Subtitled Reflections on Religion and Nature for a Queer Planet, Punctum Books’ Meaningful Flesh is a relatively brief anthology featuring contributions from Jacob J. Erickson, Jay Johnson, Timothy Morton, Daniel Spencer, Carol Wayne White, and editor Whitney A. Bauman. It presents a variety of musings on nature and religion, two things that, as the preface describes it, are much queerer than we ever imagined; hrmph, speak for yourself, I have some pretty queer imaginings.

Subtitled Reflections on Religion and Nature for a Queer Planet, Punctum Books’ Meaningful Flesh is a relatively brief anthology featuring contributions from Jacob J. Erickson, Jay Johnson, Timothy Morton, Daniel Spencer, Carol Wayne White, and editor Whitney A. Bauman. It presents a variety of musings on nature and religion, two things that, as the preface describes it, are much queerer than we ever imagined; hrmph, speak for yourself, I have some pretty queer imaginings.

Following a preface from Whitney A. Bauman and an introduction from Daniel T. Spencer, Carol Wayne White opens the proceedings with the longest contribution here, Polyamorous Bastards: James Baldwin’s Opening to a Queer African-American Religious Naturalism, in which she begins by highlighting Baldwin’s use of the ‘bastard’ epithet as a multifaceted expression of the black experience of marginality in North America. This she then incorporates into the idea of African-American religious naturalism, a concept she has developed before and in great depth, most notably in 2006’s Black Lives and Sacred Humanity: Toward an African American Religious Naturalism. Here, though, this African-American religious naturalism is less defined, and so the appeal to it, and its incorporation into the preceding and thorough exploration of Baldwin’s ideas, feels inconclusive, almost abrupt.

A highlight here is Jacob J. Erickson’s Irreverent Theology: On the Queer Ecology of Creation which uses as its starting point Isabella Rossellini’s Green Porno series of short films on animal sexual behaviour. Indeed Rossellini does much of the work early on, with the preamble consisting of a recounting of her gentle and whimsical excoriation of the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, in which the divine directive of male and female animal pairs is rendered foolish by the queer diversity of gender within the animal kingdom. Erickson incorporates an overview of Karen Barad’s theory of agential realism from her 2007 book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, seeing her writing as key in the way it mutually-enhances and collaborates with the insights of queer theory, philosophies of science, and ecology. Pursuing Rossellini’s observation that “Nature is infinitely scandalous,” Erickson uses Barad’s idea of nature as post-humanist performativity to uncover a delightful and profound queerness in Martin Luther’s incarnational theology of creation, in which creatures are considered larvae dei (‘masks of God’) or involucrum (God’s ‘wrapping’). Acknowledging the ‘burlesque attitude’ with which Luther approaches theological language, Erickson argues that this use of carnivalesque masks of God effectively casts the divine as something “caught up in a kind of queer performativity of the earth,” wherein it desires to play and revel in its grounding.

Jay Emerson Johnson mines a similar vein to Erickson with Liberating Compassion: A Queerly Theological Anthropology of Enchanting Animals, in which, informed by queer theory’s suspicion of binary classification, he muses on what defines an animal and a human, noting the way in which both scholar and lay so easily assume an often hierarchical distinction between human and animal, one that mirrors similar Western assumptions about sexually gendered categorisation. As an explication of these themes, Johnson examines the multiple performativities in ecosystems of gay affection most specifically in the fetish of human-pup-play. This thinning of classifications is then applied to theology, with Johnson suggesting that the dissolution of the idea of the imago Dei as the sole preserve of ‘humans’ would lead to “an awareness of other-than-human pain and suffering, or empathy.”

In the penultimate entry, Queer Values for a Queer Climate: Developing a Versatile Planetary Ethic, Whitney Bauman follows the contributions that precede him with an attempt to decentre anthropocentrism in the perception of nature and thereby create new forms of performance that re-engage with/on/in the planet by respecting its agency at multiple levels. Like Johnson before him, Bauman embraces queer perspectives in order to create a better way of viewing the world, taking cues from Jack Halberstam’s call for an ethics of ambiguity and unknowing rather than progress, Timothy Morton’s call for a queer ecology or “ecology without nature,” as well as a queering of our sense of linear time. As Jacob J. Erickson did earlier, Bauman also draws attention to the queerness of gender and sexualities amongst the animal kingdom, referencing Joan Roughgarden’s book Evolution’s Rainbow to show how heteronormativity has been read into the evolutionary record by those doing the reading. For Bauman, then, a better world is one unshackled from hierarchies of time, and the unassailable, inexorable destiny of progress or the heteronormative nuclear family, replaced by an understanding of a reverberating and non-teleological time that cultivates “an ecology of relationships that stretches across multiple generations and multiple terrains” akin to a Deleuzian rhizome without beginning or end.

Bringing everything to a meaningful and fleshy end is Timothy Morton, who, would you believe, provides a reflection on queer green sex toys in order to challenge the ontology of agrilogistics. Um, yes. What that means in practical terms is perhaps less salacious than one might hope, with each of the words acting as a heading for various philosophical musings. Queer considers the metaphysics and epistemology of perception in which anything, be it a frog, a meadow or climate change is impossible to purely define and must therefore, and paradoxically, not exist at all. Green builds on this philosophical conceit to define agrilogistics, Morton’s idea of agriculture as a virus, running since about 10,000 BCE when hunter-gatherers settled down and farmed grain, whose three axioms are the law of noncontradiction is inviolable, to exist is to be constantly present, and more existing is better than any quality of existing. As for Sex, which, not unexpectedly, cannot be limited to just one heteronormative expression within a ‘gigantic ocean’ of sexualities and gender, Morton defines it as an ontologically fundamental category like queer and green, as the uncontainable enjoyment that occurs when the first two categories begin to resonate in an enjoyment that implies movement. These queer, green sex beings are finally categorised as the toys of the title, being contingent, fragile, and most significantly, playful; for to play is to make violable the first axiom of agrilogistics: the law of noncontradiction. For Morton, then, thinking ecologically is not an exercise in themes of normative purity and eternal truths, but rather an understanding that things are queer green sex toys.

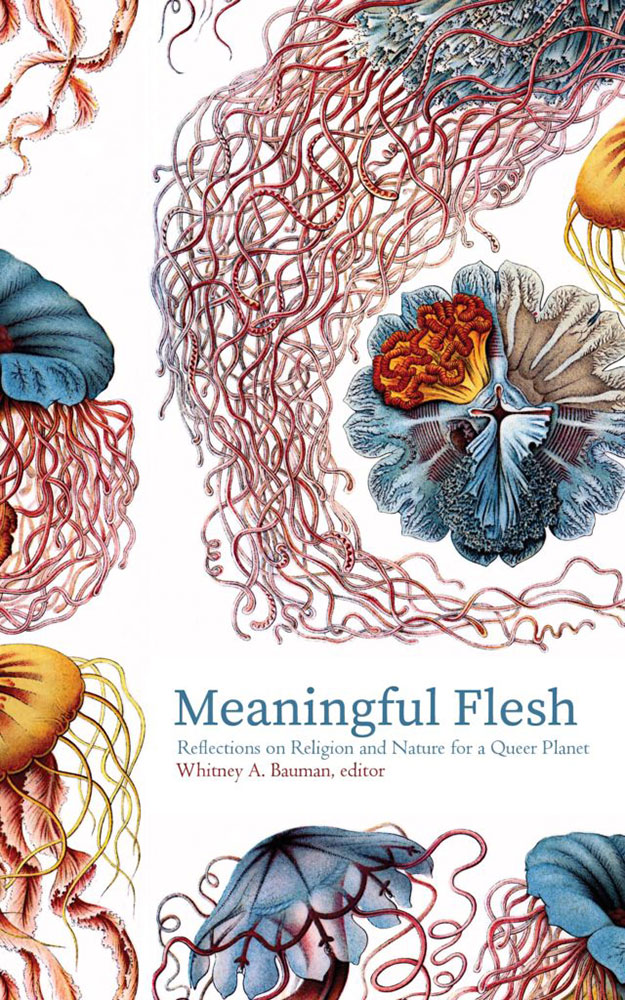

With its five entries, Meaningful Flesh provides a little something for everyone so inclined, with certain themes that run through each pieces, especially the last four, in which the queerness of nature is a central tenant. Also, the cover design by Chris Piuma incorporating images from Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur is lovely.

Published by Punctum Books