Like Claude Lecouteux’s recently reviewed Mysteries of the Werewolf, Tales of Witchcraft and Wonder, this work was originally published in French and here receives its first English edition, with Inner Traditions giving it the hardcover treatment, wrapped up nicely in a green dustjacket. Like the previously reviewed title, this is an anthology of source material, but this time Lecouteux is joined by his wife, Corinne, a translator specialising in tales and legends.

Like Claude Lecouteux’s recently reviewed Mysteries of the Werewolf, Tales of Witchcraft and Wonder, this work was originally published in French and here receives its first English edition, with Inner Traditions giving it the hardcover treatment, wrapped up nicely in a green dustjacket. Like the previously reviewed title, this is an anthology of source material, but this time Lecouteux is joined by his wife, Corinne, a translator specialising in tales and legends.

Interestingly, comparing the new title with that of the 2013 original, Contes, Diableries et Autres Merveilles du Moyen Age, only the ‘wonder’ now remains, with the diableries being replaced by the slightly more palatable witchcraft. As one might expect, then, this new title is somewhat of a misnomer as the witchcraft content within these pages is so slight as to be effectively negligible. Even a section on devils and magic concerns itself with general legends of diabolism with not a single witch amongst its cast of characters. Instead, these tales of wonder run the gamut of folklore, divided into fairly self-explanatory chapters that cover off animal tales, oddities and wonders, deviltry and spells, the supernatural spouse, both licit and illicit love, wisdom and stupidity, and heroic legends. Indeed from the pleasant alliteration of the title it is ‘wonder’ that is the operative word here, with the entries often being examples of medieval miracula and mirabilia, popular narratives of the fantastic that, as Les Lecouteux note, were often mined by romance writers of the Middle Ages to form their own tales. Applying Caroline Bynum’s seminal definition of the terms, these tales are examples of mirabilia, in that the detail “natural effects we fail to understand,” and miracula, that is, “’unusual and difficult’ events… produced by God’s power alone on things that have a natural tendency to the opposite effect.” Also puzzling is the book’s subtitle, The Venomous Maiden and Other Stories of the Supernatural, given that said tale, concerning a maiden fed poison her entire life in order to become a vehicle for revenge, is hardly the most representative entry here.

In their introduction, Les Lecouteux provide an overview of the types of tales within, categorising them into five types: legends of the dead, demonic legends, historical legends, Christian legends and etiological legends. In an important caveat, they mention that to present these tales verbatim would be only of interest to specialists, so all of them have been rewritten into a consistent manner, free of redundancies and tedious appeals to God’s mercy and omnipotence, as was the style of the times. This creates a readable narrative with Jon E. Graham’s translation also flowing freely and complimenting the text nicely.

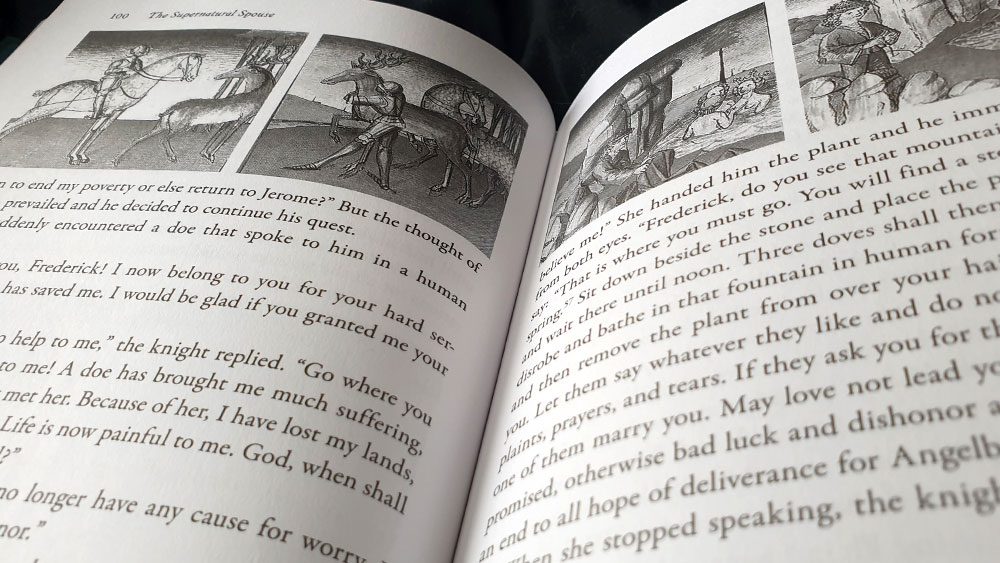

The first section with its examples of animal tales is the shortest at a mere six entries, though stories in which animals appear as the spirit forms of people do bleed into the following chapter on various oddities and wonders. One of the longest sections concerns the idea of the supernatural spouse, but there are few entries, with each of the tales being exhaustive retellings of medieval legends of courtly love, including those of Seyfried von Ardemont, Frederick of Swabia, and two swan knights, Aeneas and Helias. A similar thing occurs in the heroic legends chapter where many of the pages are devoted to single entries variously retelling the stories of Velent (Völundr) from Þidrekssaga af Bern, the anonymous 14th century romance Valentine and Nameless, and the hagiographic legend of Saint Oswald.

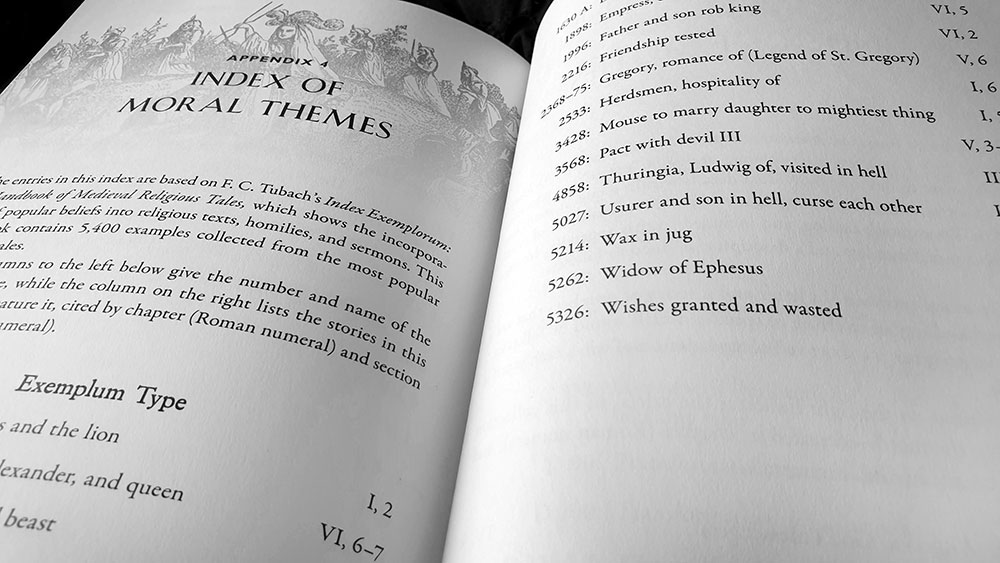

A source of frustration mentioned ad nauseam in the review of Claude Lecouteux’s Mysteries of the Werewolf was that title’s lack of contextual information and referencing, with all the entries largely adrift in terms of time, space and authorship. Mercifully, that is not the case here, and indeed Les Lecouteux appear, intentionally or not, to have made up for the omissions in the previous work with a veritable surfeit of supplementary information. Every entry has a listing of the source, one that more often than not is also footnoted to point to the particular edition in the bibliography. Not only that, but almost all of these tales conclude with an italicised explanation by Les Lecouteux, citing provenance, influence or elucidating themes and motifs. The thoroughness does not end with these though, and Les Lecouteux provide an extensive appendix of various folk tale type classifications, including Antii Aarne’s numbered system from The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and a Bibliography, the moral themes of F. C. Tubach’s Index Exemplorum: A Handbook of Medieval Religious Tales, and the extensive index of motifs from Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature. Keys to these indices appear at the end of many, though by no means all, of the entries. The inclusion of such classifications is a valuable tool and while the cross-referencing of these indexes may be limited to folkloric specialists in its usefulness, its inclusion is unobtrusive and can be ignored if simply reading for pleasure or general research.

All in all, Tales of Witchcraft and Wonder has much to recommend it as a compilation of well referenced medieval legends. The text design and layout by Debbie Glogover presents the work in a pleasant fashion, with the body text set in Garamond, minor headers in Gill Sans and Myriad, the antique NixRift for the header of each entry, and Shango, based on F.H. Schneidler’s elegant classical serif Schneidler Mediaeval, for the main and chapter titles. A feathered woodcut image sits behind each chapter heading, a various smaller images, of varying reproduction quality, are spread throughout the body of the text to keep things interesting.

Published by Inner Traditions