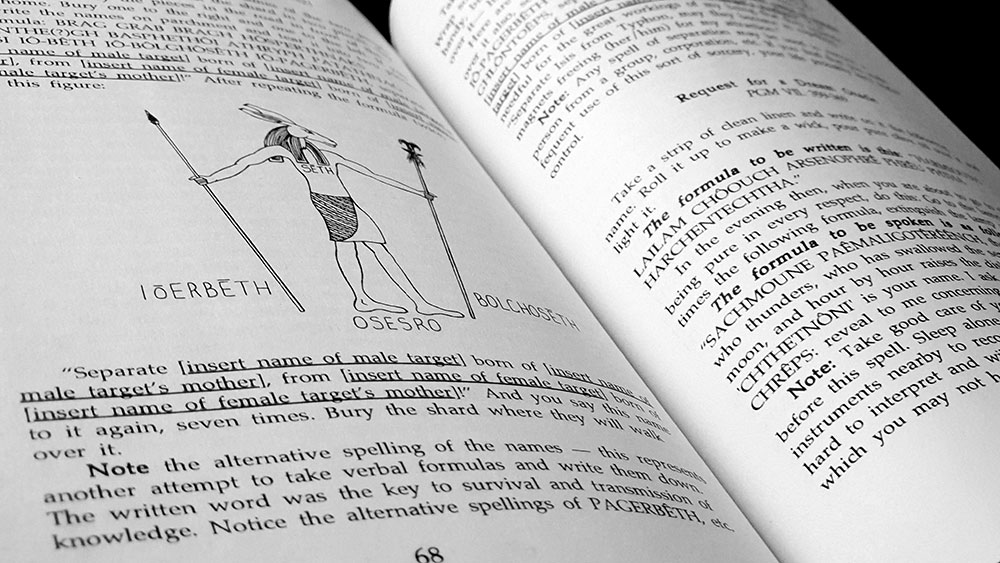

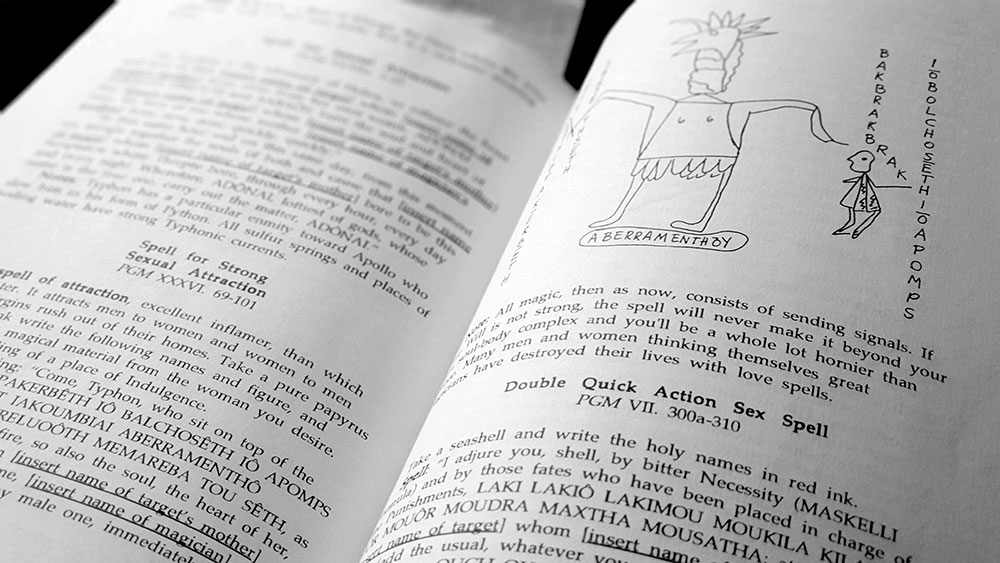

In Evoking the Supernatural: Text and Image in Graeco-Egyptian Magical Papyri, Julia Kindt considers the presentation of images and drawings in some of the papyri from what is known as the Theban Magical Library, a body of material from the third to fourth century CE, acquired in the early nineteenth century from art dealers in Luxor by the Swedish-Norwegian consul Giovanni Anastasi. Kindt proffers two case studies, both involving evocatively drawn figures whose exact-as-possible replication by a magical practitioner is essential for ritual efficacy. The first of these from PGM II, provides procedures for invoking Apollo in order to acquire prophetic revelations and features a depiction of a scarab beetle and of the headless daemon Akephalos. This Akephalos is the same Headless One invoked in what is known as the Headless Ritual from another papyrus, PGM V. 96-172 and which, thanks to a mistranslation, has in modern times be rebranded by the likes of the Golden Dawn and Thelema as the Bornless Ritual. Akephalos is as enigmatic as ever, carrying some sort of device in his right hand, his missing head replaced with a row of five symbols resembling the letter ‘q’ or stylised bird heads, while his torso is covered with tattoo-like voces magicae.

Given that Setians such as Don Webb have identified Akephalos with the Egyptian god Set (see the previously reviewed Seven Faces of Darkness), it is interesting that Kindt’s second case study is a charm of restraint in which Set/Typhon is summoned. His chimerical image is to be inscribed on a lead tablet along with various names of power and placed near the person to be restrained, giving evidence, as the Akephalos charm does also, to Kindt’s premise that such illustrations are by no means secondary in this form of magic and perform a fundamental function.

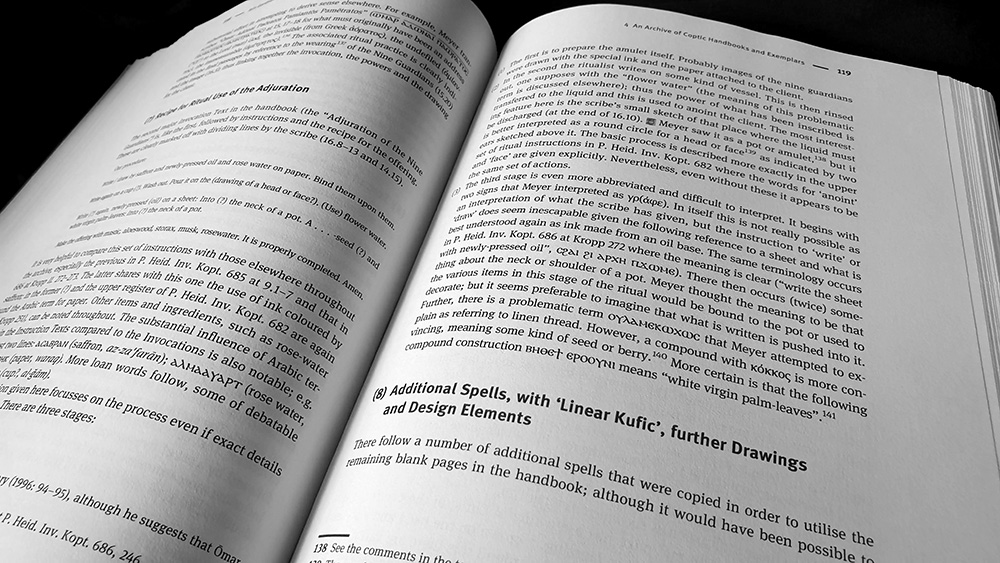

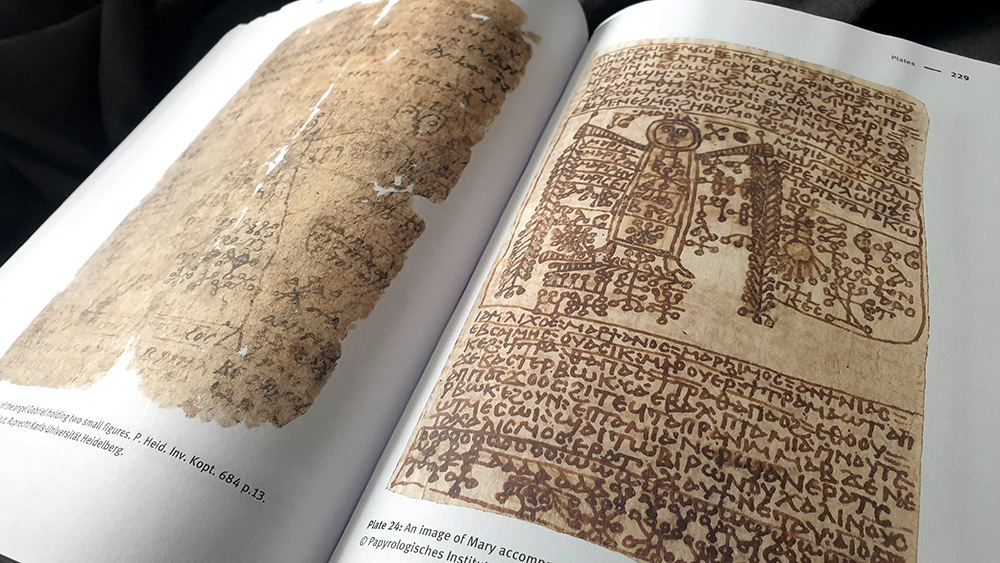

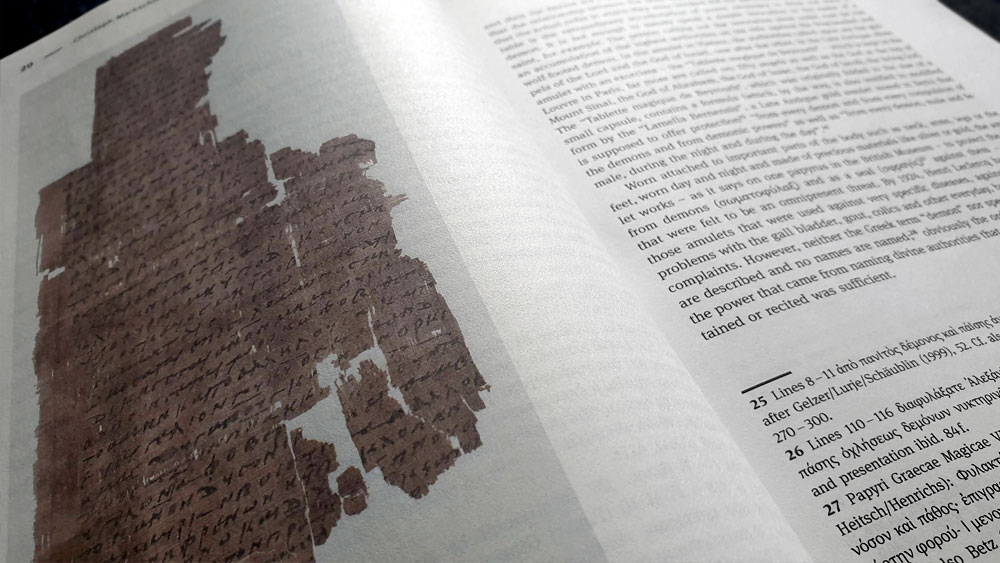

Co-editor Iain Gardner makes the largest contribution to this volume with the next two chapters, both of which act as surveys of the formatting of collections of magical texts conserved at the Institutfür Papyrologieat at Heidelberg University. One is a set of artefacts acquired through two purchases in 1930 and 1933 and now designated as P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 678–686, whilst the other, P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 680–683 and 685–686, is a tenth century archive of Coptic handbooks and exemplars for the making of amulets and gaining ritual power. The entries in both essays follow a similar pattern, opening with catalogue title of the respective manuscript, a perfunctory material description and a bibliography of previous related literature, before giving a supremely thorough analysis of the text in terms of it literary content and its decorations and illustrations. The first and shortest of these two chapters deals only with the aforementioned P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 678–686, as an exemplar, with the rest of the chapter acting as an extensive and highly technical introduction to the Heidelberg Magical Archive, its origins, content and purpose.

With his second essay alone running to 61 pages, Gardner’s sedulity is admirable, uncovering every detail and marking every observation for each entry, but it does make it hard work to get through. Gardner defines his exhaustive analyses of the six exemplars as consisting of notes and discussions undertaken at different times, and sequenced here without any greater editorial intent, and this is very much how it feels, making them a little disconnected and lacking in focus. This isn’t helped by the scission between this lexical and visual material and its broader origin within each manuscript. Although Gardner does include smaller photographic details of the various scriptural elements he is describing, there are no immediately accessible complete views of the entire pages to provide context. These are included as full-page plates in a comprehensive and valuable appendix at the end of the book, but it is exhausting having to flick back and forth betwixt the two. With that said, as a resource this is a nonpareil analytical reference worthy of coming back to when seeking to understand the content and in particular the minutiae of some of these Coptic manuscripts.

Korshi Dosoo continues the thread of Australian academia amongst this volume’s authors, having completed his doctorate at Macquarie University, Australia. He is now one of the two principal investigators for CoMaF (the Corpus of Coptic Magical Formularies project at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg), a project whose members, fun fact, also includes another Macquarie alum, David Tibet of Current 93. Dosoo brings his Coptic expertise to his contribution, Two Body Problems: Binding Effigies in Christian Egypt and Elsewhere, providing a broad, summary of the use of effigies, both two and three dimensional, in the magical practices of Europe, North Africa and Western Asia, before getting into the weeds with three brief case studies. The first of these is Miracles of Mercurius, a story from the Coptic magical texts in which a boy offers to pay a magician for a love spell. Dosoo’s other case studies are direct magical instructions found in the manuscripts P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 679 and P. Würzburg 42.

Co-editor Johnston wraps everything up with Image Play: On Angels and Insects, in which he applies his framework of Esoteric Aesthetics to a single image, this volume’s cover star, drawn from The Exaltation of Michael the Archangel P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 686 fol. 4r. The same image was also considered by Iain Gardner in his exhaustive chapter, but Johnston defines his own analysis as an experiment in provocation, rather than a presentation, using it as an example of a wildly speculative but internally coherent interpretation. Rather than seeing the image as being of St. Michael as simply a humanoid angel, Johnston asks, what if the depiction is of a winged insect, with what is usually taken to be Michael’s haloed head being a moth or butterfly emerging from its chrysalis or cocoon. Johnston enables this exercise in Esoteric Aesthetics by calling on textual examples of butterflies and other insects as spiritual figures (such as the belief in moths as ‘soul-birds’), as well as explaining the obvious associations with resurrection that one can make for lepidopteran metamorphosis. While Johnston is thorough in this analysis, there’s never a sense that it’s an interpretative hill he would die on, and in the end, it is what it is, a diverting and enjoyable exercise in theoretical what ifs.

Drawing Spirit incorporates twelve monotone illustrations and 69 coloured ones, with 32 of the latter being full page plates (on regular, non-gloss stock) placed as an invaluable appendix at the back. The variety of contributions makes this an intriguing read, but with Gardner’s extensive analysis taking up so much space, its true value seems to be as a reference, rather than a digestible collection of essays.

Published by de Gruyter