Part of the expansive Magic in History series from Pennsylvania State University Press, Conjuring Spirits is an academic work that calls to mind Scarlet Imprint’s more experientially-orientated compendiums Howlings and Diabolical, in that it brings together essays on various magical texts and manuscripts, albeit from an entirely scholarly perspective. The contributions in Conjuring Spirits are divided into two sections, Context, Genres, Images and Angelic Knowledge, with the latter focussing on just two texts, the Sworn Book of Honorius, and John the Monk’s Book of Visions. Presenting both general surveys and more specific analyses are Michael Camille on two examples of the Ars Notoria, Robert Mathiesen on the Sworn Book of Honorius (also discussed alongside the Liber Visionum by Richard Kieckhefer in a separate entry), John B. Friedman on the Secretum Philosophorum, Elizabeth Wade on Lullian divination, while Nicholas Watson and editor Claire Fanger each separately discuss John the Monk’s Book of Visions of the Blessed and Undefiled Virgin Mary, Mother of God. Finally, this book also includes Juris Lidaka’s edition of the Osbern Bokenham-attributed Liber de Angelis, and an overview by Frank Klaassen of late medieval English ritual manuscripts.

Part of the expansive Magic in History series from Pennsylvania State University Press, Conjuring Spirits is an academic work that calls to mind Scarlet Imprint’s more experientially-orientated compendiums Howlings and Diabolical, in that it brings together essays on various magical texts and manuscripts, albeit from an entirely scholarly perspective. The contributions in Conjuring Spirits are divided into two sections, Context, Genres, Images and Angelic Knowledge, with the latter focussing on just two texts, the Sworn Book of Honorius, and John the Monk’s Book of Visions. Presenting both general surveys and more specific analyses are Michael Camille on two examples of the Ars Notoria, Robert Mathiesen on the Sworn Book of Honorius (also discussed alongside the Liber Visionum by Richard Kieckhefer in a separate entry), John B. Friedman on the Secretum Philosophorum, Elizabeth Wade on Lullian divination, while Nicholas Watson and editor Claire Fanger each separately discuss John the Monk’s Book of Visions of the Blessed and Undefiled Virgin Mary, Mother of God. Finally, this book also includes Juris Lidaka’s edition of the Osbern Bokenham-attributed Liber de Angelis, and an overview by Frank Klaassen of late medieval English ritual manuscripts.

It is Klaassen’s survey of late medieval English manuscripts with which the proceedings open, being an appropriately broad grounding in the genre, even if not all of the works discussed in this book come under that category. Lidaka’s translation of Liber de Angelis follows, being introduced with a brief essay in which he gives a history of this manuscript, establishing early on that the attribution to the Augustinian friar and poet Osbern Bokenham is incorrect, and that the Bokenhan to whom authorship is credited may actually have been one William Bokenham. Liber de Angelis is not a single liber and instead consists of extracts from at least three texts, as evidenced by the demarcation into sections on making rings for each of the planets (ordered from Sun to Saturn), followed by Liber de ymaginibus planetarum, in which instructions are given for creating images of the planets but with the spheres in a different order to the rings, and ending with Secreta astronomie de sigillis planetarum & eorum figuris in which the planets are ordered differently once again in a guide to creating planetary magic square. Given some of the errors in the original text of Liber de Angelis, such as the numbers in some of the magic squares not calculating correctly and the names of planetary angels differing from other sources, Lidaka argues that the texts were transcribed by an enthusiastic amateur, someone with a general interest in magic though less concerned with slavishly getting everything right.

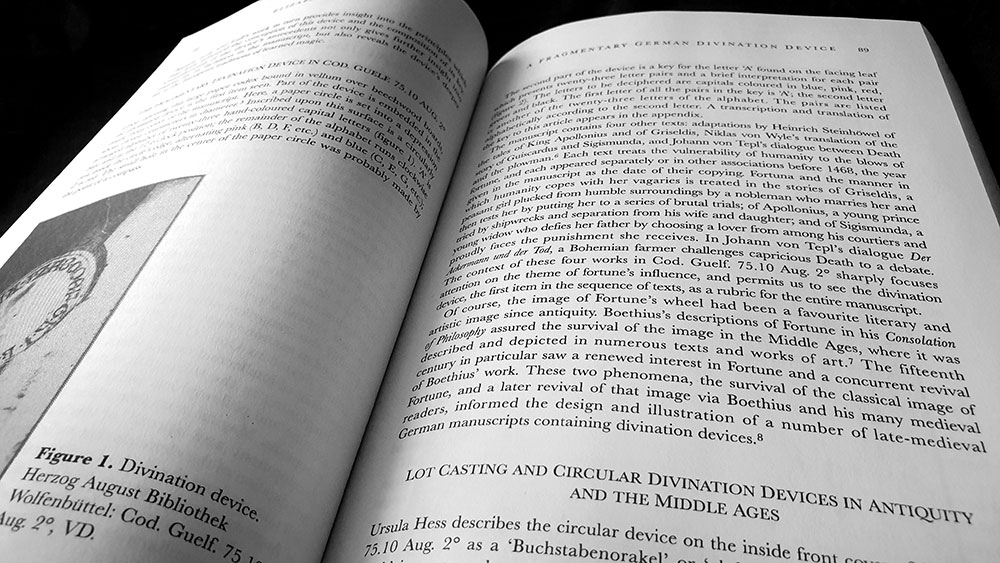

John B. Friedman’s consideration of the Secretum Philosophorum is a rather dry and technical history of the text, feeling a little out of place given its focus not on ritual magic but on tricks and experiments demonstrating various aspects of the seven liberal arts. Friedman does argue that the text is an example of ‘safe magic,’ using the appearance of sorcery, with its diagrams and occasional acknowledgement of hermetic authority, to give a theoretical matrix to technology and convey ideas of power and learning. Elizabeth Wade also makes a diversion away from grimoires to discuss a fifteenth century German divination device found in a large paper codex catalogued as Cod. Guelf. 75. 10 Aug. 2°. Said fragmentary device is not necessarily the entire focus here and Wade uses it as a starting point for a broader primer on Lullian and pseudo-Lullian forms of mechanical divination, as well as their medieval analogues.

Robert Mathiesen’s essay on the Sworn Book of Honorius focuses not on its use as a Solomonic grimoire for ceremonial magic, and instead on one of only two magical operations to survive in its six known, and presumably partial, manuscripts. While the second (and according to Mathiesen, less interesting), of the operations is for the summoning to appearance of an angel, spirit or demon, the first is a byzantine ritual for attaining the beatific vision, effectively creating a shortcut to the eschatological goal of Christianity. Mathiesen begins with a preamble giving the history of the sworn book, and then a summary of the rite itself, which still runs to several pages despite not being presented in its entirety. There’s little analysis of individual components of the rite and Mathiesen concludes with a discussion on the efficacy of such complicated ritual formulae (he seems pretty assured that it would get some kind of result), and thereby suggests that the rite’s potential to undercut the religious foundation of the medieval world would account for William of Auvergne’s description of the Sworn Book of Honorius as the very worst book of magic in circulation.

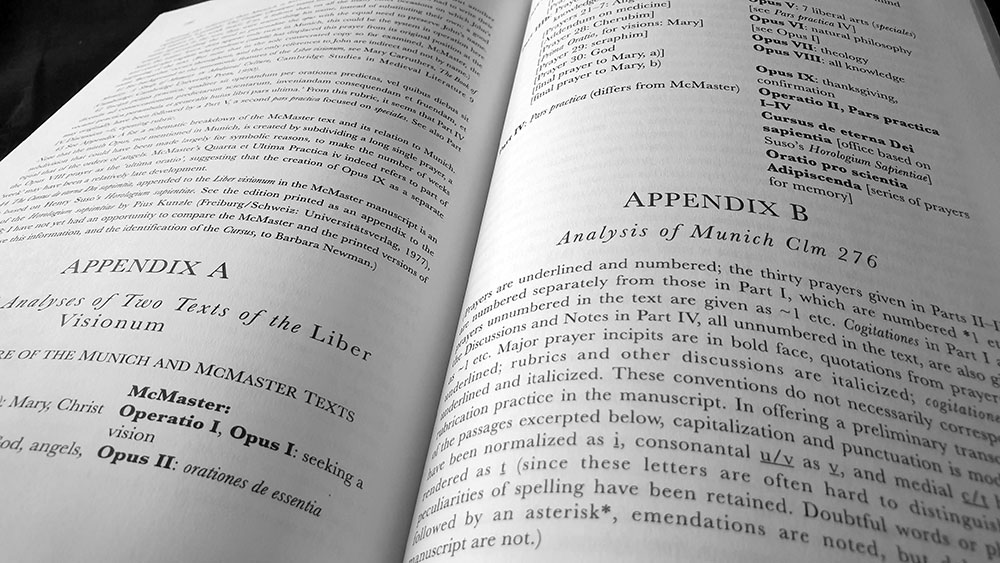

Two essays from Nicholas Watson and editor Claire Fanger are unique in that a hitherto unknown manuscript version of their subject, John the Monk’s Liber Visionum, had, at the time of writing in 1998, been recently discovered at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada; while several other full and partial manuscripts have since been found in various European archives. It is worth mentioning that Flanger has subsequently shown that, as per John the Monk himself, the work should be more accurately called Liber florum celestis doctrine, with only its first, autobiographical section being called the Liber visionum, but for the sake of consistency and the convention established by this volume, we’ll keep the archaic naming in this review. With the McMaster version of the Liber visionum being uncovered by Watson and then translated and thoroughly documented by Fanger, there’s a personal feel to the considerations here. Watson discusses the relationship between the McMaster manuscript and another one discovered in Munich, as well as contextualising the work in terms of the broader devotional and mystical tradition upon which it draws. Watson is exhaustive in his analysis, resulting in the longest entry in Conjuring Spirits, running to 52 pages, aided and abetted by extensive endnotes and several appendices: structural analyses of the McMaster and Munich manuscript, as well as individual summaries of both versions. After that, Fanger shows that there’s still more to be said about John the Monk’s text with her own essay in which she considers its relations to the Ars Notoria on which it is modelled. For her own appendix, Fanger provides a synopsis of a prologue from a version of the Liber visionum from the University of Graz library.

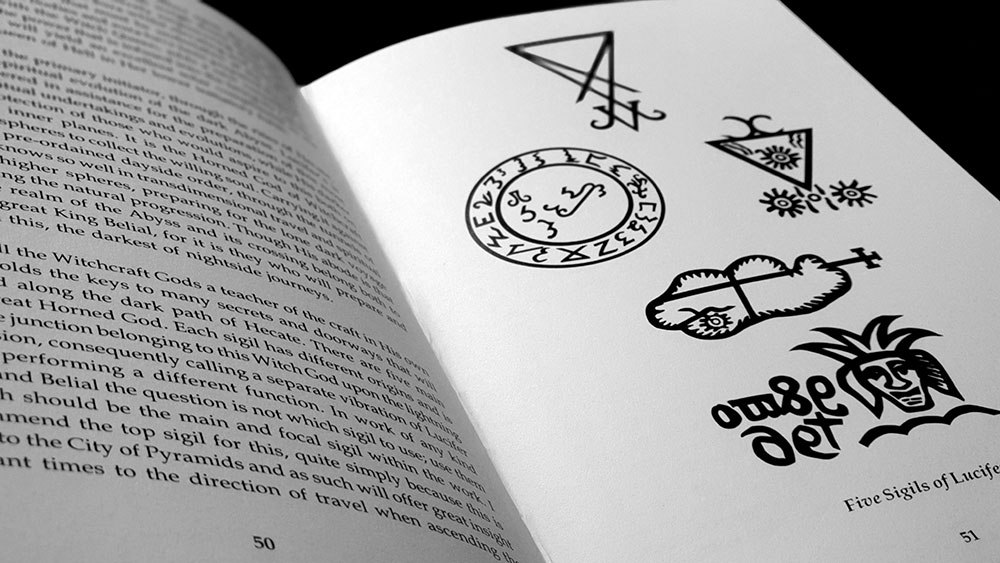

John the Monk makes another appearance in Michael Camille’s consideration of examples of ars notoria imagery from various manuscripts, which opens with a vituperative quote from the Grandes Chroniques de France in which the monk of Morigny is pilloried for his wish, through his curiosity and pride, to renew the heretical and sorcerous notary art under another name. John the Monk’s own Marian 0figures are not the focus here, though, and Camille considers the notae from the thirteenth century Turin manuscript (MS E. V.13) and the fourteenth century Paris BN lat. 9336. The images are recipients of detailed discussion, with Camille bringing to them an art historian’s focus by tracing provenance and making comparisons with other examples of medieval pictorial and diagrammatic content. Photographic examples of the notae, as well as their analogues, are included, many at full size, though the quality of reproduction is not the greatest, with a blurry murk and a lack of contrast.

Conjuring Spirits concludes with Richard Kieckhefer’s The Devil’s Contemplatives, in which he considers the two titles already exhaustively discussed within this volume: the Liber Iuratus Honorii (aka the Sworn Book of Honorius) and once again, John the Monk’s Liber Visionum. Kieckhefer’s point of difference, though, is analysing how both texts are evidence of the Christian appropriation of various elements from Jewish occultism. He emphasises the way in which both the Liber Iuratus and the Liber Visionum focus less on the typical goetic summoning of demons and rather on a form of devotional mysticism; an approach, he argues, that has little precedent in Western occultism and is instead drawn from Kabbalah, particularly the vision-rich Merkabah tradition. The previously-discussed ritual for attaining the beatific vision from the Liber Iuratus is an obvious example of this, as is John the Monks devotional reverence towards the Virgin Mary. While the attitude of these Western and Kabbalistic systems is circumstantially similar, Kieckhefer has no smoking gun, with the closest being a version of the Liber Iuratus that includes the Shem HaMephorash, Kabbalah’s secret name of God, in the design of a seal used for acquiring a dream vision.

Despite this book’s title, there’s relatively little that concerns itself with the conjuring of spirits here, with far greater focus on the devotional and reflective elements seen in works such as the Sworn Book of Honorius and Liber Visionum, and even in considerations of the mental self-improvement and memory aides showcased in the Ars Nortoria and the Secretum Philosophorum. With John the Monk looming over many of the contributions here, Conjuring Spirits is a valuable resource on the Liber Visionum, being the largest consideration of the text at the time of publication; though now rivalled by Fanger’s 2015 book, Rewriting Magic: An Exegesis of the Visionary Autobiography of a Fourteenth-Century French Monk, also published by Pennsylvania State University Press.

Conjuring Spirits, like other titles in the Magic in History series, appears to be available in two editions. One of them features the classic, sombre and refined Penn State Press Magic in History cover template, whilst the other, reviewed here, has a cover design that is slightly more in keeping with an Inner Traditions or Weiser mass market title, all green gradient, low opacity goetic sigil and large drop-shadowed type. In at least this copy, apparently printed-on-demand by Ingram, there is a printing error, where the cover has skewed a couple of degrees off base, meaning that the spine print is noticeably misaligned, with a crooked sliver of the cover’s green gradient creeping into the spine, and a corresponding slice of black spine sneaking round onto the back matter. This same on-demand printing may account for the poor quality reproduction of images.

Published by the Pennsylvania State University Press