The first issue of the Helvete journal was previously reviewed here on Scriptus Recensera and was described as an interesting if flawed look at black metal through an academic lens. This second issue continues that approach and features contributions from Elodie Lesourd, Reuben Dendinger, Brenda S. Gardenour Walter, Louis Hartnoll, Erik van Ooijen, Bert Stabler, and editors Niall Scott and Steve Shakespeare. In their introduction, Scott and Shakespeare identify the inverted cross as emblematic of the themes of this issue, providing an overview of the contributions within and arguing that the power of inversion is not simply one of parodic reversal, instead opening new ways of thought through the collapsing of light into darkness, pointing beyond a narrative of salvation (in which one master is replaced with another, darker hued), and instead “towards an identification with the earth in its reality, in its corruption.”

The first issue of the Helvete journal was previously reviewed here on Scriptus Recensera and was described as an interesting if flawed look at black metal through an academic lens. This second issue continues that approach and features contributions from Elodie Lesourd, Reuben Dendinger, Brenda S. Gardenour Walter, Louis Hartnoll, Erik van Ooijen, Bert Stabler, and editors Niall Scott and Steve Shakespeare. In their introduction, Scott and Shakespeare identify the inverted cross as emblematic of the themes of this issue, providing an overview of the contributions within and arguing that the power of inversion is not simply one of parodic reversal, instead opening new ways of thought through the collapsing of light into darkness, pointing beyond a narrative of salvation (in which one master is replaced with another, darker hued), and instead “towards an identification with the earth in its reality, in its corruption.”

Obviously, one of the appeals of black metal, to fans and academics alike, is aesthetics, and indeed the discussions here focus more often on things visual than things aural. The appeal of the imagery of black metal gives some of these contributors license to wallow in its dark glamour, employing its eldritch visual lexicon for equally florid prose. Brenda S. Gardenour Walter, for example, opens her piece Through the Looking Glass Darkly drawing a scene set in “sempiternal night, ice-laden autumn winds twist through gnarled and blackened woodlands as shadows grow long beneath a freezing moon.” Here, inverted crosses, inverted pentagrams and the severed heads of sheep “flicker in the firelight cast from the conflagration of Christian stave churches in the distance.” Walter presents black metal as a multi-layered darkened mirror that contains multiple inversions upon inversions which thereby conceals several potential identities for its devotees. She identifies within the first layer of the mirror the ability for black metal to act as a path to liberation and self-empowerment, with the embracing of what mainstream society and religion abhors creating an assured identity in opposition; albeit one whose principle of reactionary abjection binds it to its object of hatred through a co-dependent jouissance.

Taking black metal’s elitism and contrariness to its ultimate extreme, Walter argues that there is another identity that can be found within the darkened mirror of black metal, one that moves beyond the validation by opposition seen in the Satanism-Christianity antinomy. Rather than being a subscriber to some of black metal’s more pervasive orthodox tendency (the true bands, the right clothes… no sneakers or tracksuits, please), this figure in the mirror, acknowledged here as illusive and distant, is more a Luciferian and intellectual ideal, refusing to submit to anyone’s will, be it God, Satan or the black metal group mind. Here, Walter again returns to her kvlt, grim but picturesque language, describing this Byronic figure as a “single blackened self, standing alone in a barren waste, much like a gnarled and blackened tree against a northern winter sky.” Embracing the language of anti-cosmic Satanism, this nihilistic and blackened self experiences a moment of dark illumination as it sees its inverted reflection reverberating into a formless void, a void in which they achieve true liberation through destruction. “At the still point, in a moment of ecstatic union with the darkness, the self is annihilated in blackness and absorbed into the Oneness of Nothing, unfettered at last.”

Equally heavy on the lovely language is Reuben Dendinger who discusses black metal as folk magic in The Way of the Sword, with said sword being, in his eyes, totemic of metal itself and synonymous with the inverted cross. Dendinger presents the history of metal music as a modern yet ancient myth with its practitioners euhemerised into wielders and workers of steel, building motorbikes in the 1970s, and then going underground in the 1980s where they forged great blades and freed the witches, pagan heroes and the exiled pagan gods that would come to embody the genre from their imprisonment in Hell. Heady stuff; though unfortunately it doesn’t give a mythic explanation for hair metal, or Stryper for that matter.

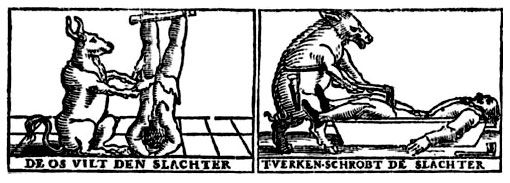

Things stray away from black metal when Erik van Ooijen turns to the death metal/deathgrind of Cattle Decapitation in Giving Life Harmoniously. This continues the issue’s theme of inversion but this is not a case of religious antithesis, though it is a moral one, with Ooijen considering the way in which Cattle Decapitation inverts the traditional hierarchy of human and animal. With its vegetarian stance that turns factory farming and industrialised slaughter against its humans perpetuators, the band’s imagery, Ooijen argues, challenges and inverts the familiar violent themes, misogynies and hierarchies found within the grindcore and death metal genres as a whole, thereby enacting a queering of the carnophallogocentric (to use a term from Derrida) form. This is something hiding in plain sight in the band’s name, able to be read as the conventional decapitation of cattle, or the inverted and righteous revenge of decapitation by cattle. This conceit, and in particular its representation in the band’s cover art, has a precedent in the reversal of power relationships seen in the 14-18th century topos of mundus inversus, the world turned upside down, typified here in a series of Dutch woodcuts that includes scenes of an ox flaying a suspended butcher, or a goose and rabbit roasting a cook on a spit.

Another musical tangent is seen in Bert Stabler’s A Sterile Hole and a Mask Of Feces which takes as its launching pad An Epiphanic Vomiting of Blood, the title of the third full-length studio album by Gnaw Their Tongues, an act perhaps more associated with metal-accented dark ambient and noise. There’s not a lot of Gnaw Their Tongues here, though, and after an initial mention, Stabler swiftly moves away from them, grounding his discussion in the works of Hegel as interpreted by Slavoj Žižek, presenting a textually and theoretically dense consideration of themes of ecstatic disintegration and the embracing of the abjected in sublation/aufheben. This narrative wanders somewhat aimlessly and erratically, with Stabler swinging various theoretical models around recklessly and dropping examples and diversions out of nowhere, with those drawn from black metal often feeling tacked on to an existing whole.

Like the first volume of Helvete, there is a visual component here, with Elodie Lesourd and Amelia Ishmael curating Eccentricities and Disorientations: Experiencing Geometricies in Black Metal, featuring artwork by Dimitris Foutris, Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert, Andrew McLeod, Sandrine Pelletier, and Stephen Wilson. As one would expect, given the title, this collection explores themes of space and geometry, with the vaults, beams and buttresses of churches being a constant reference. Bouschet and Hilbert reprise their blackened aesthetic from Helvete 1 with a regrettably brief contribution, but the most striking pieces here are stark, detailed shots of Sandrine Pelletier’s sculpture Aeg Yesoodth Ryobi Ele_emDrill!, a linear three-dimensional pentagram whose blackened beams recall the remains of a scorched cathedral as much as they do some impossible, Lovecraftian non-Euclidean geometry. Lesourd and Ishmael accompany this selection of work with text that occasionally breaks from standard formatting into more idiosyncratic, not-entirely successful layouts indicative of the theme, pushing the text into geometric shapes or inconsistent column widths.

This second volume of Helvete makes for some interesting, diverting reading, with, for what it’s worth, the non-black metal contribution from Ooijen being the most engaging and well written; albeit long. He ably combines theoretical models with an integrated consideration of Cattle Decapitation, weaving in related factoids or anecdotes where relevant. As with the first issue of Helvete, there are some issues here, with questions inevitably arising over whether black metal is written about simply from the perspective of a dilettantish embracing of something exotic and transgressive. Similarly, Norwegian black metal continues to loom large, almost to the point of eclipsing all others; something that literally happens in Contempt, Atavism, Eschatology, where Louis Hartnoll mistakenly but consistently refers to the nineties Norwegian scene as the first wave of black metal, rather than the second, giving it primacy over all that went before and thereby casting Øystein Aarseth as some sort of black metal prime progenitor.

Published by Punctum Books.