Translated and edited by Edred Thorsson and published in 1993 by his Rûna Raven imprint, Siegfried Kummer’s Rune=Magic was originally released as Runen=Magie exactly 60 years prior. Rune=Magic is, in some ways, a condensed form of Kummer’s considerably larger Heilige Runenmacht from 1932, and was the fourth volume of Germanische Schriftenfolge; a series which also included Der Alfred Richter’s Heilgruß: seine Art und Bedeutung and Jorg Lanz von Liebenfels’ Ariosophisches Wappenbuch.

Translated and edited by Edred Thorsson and published in 1993 by his Rûna Raven imprint, Siegfried Kummer’s Rune=Magic was originally released as Runen=Magie exactly 60 years prior. Rune=Magic is, in some ways, a condensed form of Kummer’s considerably larger Heilige Runenmacht from 1932, and was the fourth volume of Germanische Schriftenfolge; a series which also included Der Alfred Richter’s Heilgruß: seine Art und Bedeutung and Jorg Lanz von Liebenfels’ Ariosophisches Wappenbuch.

While Heilige Runenmacht is a comprehensive guide to the 18-rune Armanen Futharkh of Guido von List, providing both a thorough exegesis and a complex system of exercises, Rune=Magic offers just a few gems, as Kummer terms it, of wisdom and rune-magic. Kummer eschews the lengthy explanation of each rune in favour of brief, single paragraph synopsises, with which he opens the book. Similarly, the systems of rune yoga and runentänze, which are given a great deal of space in Heilige Runenmacht, are here replaced with runic hand exercises, notes of yodelling as a magical technique, and a series of standalone exercises.

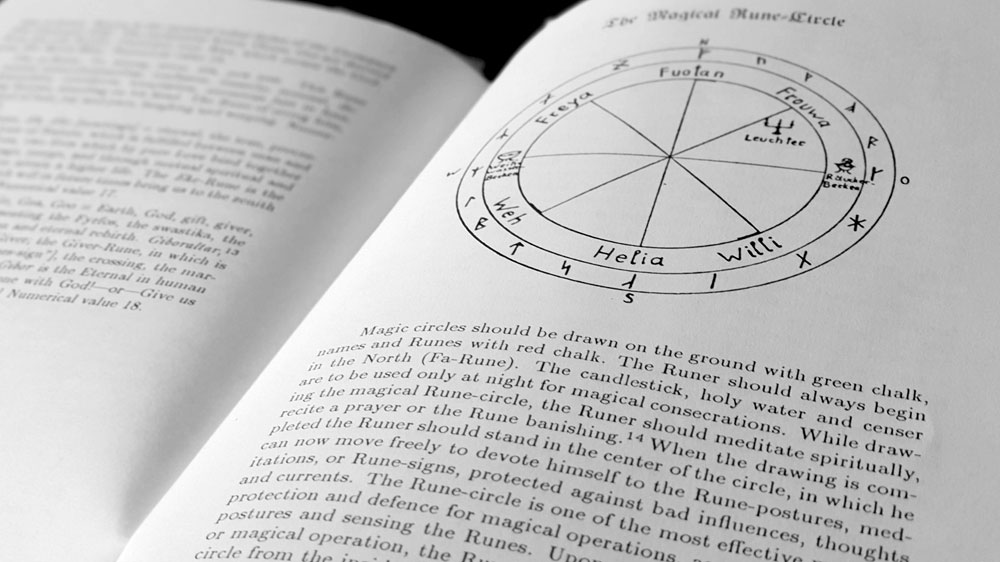

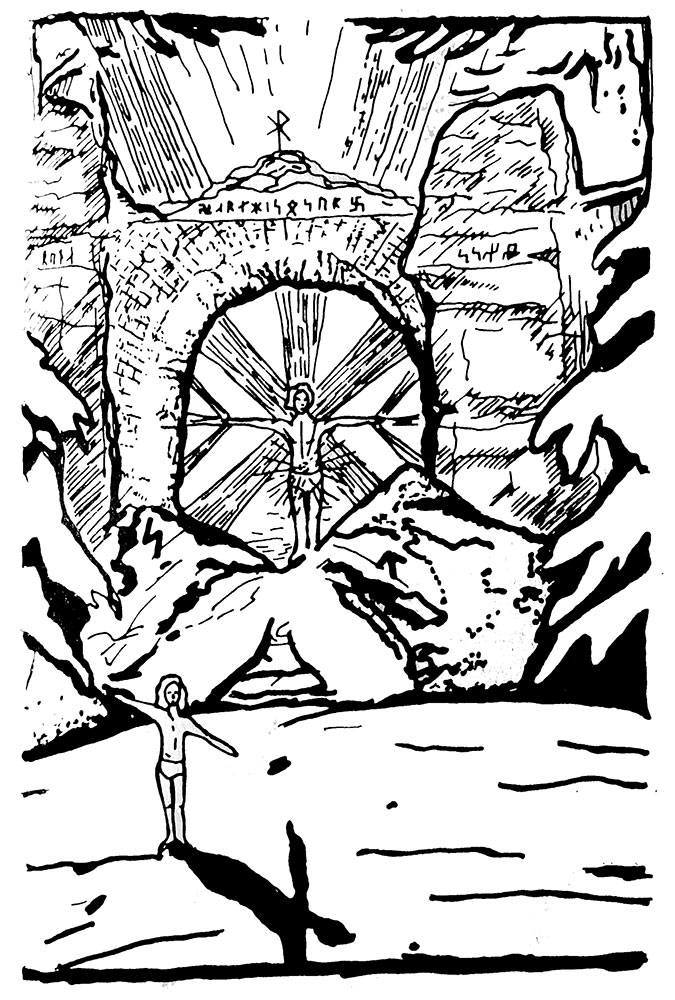

The first of these consists of three individual exercises that build upon each other, beginning with the casting of a somewhat atypical protective rune circle, within which the subsequent activities take place. With the circle cast, the practitioner performs an initial meditation based around the Man rune (which in the Armanen system and the Younger Futhark resembles the Elhaz rune, rather than the Elder Futhark’s m-like Mannaz). The final ritual in this sequence transforms the practitioner’s Man rune stance into a visualised light body, an energy form known as the Grail-Chalice that once completed, attracts higher, spiritual cosmic influences.

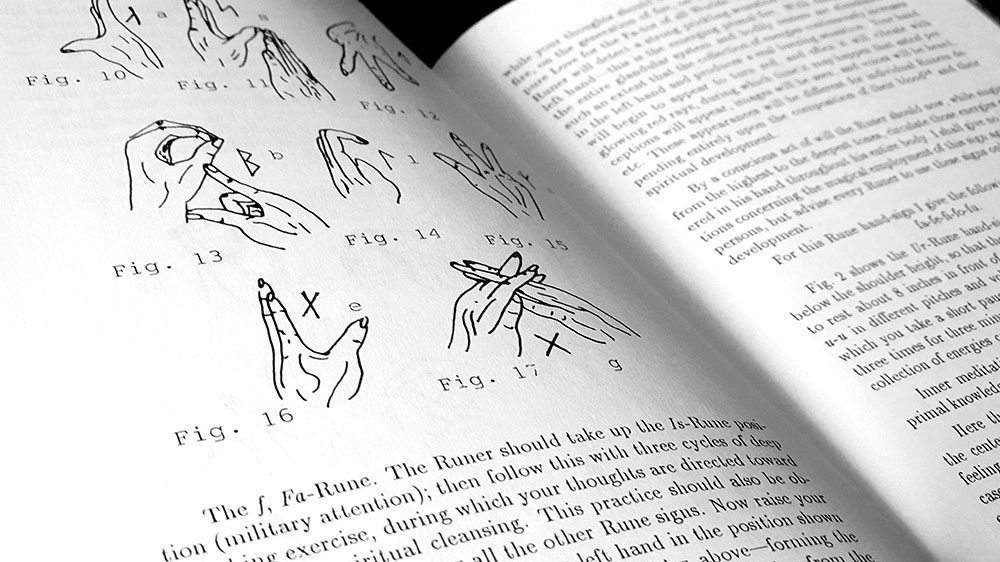

In place of the rune yoga and runentänze of Heilige Runenmacht, Kummer offers a literally scaled down system befitting the size of this volume. This takes the form of runic mudras (though Kummer does not use that term), a collection of hand gestures corresponding to each rune. Or rather, almost each rune, as Kummer leaves out a gesture for Yr, which as the Todesrune, may have been, as Thorsson suggests, considered too negative to be used. Karl Spiesberger, who subsequently elaborated on Kummer’s system, would later correct this omission and created a Yr mudra. Each of Kummer’s mudras works in the same way as the larger rune yoga forms do, being associated with particular vocalisations, meditations and astral colours, and producing aetheric and olfactory results.

The rest of Rune=Magic feels a little like a collection of miscellanea, with nothing particularly substantial and instead consisting of various short, largely unconnected pieces. There’s a list, with an accompanying diagram, of 24 important glands and higher centres of the body, and some magical rune formulas that either effect change or represent concepts such as wisdom and primal love. Then, as a natural conclusion, there are morning and evening consecrations and a poetic rune banishing.

As one would expect, Kummer’s cosmology and general approach has much in common with that of his runological contemporaries such as Peryt Shou, Friedrich Marby, and of course, List. There’s a certain dated style of etymology that ultimately seems dependent on the type of deism or monotheism that seeks to have its Judaeo-Christian cake and eat it too, but with Wotan-flavoured icing. Thus, the kind of linguistics that wouldn’t stand up in morphological court are used to see the name of God in the word ‘yodel,’ with the affirmative German ‘ja’ apparently evolving into the divine names Ya-weh, Yeho-va, Yo, Ya, Ye, and Yuh. Similarly, and in a slightly problematic moment, Kummer says that the Jews stole the word ‘jude,’ (“to which they have no right” apparently), which he says is a purely German word meaning ‘the good,’ similar to ‘Goth’ which is taken to mean ‘good’ or ‘godly.’

The other area which Kummer has in common with other runologists and Shou in particular is the use of then current technological nomenclature, embracing the paradigm of radio waves and antenna when discussing energy that the adherent could channel or generate. With this comes a heady sense of the cosmic, as mentioned in a previous review of Shou’s work, creating an endearing retro-futurist technological quality.

Rune=Magic is a slim volume, so much so that its 45 pages are saddle stitched and stapled. Inside, the body copy is set in a brittle-looking serif face that, by intent or not, is suggestive of the original publication’s period. This is offset with chapter headings in an obviously intentional condensed Fraktur-style blackletter, which is perfect for that archaic German feel. Images from Kummer’s original are scanned and reproduced well, with no pixilation or artefacts. Given its size, especially in comparison to Heilige Runenmacht, there’s inevitably a feeling that more could have been said in Rune=Magic. It’s not a primer as such, being too brief in some of the fundamentals even for that, but it does introduce some key and, at the time, unique techniques. Ultimately, though, the value of Rune=Magic is in its role as a historical document, and still one of the only, if not the only, works by Kummer translated into English.

Published by Rûna Raven Press