Anathema Publishing has released several works by Craig Williams, but this was the first, a relatively slight text based on the idea of the working with the theme of the desert and the solitude of monasticism. As with some other reviews of Anathema titles, this one requires a slight caveat as your humble reviewer has an editing credit here, though in my defence, time marches so inexorably forward that I often don’t immediately recall the text ‘pon reading it.

Anathema Publishing has released several works by Craig Williams, but this was the first, a relatively slight text based on the idea of the working with the theme of the desert and the solitude of monasticism. As with some other reviews of Anathema titles, this one requires a slight caveat as your humble reviewer has an editing credit here, though in my defence, time marches so inexorably forward that I often don’t immediately recall the text ‘pon reading it.

What becomes immediately apparent in reading Entering the Desert is a decisive placement of its contents in opposition, setting it, as the saying goes, against the modern world. Williams lets little time pass between moments of decrying something wrong with modernity, be it the world in general or occultism in particular. This degree of vituperative invective gets a little tiresome rather quickly, and its earnestness grates in its self-congratulatory repetition, getting in the way of good narrative as there’s almost an unspoken expectation that the reader will be hooting and hollering at each sick burn. It’s like when someone first discovers that Christianity isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, or that popular culture isn’t as cool as Hot Topic culture, or when Krusty the Clown became a tell-it-like-it-is stand-up comedian, except here the shibboleth is that nasty nasty modernity, boo, hiss.

It is, though, this opposition to the modern that acts as the primary motivation for what is presented here, with the entering of the desert being a chance to literally get away from it all. The desert is idealised as a place of isolation from the modern world, the journey to which is, as the book’s subtitle renders it, a pilgrimage into the hinterlands of the soul. Conversely, though, this is but one of what Williams identifies as two deserts, with the individual’s internal Desert of the Soul contrasting with an outer desert of the collective environment and dreaded modernity. Williams is at pains to point out that using this iconography is not an escapist fantasy or just a simple visualisation (which would, no doubt, be oh so modern), but rather a less tangible mode of being, more of a telling-it-like-it-is in which “one ruthlessly examines and accepts all the ‘aspects of life.’”

There is a practical side to all this detached examination, and in chapter two, The Cell, Williams expounds on the use of another location within this eremophilous topography. This cell is treated less as a theoretical locus than the wilderness itself, and Williams provides a broad guide to what you’re going to get up to on your lonesome.

Inevitably, what emerges here is clearly indebted to the desert fathers and mothers of the early church, at least in an aesthetic and general approach, even if the overlay is an antinomian, anti-modern, hyper-individualist one. Like those hermetic forebears, the practitioner seeks isolation from the greater world, but Williams hastens to add that there is none of the asceticism of the latter, in which the body and flesh is abhorred and mortified. Despite the preponderance of the world ‘gnostic’ there’s also none of classic Gnosticism’s distain for matter, incarnation and existence. Instead, the cell acts as a space within which to alchemically sacralise the flesh, awakening daemonic voices from within both the mind and the body. To do this, the gnostic hermit enters a unique time stream within the cell, and performs simple exercises of breathing, mediation, reading and dreamless sleep. This awakened Sacramental Vision then allows the devotee to view the desert of the world as a source of nourishment and empowerment, a reflection of the inner landscape of the Soul, and not as an existential threat.

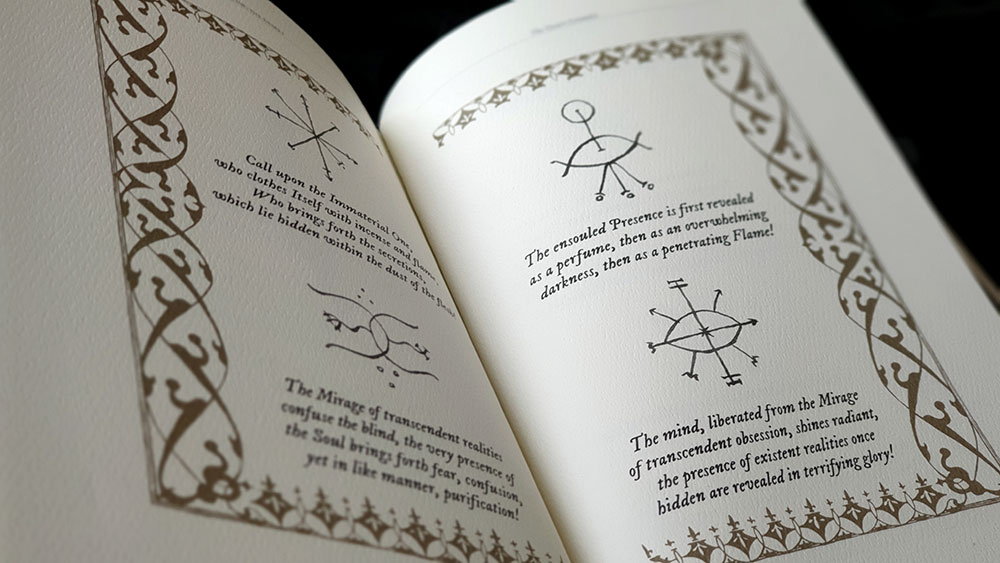

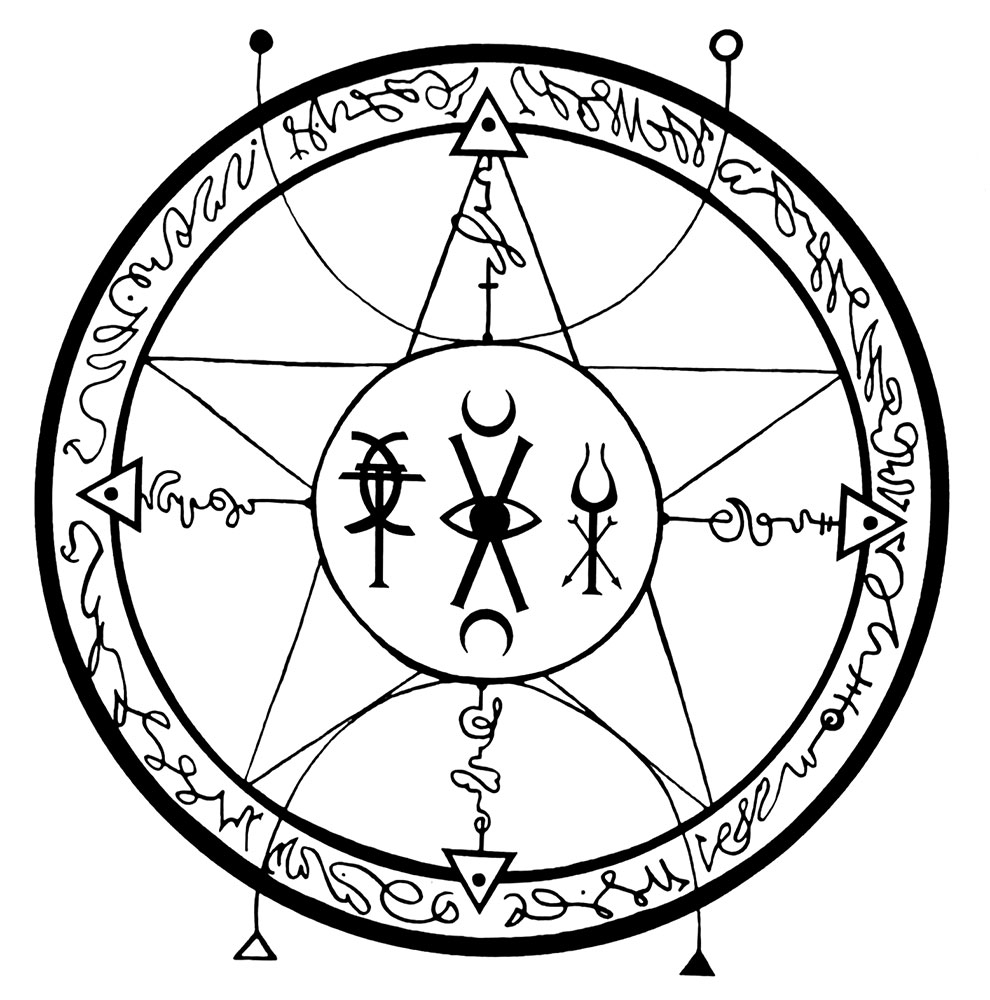

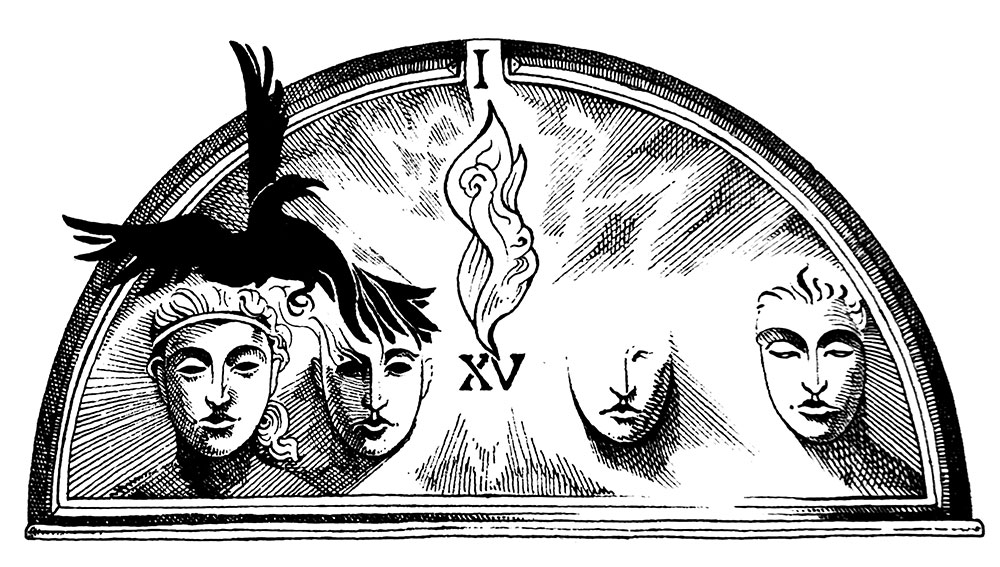

The broad outline of the preceding chapters gets more specific in a section called The Desert Grimoire, which provides exactly that, a grimoire of rituals and verse that is described as a transmission from the deeper regions of the wilderness of the soul. The first item of note is an introduction to a heretofore unmentioned aspect of Williams’ system, a group of primordial and supra-spacetime intelligences called the Priests of Night, whose egress within the cell can be initiated through the cultivation of its atmosphere. Other rituals follow, including a multi-day vigil, an invocation, and a lovely desert liturgy. The Desert Grimoire concludes with a section of verses, two to a page, each accompanied by a sigil and all wrapped within an ornate border. These provide a reification of what has been presented elsewhere in the book, but simplified into, or veiled by, poetic language.

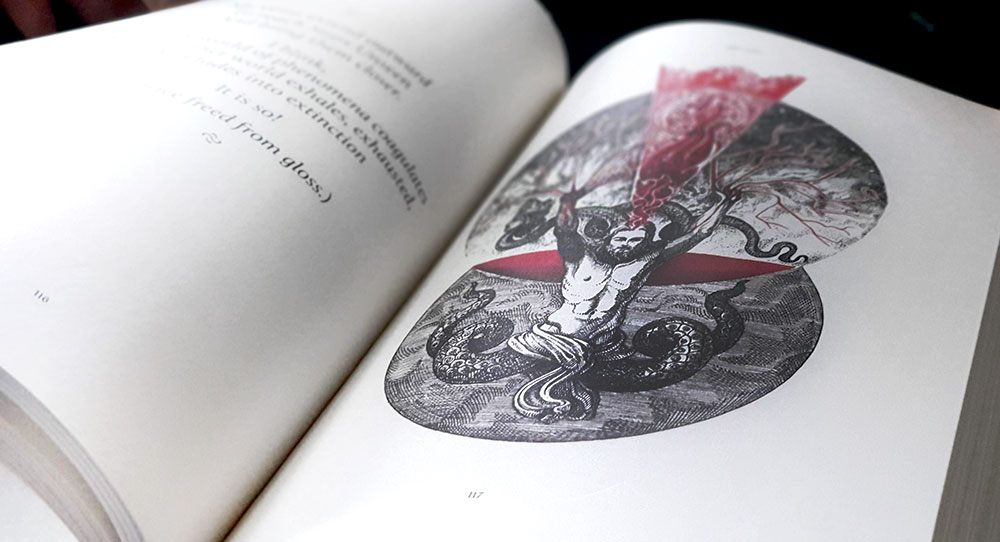

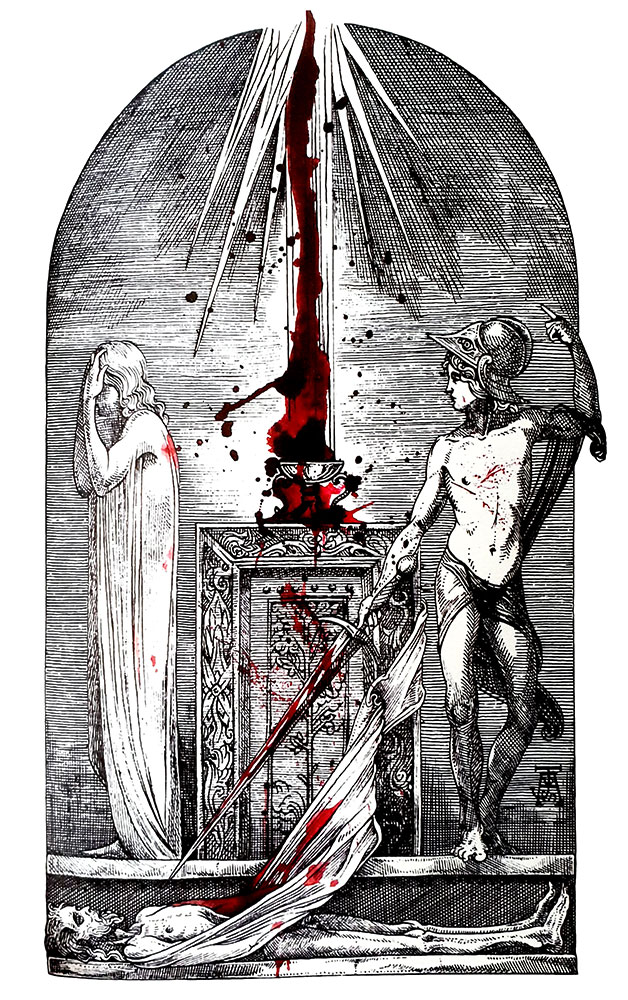

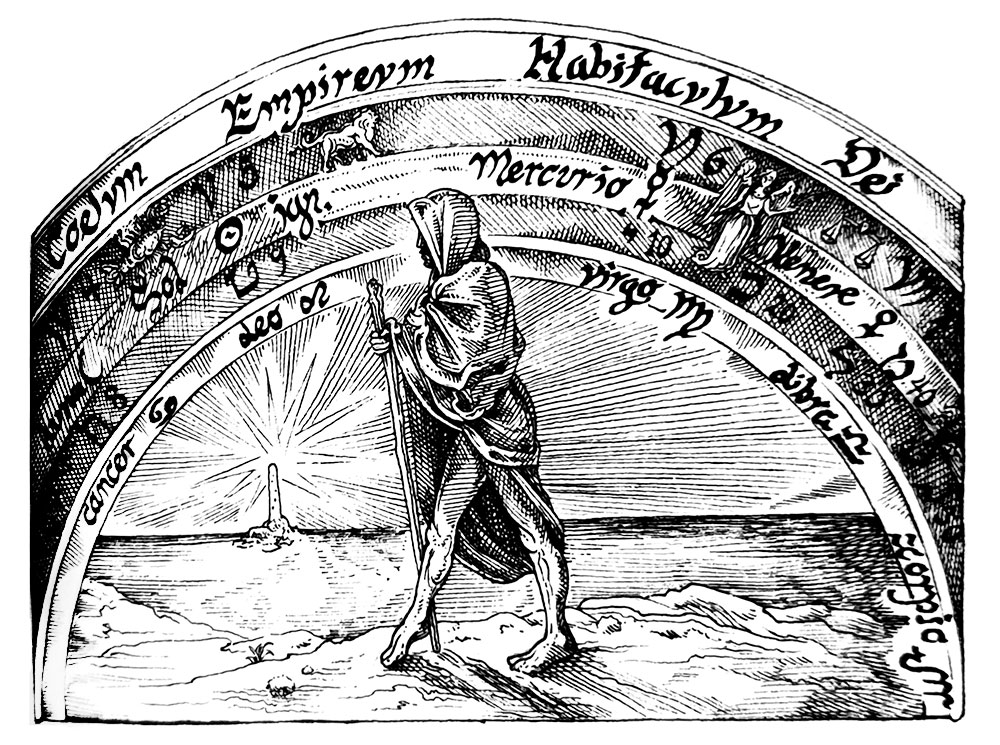

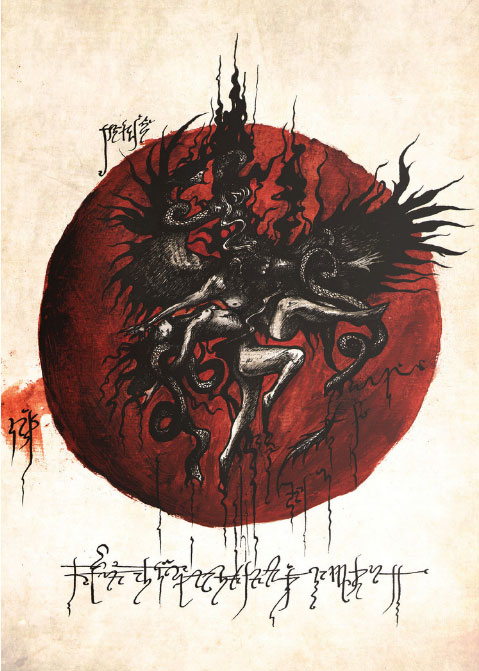

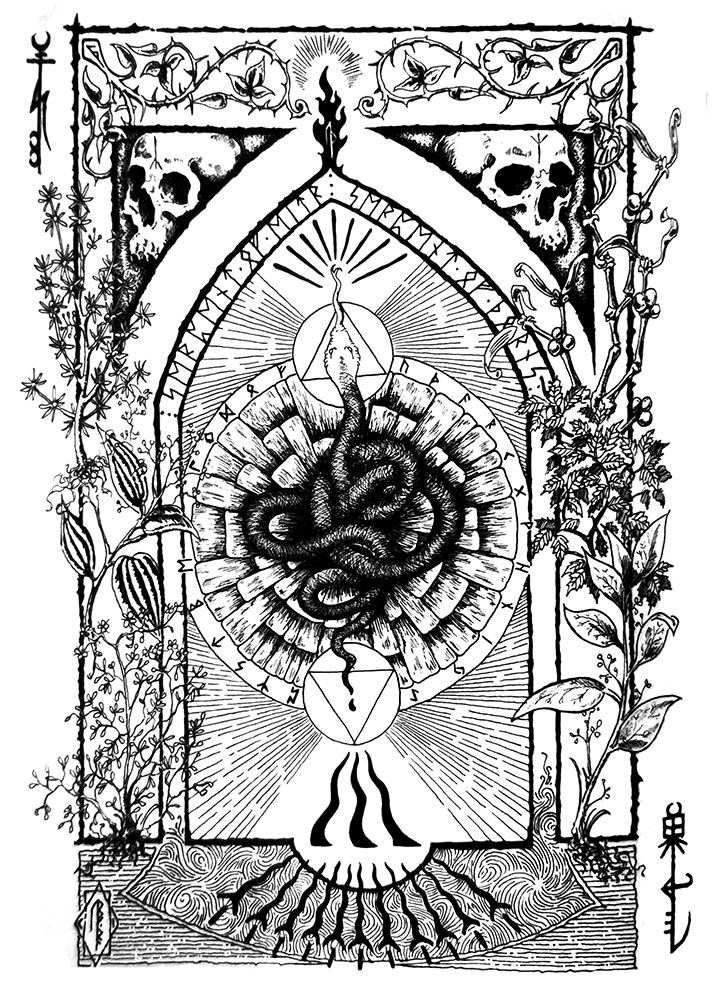

The typography in Entering the Desert is expertly executed in typical Anathema style by Gabriel McCaughry: the body set in a relatively large, fully justified serif face, with headings and quotes in a copper tint for an understated touch of visual interest. David S. Herrerias provides extensive illustrations throughout, with both paintings and pen and ink illustrations, including one painted image of the desert that acts as both the front and rear endpapers, spreading across verso and recto. The internal paintings largely follow the style of this endpapers landscape, with a sedate tableaux of muted yellow and brown tones, including a Sparesian portrait of Williams himself. The pen and ink images follow the style seen previously from Herrerias, including his previously-reviewed Book of Q’Ab-Itz, with amalgams of Andrew Chumbley-like facetted plains and jagged geometry, and spindly things breaking into space. His desolate aesthetic makes for a fitting companion to Williams’ theme, conveying the sense of an eremitic and uncanny touching of the beyond.

In all, Entering the Desert is a pleasing little tome that brings its theme together rather well in terms of written and graphic elements. At its core, it contains some rather simple or fundamental concepts, as one would expect when the matter is one of sitting alone in the desert with nothing but wraiths and strays for company, But Williams presents these in a considered, perhaps too considered, manner that patiently reiterates each theme or technique in what becomes almost its own devotional or meditative act.

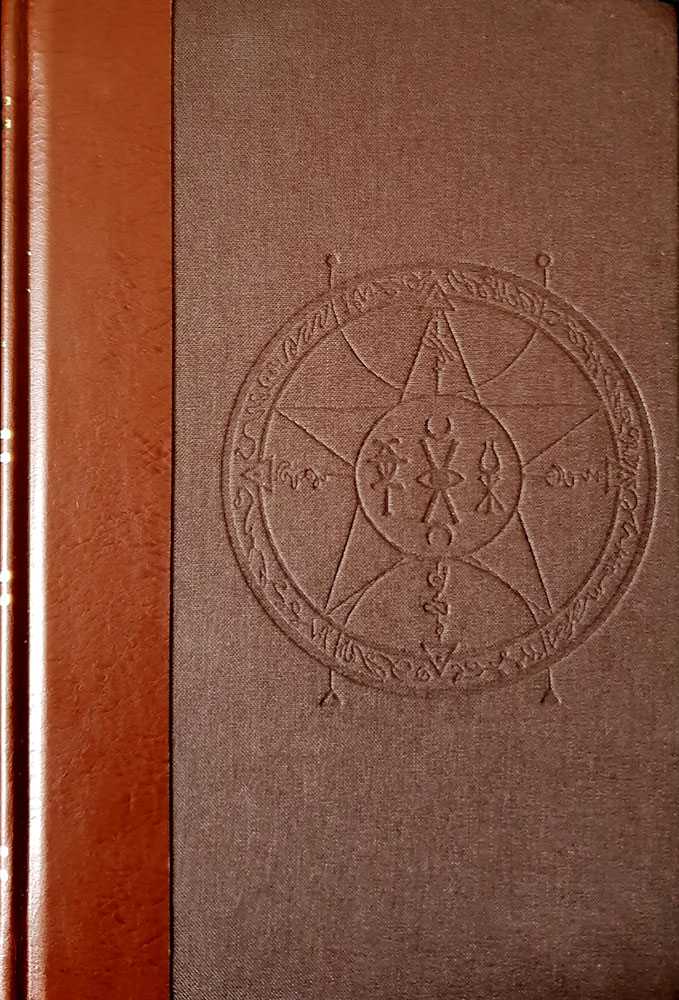

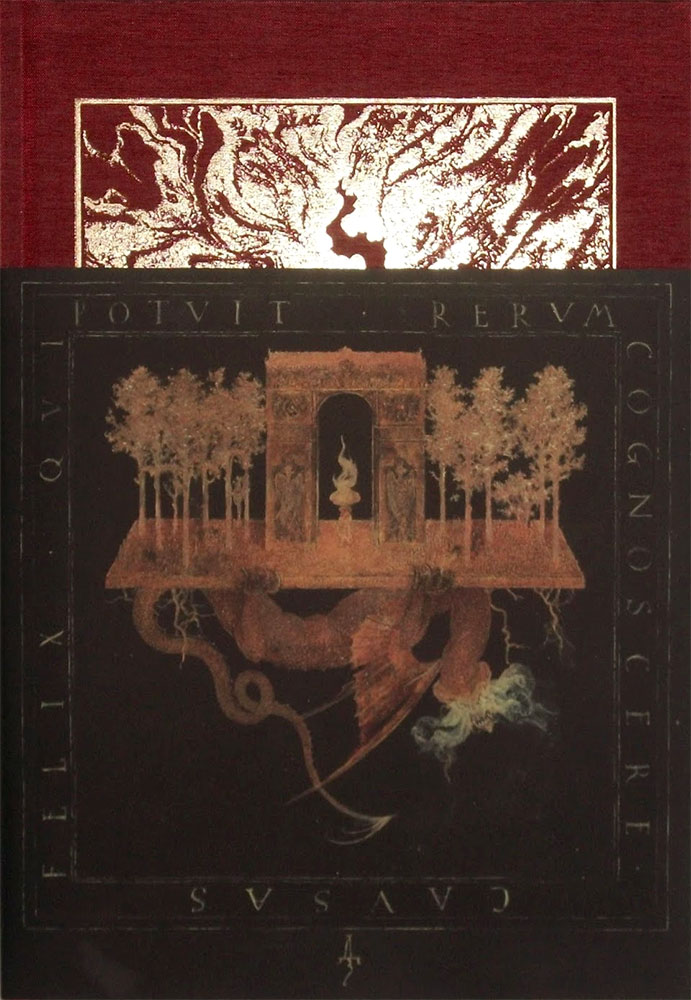

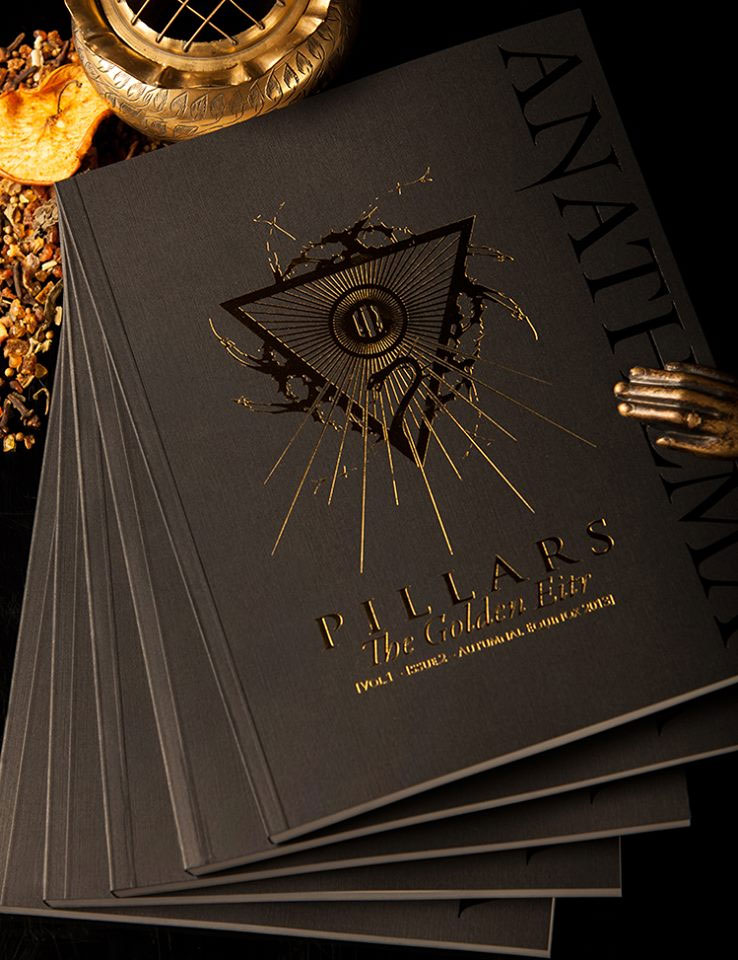

Entering the Desert was released in four editions: a paperback, along with hardback editions of standard, collector and artisanal; all three of which are now sold out. The paperback runs to 176 pages of Rolland Opaque Natural 140M quality paper, bound in a scuff-free velvet matte with a selective spot varnish on the cover. The standard hardback edition of 400 copies featured 160 pages on Royal Sundance paper, hardbound in Sierra Tan bookcloth, with the title foiled in metallic black foil stamp on the spine and slightly hard to parse phantasmagorical figures blind-debossed to both the front and rear covers.

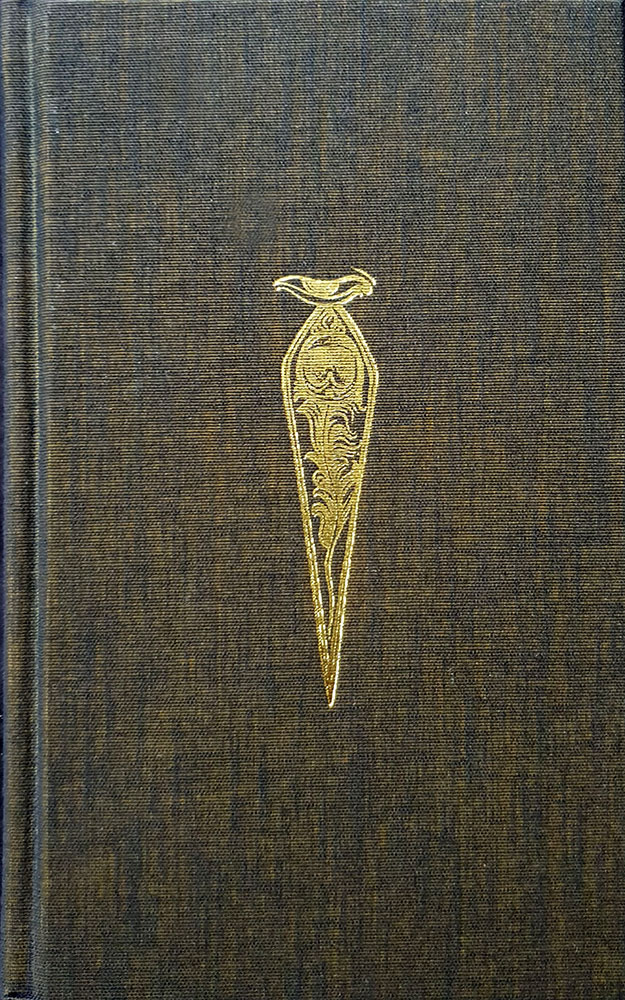

The collector’s edition of 150 copies binds the pages in a Fiscagomma Agenda dark brown faux leather, with a different symbol to the standard edition stamped in bronze foil on the cover, and metallic bronze foiling to the spine, It comes with a hand-numbered book plate signed by the author. Finally, the artisanal Midnight Sun edition of twelve copies was hand bound in genuine buffalo leather, dyed midnight blue, with a symbol blind debossed and gold foil stamped on the front cover. With custom-made artisanal endpapers and raised nerves and gold foiling on the spine, the Midnight Sun edition was presented in a slipcase bearing handmade custom-dyed marbled paper so that each box looked slightly different to the other.

Each hardcover edition of Entering the Desert also came with a download code for a copy of a musico-mystical contribution from ritual/dark ambient projects Shibalba, Alone in the Hollow Garden and Nam-Khar. These five tracks (or vibrational rituals, as they’re called here), three from Shibalba and two from the collaboration of Alone in the Hollow Garden and Nam-Khar, were channelled specifically as a meditative sound support for Entering the Desert and do have a certain eremophilous quality, casting detailed percussive sounds, throat singing and the occasionally languid Orientalist figure against linear landscapes.

Published by Anathema Publishing

The soundtrack for this release is naturally the pieces created by Shibalba, Alone in the Hollow Garden and Nam-Kar for Entering the Desert. The tracks by Alone in the Hollow Garden and Nam-Kar can be heard on the Alone in the Garden Bandcamp page.