Published in 2014 by the Punctum Books imprint Dead Letter Office (home to “work that either has gone “nowhere” or will likely go nowhere”), this is a suitably appropriate paean to prolific sound artist and noise musician Stanley Keith Bowsza, better known as Minóy. A significant figure in the mail art and noise scene of the 1980s, Minóy produced over a hundred works before abandoning music in the early 1990s. Following his death in 2010, the collection of Minóy master tapes was entrusted to musician, past collaborator and long-time fan PBK (Phillip B. Klingler) who now curates the reissuing of these releases via Bandcamp.

Published in 2014 by the Punctum Books imprint Dead Letter Office (home to “work that either has gone “nowhere” or will likely go nowhere”), this is a suitably appropriate paean to prolific sound artist and noise musician Stanley Keith Bowsza, better known as Minóy. A significant figure in the mail art and noise scene of the 1980s, Minóy produced over a hundred works before abandoning music in the early 1990s. Following his death in 2010, the collection of Minóy master tapes was entrusted to musician, past collaborator and long-time fan PBK (Phillip B. Klingler) who now curates the reissuing of these releases via Bandcamp.

Being a Dead Letter Office release, Minóy is not a long work and is comprised of essays almost entirely by editor Joseph Nechvatal, with the exception of one by Amber Sabri. Sabri’s piece is a prelude, in turn, to the visual component of Minóy, featuring a selection of images she took of Bowsza in the 2000s. This creates an interesting contrast, as Nechvatal’s writing is frequently dense and academic, while Sabri’s memoir is, by its nature, more personal and informal, and her images provide the only visual evidence within of the book’s subject.

Nechvatal kicks things off with the gloriously verbose title that is The Saturated Superimposed Agency of Minóy, which provides a thorough biography of Minóy and his work, before descending into considerably more philosophical territory. He draws attention to the echoes of La Monte Young in Minóy’s use of length as a compositional technique, arguing that the extended length allows deep subjective perceptions of the present moment to come to consciousness, thereby offering “a sonically ontological vision of the world as superimposition, one that shows us in place inside of a saturated world.” This idea of noise in general and Minóy’s in particular as a queer-like force that acts in resistance to conformity and mundanity, is one that permeates Nechvatal’s writing here. He doesn’t employ the lexicon of queer theory, though, using instead his own language of hypernoise theory, often referring to the ability of Minóy’s music to create an interplay of the human and the nonhuman.

Nechvatal concludes The Saturated Superimposed Agency of Minóy with an addendum in which he provides reviews of a mere eight of Minóy’s works, culled from a variety of sources and writers, principally Sound Choice but also Lowlife and Option magazines. For those unfamiliar with Minóy’s output, these give a sense of the soundworlds he was creating, and more importantly, how they were perceived by his contemporaries.

In Whatever Happened to the Man Named Minóy? Sabri writes a memoir of the man she knew, not as Minóy but as My Life as A Haint. By becoming a haint, a term used in the vernacular of the southern United States to refer to a ghost, apparition or lost soul, Bowsza drew a line under the Minóy that had obsessively created music for a decade and instead, now largely bed-ridden with physical and mental illness, turned to digital art as a form of expression. There’s something in the use of the word haint that evokes Mishima’s description of slipping through life as a ghost, sitting on the outside and divorced from convention. This is evidenced in Bowsza’s work as both Minóy and as Haint, and his personal life, in which he was divorced from confines both societal and temporal, with persistent agoraphobia and a tendency to sleep little and work long (sometimes staying awake for days on end in manic marathons of creativity).

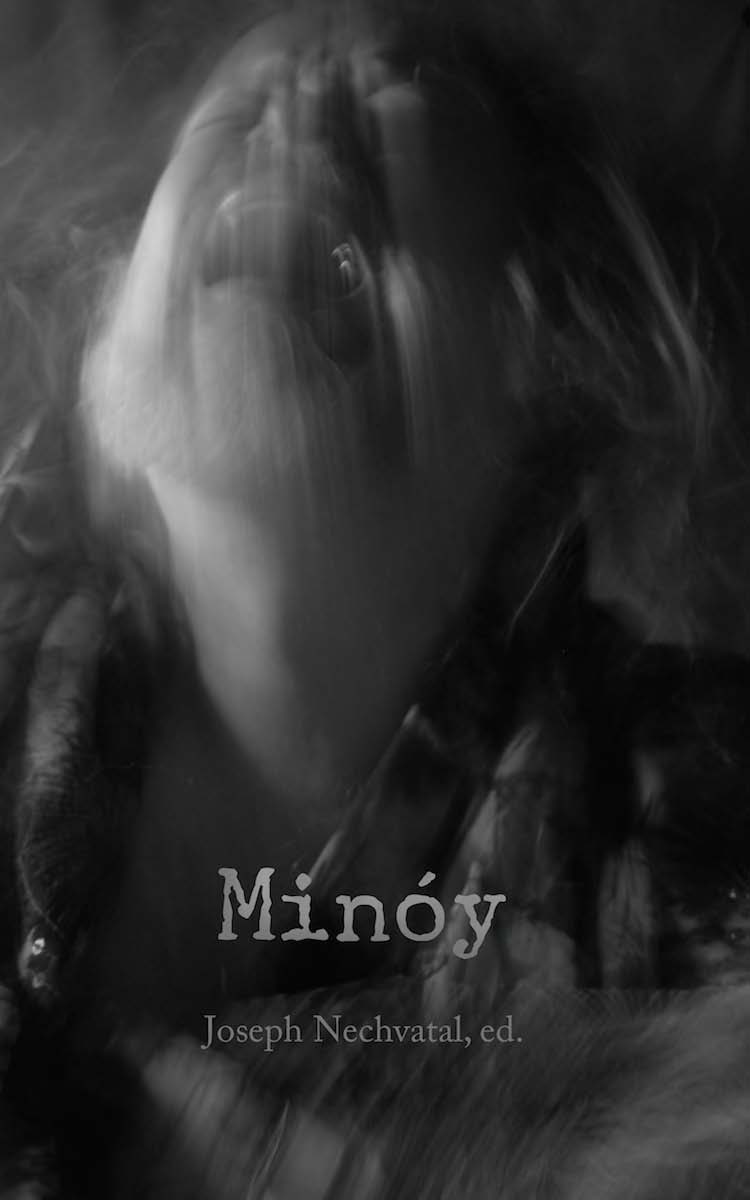

Sabri’s photo essay, credited to her glorious pseudonym Maya Eidolon and created in collaboration with Bowsza and his partner Stuart Hass, is tortuously called Minóy as Haint as King Lear and shows Minóy/Haint as Shakespeare’s titular character in 60 black and white images, presented two to a page. Framed horizontally and largely with only head and shoulders showing, the images convey a sense of psychotic ferocity, with Bowsza moving in and out of great washes of long-shutter speed blur, abstracting into clouds of movement until briefly emerging again, as if from water, with recognisable, anguished features. While the images convey in strict representational terms of sign and signifier what one would expect the whirl psychosis to look like given form, there are other questions here, concerned primarily with identity and its loss. Sabri’s title conveys this with its cast of three characters, and within these images the trinity of Minóy, Haint and Lear all appear to be asking Lear’s own question: “Does any here know me? This is not Lear. Does Lear walk thus? Speak thus? Where are his eyes? Either his notion weakens, or his discernings are lethargied – Sleeping or waking? Ha! Sure ’tis not so! Who is it that can tell me who I am?” Nechvatal’s response to Sabri’s images makes similar observations, arguing that rather than seeing Bowsza’s performance for the camera as “a descent into the thick eerie nonhuman,” it is instead an illustration of “a very specific way of living mad in the intensified flow of superimposed becoming” before tying the ferocity of the images back to the musical leitmotifs of Minóy: “we can almost hear in these images his Lear-like scream into an unbounded white noise.”

As befits Minóy’s elongated musical forms, Nechvatal continues his own musing on Minóy with an addendum, The Obscurity of Minóy, which, it transpires, is but the first of several afterwords. Like the never-ending ending to the cinematic incarnation of Return of the King, this continues with the amusingly-acknowledged After After Words of The Aesthetics of an Obscure Monster Sacré and the After After After Words of Hyper Noise Aesthetics. Indeed, these after (after after) words from Nechvatal take up more space than his main contribution, allowing him to take flight with his philosophical notions of noise.

Now we must turn to the de rigueur justification for reviewing a book on a noise musician on a site ostensibly concerned with occult titles. While there is little in Minóy’s themes, both musical and titular, that suggest the magickal or the mystical, it is the response to this music that offers almost inevitably an interpretation arcane and anagogic. PBK’s documented enthusiasm for Minóy’s work after first hearing it has something of the religious and ecstatic about it, memorialised here with his description of it as “dream-like, nightmare-like, but also sometimes spiritual.” Similarly, Nechvatal’s use of philosophical and theoretical models inevitably leads to language that is redolent of the exploration of the unconscious and the internal, of intersections betwixt the mundane and the mystical. Like PBK’s description of Minóy’s music as both nightmarish and spiritual, Nechvatal frequently invokes the figure of the monstre sacré, using it a description of Minóy himself, and often of noise music in general.

If there is a voice that’s missed here it’s that of PBK, whose recently adopted role of Minóy archivist and legacy documenter has made him a significant player in the current revival of interest in his oeuvre. While PBK is heard here and there, variously quoted and paraphrased in Nechvatal’s pieces, there is nothing of whole cloth by him here, which seems a shame.

A similarly-titled album was released to coincide with the Minóy book, featuring nine compositions from between 1985 and 1993. Drawn from recently discovered archival material, the selection was made by Nechvatal, in collaboration with PBK, with the latter remastering the tracks. Given the long-form nature of much of Minóy’s work, PBK and Nechvatal had the difficult task of finding complete works that were varied enough and short enough to fits on a single CD and still be representative of his music. The CD version of Minóy is still available at time of writing but a fittingly limited edition cassette run is sold out.

Published by Dead Letter Office/Punctum Books