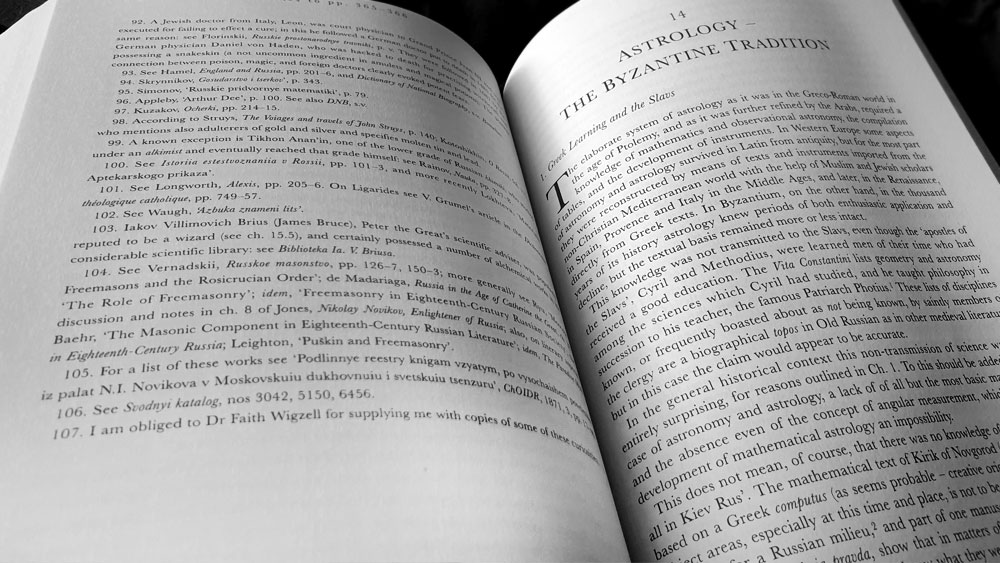

Yet another entry in Pennsylvania State University Press’s expansive Magic in History series, the peculiarly-titled The Bathhouse at Midnight is a rather weighty and encyclopaedic tome, running to over 500 pages, albeit with a significant slice of this page count being inflated by the large selection of endnotes with which each chapter concludes. William Francis Ryan explains in an introduction that the work builds upon material that they began collecting for their 1969 doctoral dissertation on Old Russian astrological and astronomical terminology, as well as a series of articles on the history of science and magic text in Russia. Suffice to say, it seems that Ryan collected quite a bit of material during this career-spanning hunt, now distilled into fifteen chapters covering off almost every field of magic conceivable.

Yet another entry in Pennsylvania State University Press’s expansive Magic in History series, the peculiarly-titled The Bathhouse at Midnight is a rather weighty and encyclopaedic tome, running to over 500 pages, albeit with a significant slice of this page count being inflated by the large selection of endnotes with which each chapter concludes. William Francis Ryan explains in an introduction that the work builds upon material that they began collecting for their 1969 doctoral dissertation on Old Russian astrological and astronomical terminology, as well as a series of articles on the history of science and magic text in Russia. Suffice to say, it seems that Ryan collected quite a bit of material during this career-spanning hunt, now distilled into fifteen chapters covering off almost every field of magic conceivable.

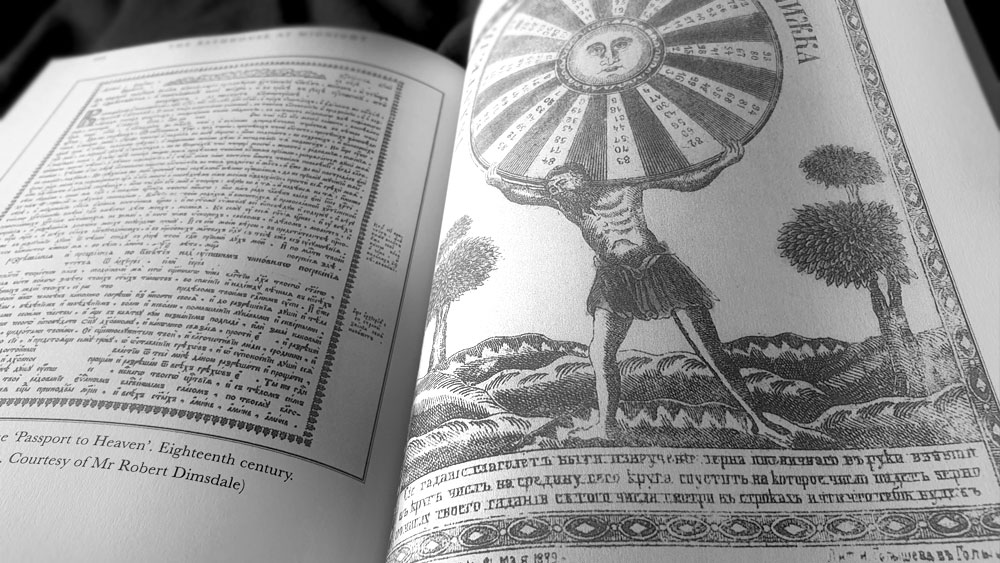

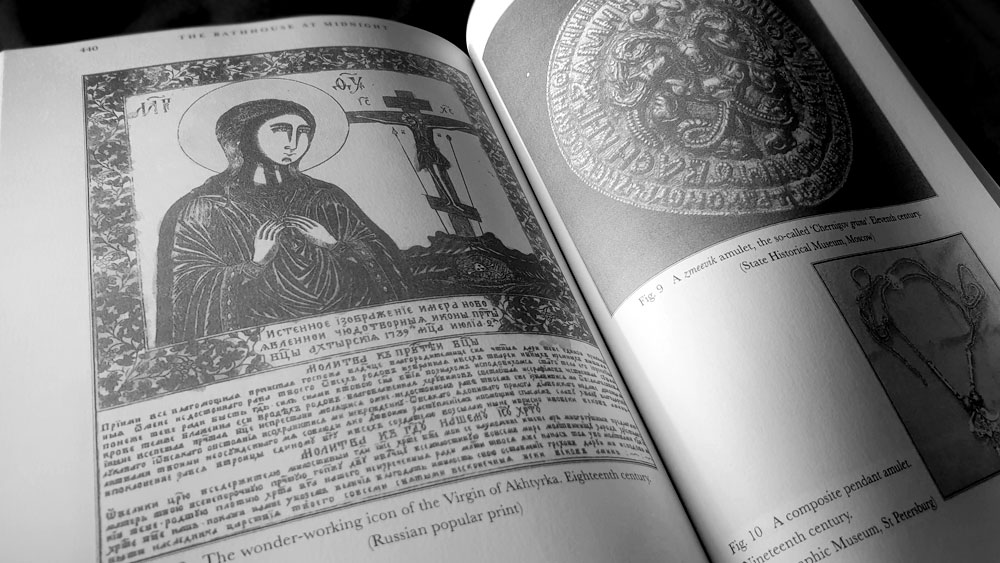

These chapters broadly divide Russian magic and divination into various subcategories, beginning with popular magic, and followed by considerations of different wizards and witches, systems of divinations, omens, predictions from dreams and physiological phenomena, spells, talismans, materia magica, bibliomancy, numerology, geomancy, alchemy, and astrology. Ryan concludes with a chapter on the relationship between magic and the church, the law and the state, and includes a roster of witchcraft cases that the Synodal court dealt with in the eighteenth century.

Ryan begins this trip to the bathhouse at midnight with an historical outline, a large part of which is effectively a literature review, albeit not of comparable scholarly dissertations, but of the source texts upon which much of Russian occultism was based. Ryan shows how a considerable body of material imported into Russia was influential on later occultism, with streams coming from an older Byzantine textual tradition, a corpus of translation from Hebrew that were originally made in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as well as more obvious Western influences. In so doing, the Russian tradition is situated within a broad occult context, wherein the confluence of similarities between indigenous and exotic practices and influence makes it hard to determine what exactly constitutes something that may have originated in native practice.

The next two chapters focus on practices and the practitioners of magic respectively, beginning with a comprehensive discussion of various types of popular magic, categorised into sections on the evil eye, malefic magic, entities such as ancient gods and evil spirits, prophylactic magic, festivals and other propitious times or dates, magical places and directions, and finally religious parody and inversions. This amounts to a covering off of all the usual areas that one might find in a contemporary practical magical text, but in this instances, there’s a lot more detail and provenance, with Ryan meticulously referencing all his sources. With the following chapter’s focus on the practitioners of this magic, Ryan provides a catalogue of these various types, dedicating usually at least two pages to discuss the Volkhv, the Koldun, the Ved’ma, the Znakhar’, and the Vorozhei. These are only the main designations, and Ryan follows with an additional section exhaustively documenting all the words used for both types of magic and their practitioners. As elsewhere, this is no perfunctory list, and Ryan lists sources, derivation and context.

This is a formula that Ryan uses throughout, everything is so detailed and draws from a wide range of sources, all tied together with an expert voice and clear familiarity with his subject. Evidence of this is the consideration of materia magica, in which Ryan provides a lengthy and useful roster of plants, both real and fantastic, used for magic rites and in Russian folk medicine, where herbs dominated. There are nine pages here, with 49 plants described with varying levels of details, some with botanical names identified, and others with merely the places they are mentioned and their purpose.

With his background as a president of the Folklore Society and an emeritus professor and honorary fellow at the Warburg Institute and the University of London, Ryan is well equipped to not only deal with the subject of this volume but to authoritatively draw comparisons with Western magic, as well as its classical roots. This makes for a comprehensive work, one that is thorough in its specificity but is aware of a broader context within the occult milieu. Because of Ryan’s readable manner, The Bathhouse at Midnight can be read sequentially from cover to cover, but is also clearly organised in such a way that allows for simply dipping in as a reference.

The Bathhouse at Midnight is formatted in the academic style one would expect of a publisher like Penn State Press with a small but readable typeface throughout and an even smaller point size for the references and index, suggesting that with less frugal formatting it could have been a work significantly longer that its 504 pages. At first glance there is one exception to the quality of the layout with a distractingly small safety area on the top margins on each page, meaning that the page title and page numbering in the header sit a mere 3mm from the edge of the page. The digital preview version on Amazon features a more comfortable margin and a closer inspection shows that printing is provided by print-on-demand service Lightning Source, whose lackadaisical quality control has resulted in a tiny top and a big bottom. Therefore it is worth bearing in mind that this book may be printed on demand and so the results may vary, for the fault, dear Brutus, is not in the layout but in the printing.

Published by the Pennsylvania State University Press