Published by Aeon Sophia Press, Music in Witchcraft and the Occult concerns itself with exactly what it says on the tin, but it approaches this theme from a practical and experiential perspective, with a variety of musician writing about the ways in which music and the occult interact within their work. But first, a little caveat, as this anthology includes an essay from this reviewer, discussing her creation of devotional music for Hela under the name Gydja. Suffice to say, we will be neither critiquing nor lauding that particular contribution, but even without that, there’s plenty more to explore.

Published by Aeon Sophia Press, Music in Witchcraft and the Occult concerns itself with exactly what it says on the tin, but it approaches this theme from a practical and experiential perspective, with a variety of musician writing about the ways in which music and the occult interact within their work. But first, a little caveat, as this anthology includes an essay from this reviewer, discussing her creation of devotional music for Hela under the name Gydja. Suffice to say, we will be neither critiquing nor lauding that particular contribution, but even without that, there’s plenty more to explore.

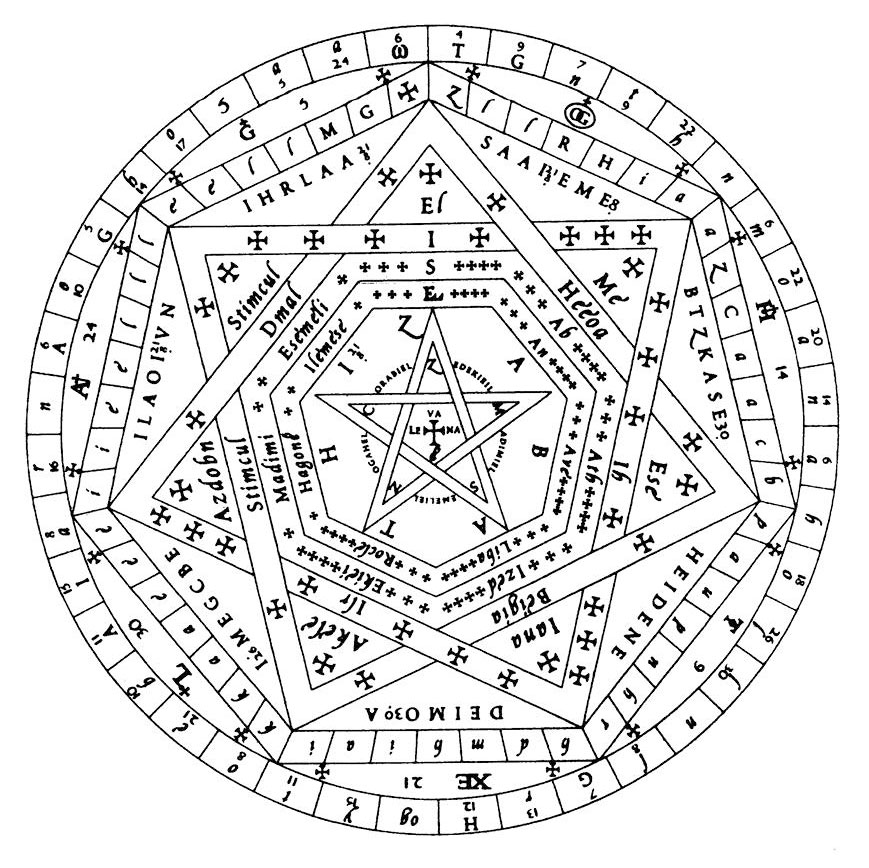

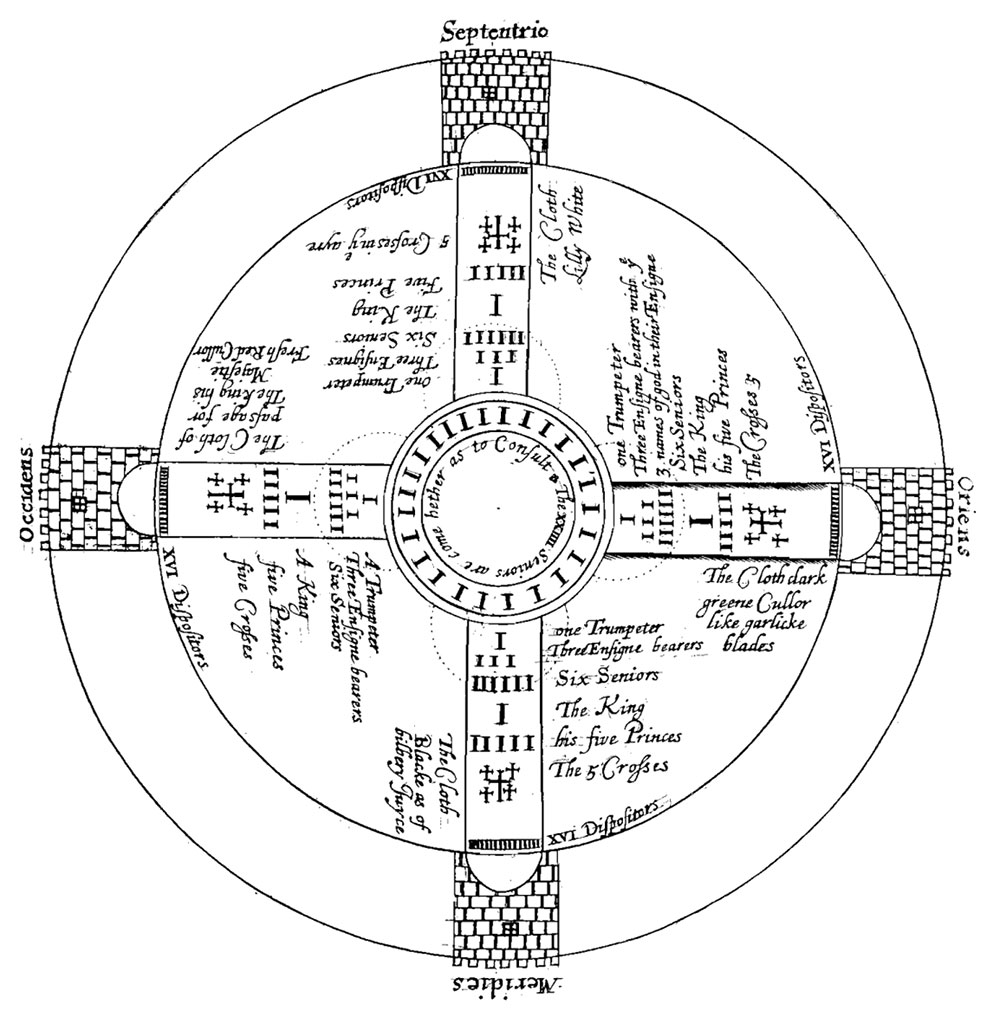

We usually leave matters of aesthetics to the conclusion of reviews, but the appearance of Music in Witchcraft and the Occult impacts on reading to such an extent that it informs what follows. There is unfortunately a haphazard quality to the layout, with no consistent style and with each entry apparently retaining its contributor’s source formatting. As a result, the inherited styling of subtitles, footnotes, footnote numbering, indents, captions, page beaks, line spacing and paragraph returns are all inconsistent; though mercifully, the same serif face is used throughout for the main body. This inevitably makes the book feel rushed, lacking in cohesion and genuinely hard to read in some places; such as the first entry in which the text is interrupted by strange, abrupt digits as the footnote numbering has been formatted at full scale instead of superscript. Most jarring of all are the main titles which have been left however the author minimally formatted them in their submission, resulting in barely any typographic hierarchy. Similarly, if an author didn’t include their name at the start of their original submission document, then it hasn’t been added here for publication, meaning that without recourse to the contents page you can dive into some entries with little context, hoping that the author’s name is mentioned latter on.

There are some interesting contributions in Music in Witchcraft and the Occult which makes it all the more frustrating that it doesn’t look better, especially when only a little tightening of the layout and the addition of hierarchy and consistency would have done wonders. After something of a broad introduction with a few personal specifics from Aaron Piccirillo of Synesect, the first entry comes from Kakophonix of self-described Black Ritual Chamber Musick project Hvile I Kaos. This is a comprehensive consideration of the music of Hvile I Kaos, with a guide to their performances as live rituals, an analysis of the theory behind some indicative pieces and albums, accompanied by notation of particular motifs, including a setting of the Agios O Baphomet sinister chant. It’s all rather interesting, though the lack of formatting makes it feel rather desultory, with huge half-page spaces left between sections and little in the way of typographic hierarchy.

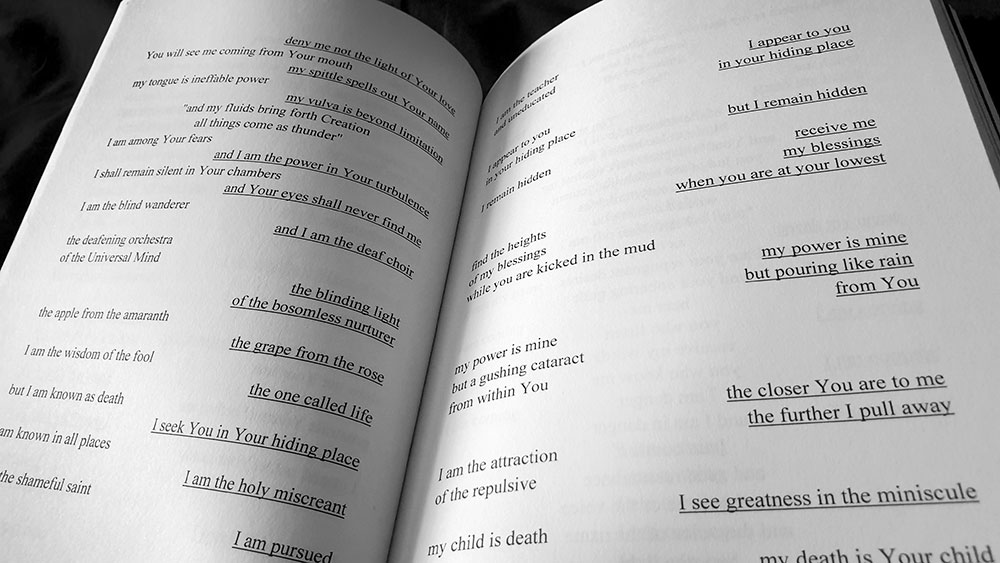

Zemaemidjehuty, author of The Book of Flesh and Feather, published by Theion Publishing, lays his Kemetic cards on the table with his contribution, which focuses not on any music they themselves make, but on a ritual that takes the form of a conversation between Djehuty and Barbelo/Sophia. The dialogue is spread across an exhausting sixteen pages at a fairly large point size and with a lot of leading between the lines, with the words spoken by Sophia being differentiated with some hideous underlining as if we’re still living in a world of manual typewriters instead of one in which any variation of formatting could have been chosen.

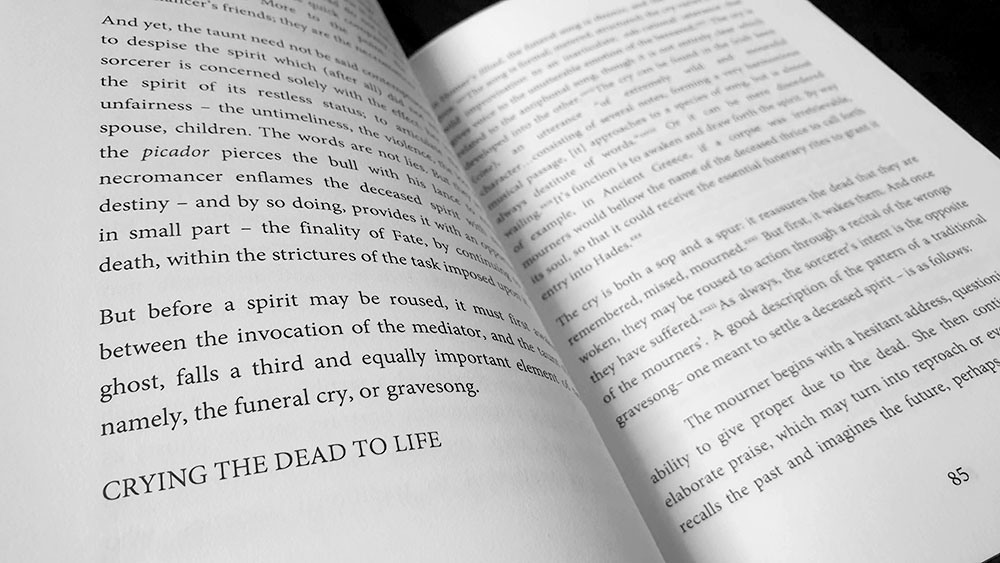

Moving swiftly along, another author, Jack Grayle, whose book on Hekate, The Hekatæon, was published by Ixaxaar, provides a dose of erudition with Gravesong. Once again, though, this piece feels a little divorced from the overall theme of this anthology, though it is tangential, with Grayle focusing on funeral songs, particularly in the intersection of Aeschylus’ trilogy of plays The Oresteia and the Greek Magical Papyri. Again, and through no fault of Grayle, the formatting here leaves a lot to be desired, with subtitles capitalised but otherwise unformatted (and in one instance, widowed at the bottom of a page), and with the endnotes kept in Microsoft Word’s deplorable default Calibri styling.

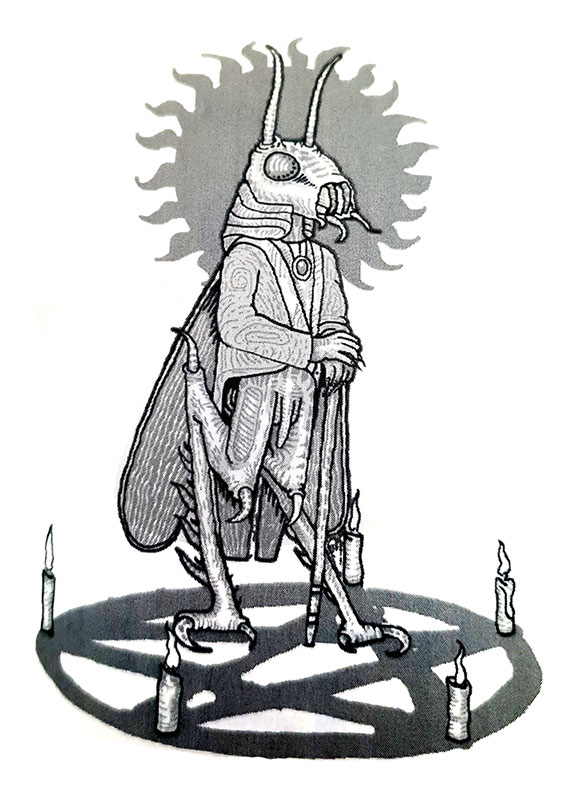

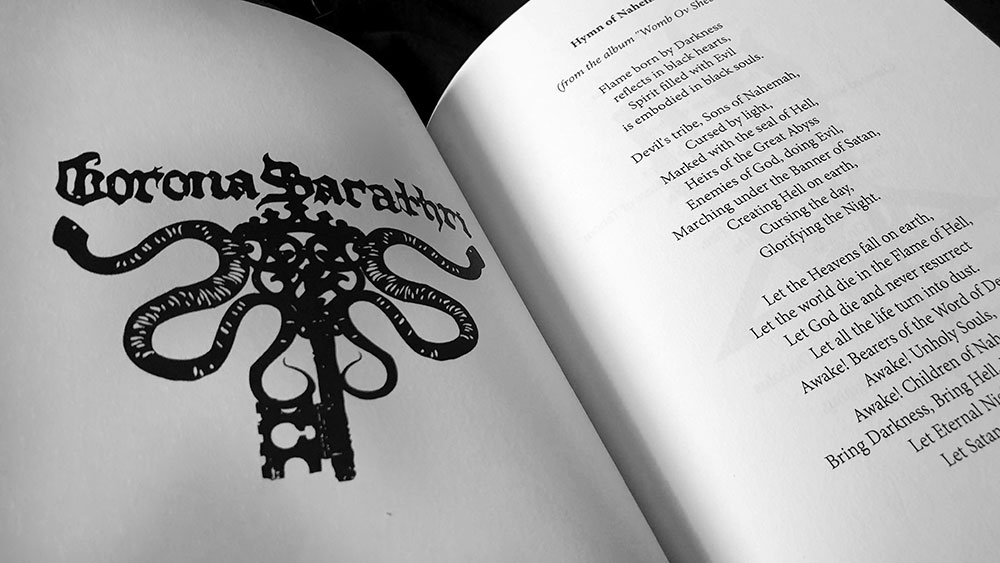

Ilya Affectvs mirrors the entry from Hvile I Kaos with a thorough, fifteen page, multi-section overview of his ritual ambient project Corona Barathri. It begins with a general biography and statement of intent, followed by Oratio Sacra, a part-manifesto sermon that is exemplary of Corona Barathri’s diabolist themes and lyrics, finally ending with the lyrics of two songs, Hymn of Nahemoth from the album Womb Ov Sheol and the title track from Speculum Diaboli.

In Baron Samhedi, Edgar Kerval gives a broad outline of his project Emme Ya before turning to the baron of the title. Ostensibly this is done to illustrate how Kerval has worked profoundly with Baron Samhedi since 2009 and how the attendant methods of invocation include sonically-induced trance states. In practice, though, this is more of a six page general biography of Samhedi with a concluding ritual, and one that could have benefited from proofing and editing to corral Kerval’s otherwise enthusiastic prose.

In Baron Samhedi, Edgar Kerval gives a broad outline of his project Emme Ya before turning to the baron of the title. Ostensibly this is done to illustrate how Kerval has worked profoundly with Baron Samhedi since 2009 and how the attendant methods of invocation include sonically-induced trance states. In practice, though, this is more of a six page general biography of Samhedi with a concluding ritual, and one that could have benefited from proofing and editing to corral Kerval’s otherwise enthusiastic prose.

A different style of writing is provided by Keeley Swete and Jessica Rose of Portland’s She Scotia with their Music as Ritual, which invites the reader to reject the commodification of music in favour of something with a more sacralised intent. This is a considered and eloquent piece with a voice that blends a New Age style of metaphysical speculation with a witchy underpinning, a little self-help, a little inspi- and aspi- rational. Jon Vermillion’s The Souls (sic) Expression Through the Universal Vibration of Sound follows and feels somewhat cut from the same cloth, with a focus on frequencies and sound waves, and visualising a violet sphere of light. There’s an obvious debt to Robert Monroe’s idea of altered conscious using audio techniques to achieve hemispherical synchronization, and quite a bit of the New Age with talk of Kryst Consciousness, meditation and etheric bodies. Sitting within the same pages as Emme Ya’s Baron Samhedi and Corona Barathri’s diabolism, this makes for some incongruent company.

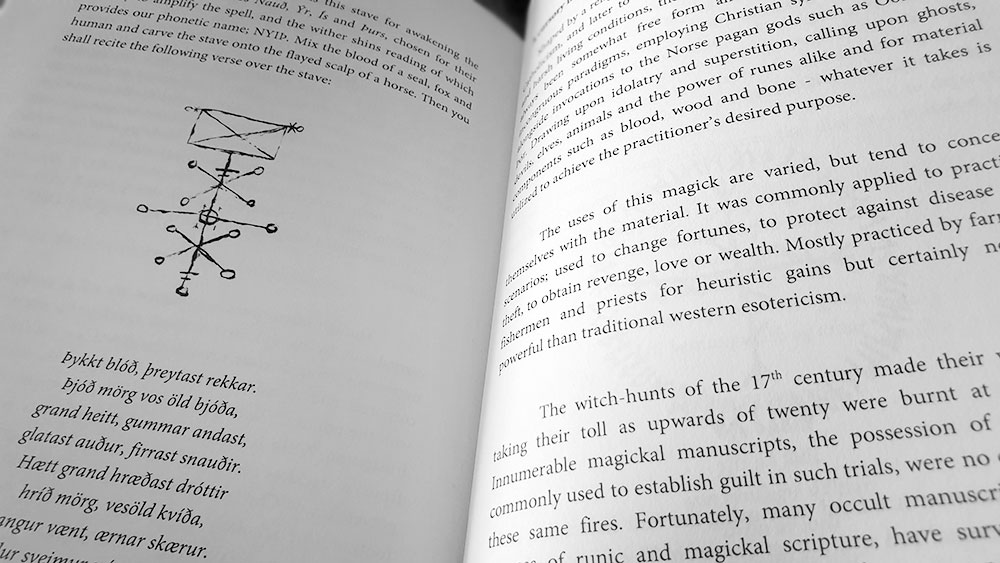

Iceland’s enigmatic NYIÞ offer one of the most interesting contributions here, situating their work within the folklore and magick of their homeland, beginning with a broad overview of such. They then pull back the curtain, explaining the symbolism behind various choices of instruments (the organ being linked to death, skin drums with shamanism, etc) and then showing how these elements can be combined with more conventional instruments and intent to create their intersection between music and magick.

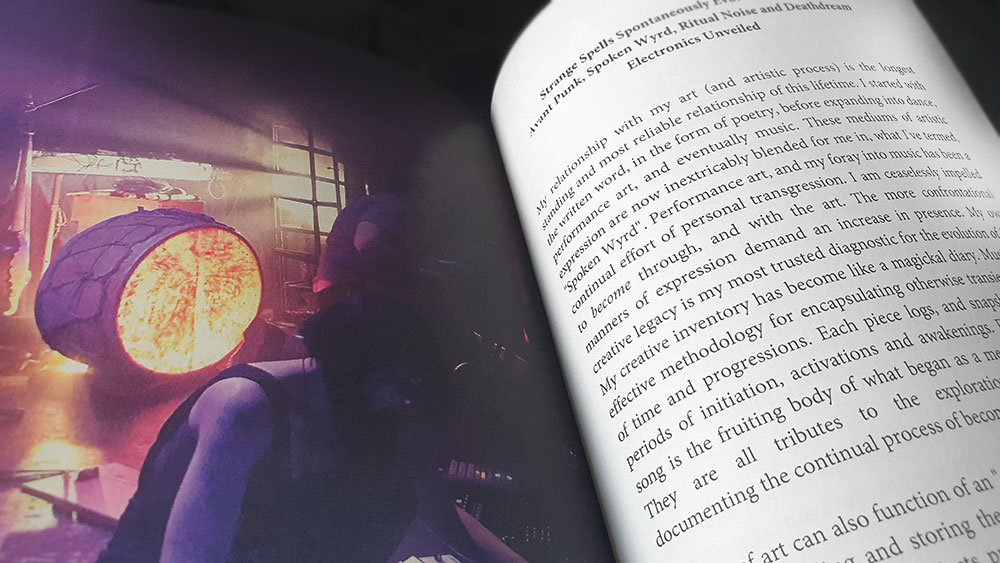

Finally, zenKOAL of the ritual noise duo Brujentropy wields the longest-titled entry here, offering Strange Spells Spontaneously Evolving into Art: Avant Punk, Spoken Wyrd, Ritual Noise and Deathdream Electronics Unveiled no less. It’s also a pretty long piece in general, with zenKOAL writing dense paragraphs in a lyrical and effusive manner that, given the abrupt and indecisive formatting elsewhere in this volume, is quite welcome and even comforting. Like a lot of the entries here, this feels like a manifesto, with zenKOAL describing her practice, both magical and musical, as one in which creative works are birthed as sentient entities that gradually form over time, and eventually perpetuating themselves independent of their creator.

In all, Music in Witchcraft and the Occult has promise but is let down by the presentation and lack of attention to detail. It is presented in an edition of 200 hand-numbered exemplars, bound in cloth with a metallic foiling of the title and a stylised flame on both the cover and the spine. There are multiple images used throughout, both graphic and photographic, with some at full page or as spreads, while others are awkwardly marooned on their own and not integrated into the text, as if they’ve retained the practical formatting of their original submission document. Accompanying the book is a CD that compiles music pieces from the various contributors: Gydja, Khtunae, She Scotia, NYIÞ, Hvile I Kaos, Brujentropy, Corona Barathri, Emme Ya and Synesect.

Published by Aeon Sophia Press