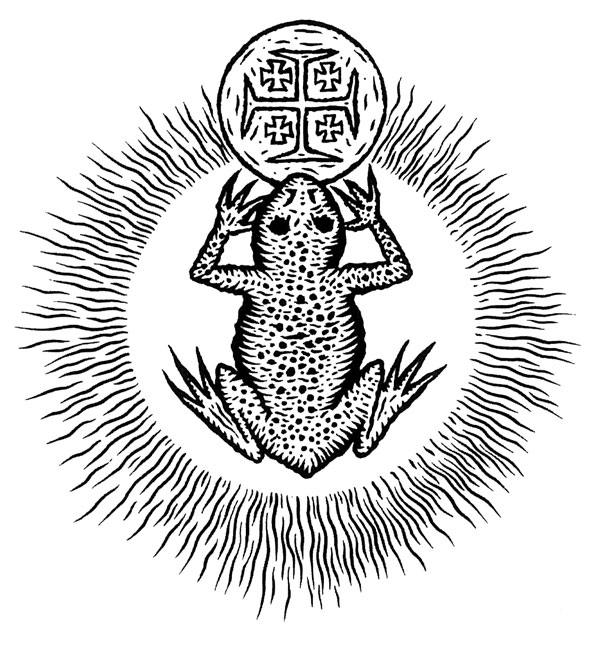

Contrary to what one might expect from the title and the talismanic cover of this book, this volume is not an exploration of the toad rite, or all that much to do with toads at all. Instead, the title marks this out as something of an annotated grimoire, a West Country Black Pullet as it were, collecting magic and charms from that area of England. While much of Gemma Gary’s work presents a system of witchcraft that speaks to a living, breathing, tradition, this is work is more of a documentary, free of much comment or integration into a broader system.

Contrary to what one might expect from the title and the talismanic cover of this book, this volume is not an exploration of the toad rite, or all that much to do with toads at all. Instead, the title marks this out as something of an annotated grimoire, a West Country Black Pullet as it were, collecting magic and charms from that area of England. While much of Gemma Gary’s work presents a system of witchcraft that speaks to a living, breathing, tradition, this is work is more of a documentary, free of much comment or integration into a broader system.

One of the specific focuses of this book is what is referred to as dual faith observance, the way in which the practices of witchcraft and magic were not always, or at all, pagan, and instead were contextualised within the prevailing Judaeo-Christian paradigm of the time. Michael Howard makes mention of this in his introduction, and Gary does likewise in hers. What this means on a practical level is that many of the longer charms included in this work incorporate biblical psalms which might sit somewhat incongruously for people more familiar, and comfortable, with the idea of witchcraft as entirely a continuation or revival of ancient pagan religion.

The Black Toad is divided into three main sections, each dedicated to a different Old Mother: Red-Cap, Green-Cap and Black Cap. The first of these, Old Mother Red-Cap, is a compendium of charms and spells. These spells address relatively common concerns of folk magic, protection and the healing of physical ailments, with a preponderance of methods for dealing with warts, perhaps not quite the scourge now that it evidently once used to be. The charms in the second half of this section incorporate magic squares into their formulae, including familiar ones such as MILON and NASI, suggesting some passing knowledge of The Book of Abramelin or similar texts, while the words of the famous SATOR square are expanded into a longer invocation used to attain anything you desire. All of these charms and spells are presented without comment, and without any referencing or specific provenance, so it is unclear as to whether they come from a single written source, what time they date from, or how widely they were used.

Old Mother Green-Cap, as its name suggests, focuses on matters botanical, beginning with a brief survey of various plants and their magical and medicinal properties; though principally the latter. These are followed by sections on various ways in which specific plants can be used: as infusions of virtue, as protective plant charms, as plant charms for love, for animals, and in a general curative capacity. Here, naturally, if Old Mother Red-Cap’s methods of dealing with those troublesome and persistent warts proved less than efficacious, there are plant-based options available to you using Groundsel or Gooseberry.

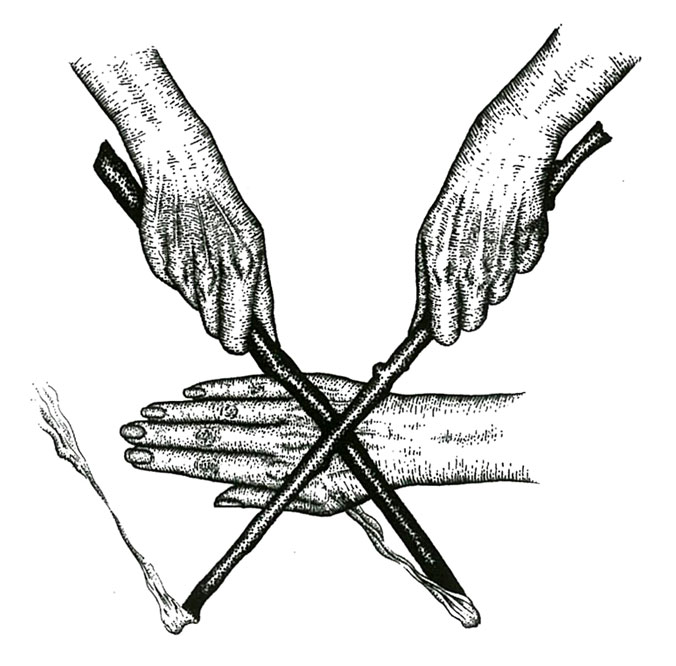

In the final mother, she of the Black-Cap, the focus turns to maleficia, with Gary prefacing the section by referring to the Double Ways practitioners of Cornish and West Country witchcraft, in which one’s status as black or white is entirely dependent on what the client expects of you. This section is, thus, comprised of various spells and formula of opposition and attack. There are spells with a focus on sympathetic magic, using footprints as the focus of attack and control, and the intriguing method called the Ill-Wishing Bag. Old Mother Black-Cap also provides an opportunity to turn to the more darkly-dyed side of the Double Ways, with a discussion of the role in West Country witchcraft of the Old One of Many Names: the Bucca Dhu, Old Nick, the Black God, the Devil. With this is also a brief consideration of the black toad of the book’s title, which is described as having the most inextricable and symbiotic relationship with West Country witchcraft of all the theriomorphous entities of witchlore. Gary makes a distinction between the West Country toad witch and the perhaps more familiar toad doctors, who would cruelly use batrachian body parts in their charms, as well as the equally-lethal initiatory use of the toad in East Anglian practices. Instead the relationship, which appears to act as an overall philosophy for West Country witchcraft, is a symbiotic one, better represented in the image of witch and beloved familiar.

As a whole, The Black Toad is devoid of much in the way of an editorial voice, indeed it lacks much of a distinctive voice at all, seeming to shift tone, manner and vocabulary at times, as if some of the spells have been taken verbatim from their source. Information is presented in a brief, matter of fact manner, and it is only in the final Black-Cap section that a more expansive tone makes a welcomed appearance, allowing for elaboration and analysis. It is here, in the discussion of the Old One with its accompanying paean to toads, that one gets a sense of Gary’s true voice, with the emergence of her writing style that is always a joy to read.

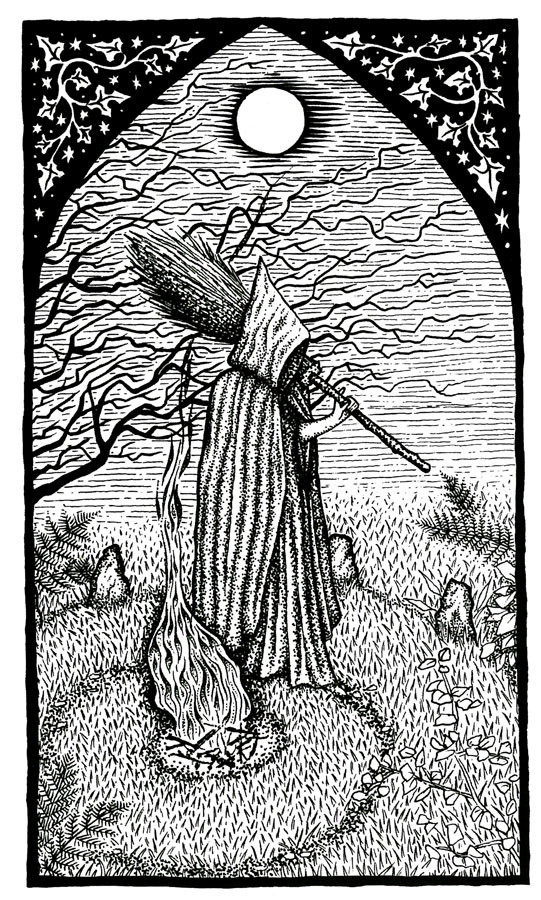

As with all of Gary’s books, The Black Toad is copiously illustrated in her trademark style of line and stipple. These range from beautifully rendered little page fillers, with a surfeit of skulls and other magical accoutrements, to full page, chapter-prefacing illustrations. As ever, these are beautifully rendered and make the perfect visual accompaniment to Gary’s subject matter: suggesting elements both archaic and hands-on, but with an unmistakeably modern touch. In addition to these, there are several pages of photographic plates by Jane Cox, documenting, for the most part, various magical objects, predominantly from the author’s personal collection or the Boscastle Museum of Witchcraft.

Published by Troy Books

Pingback: Linkage: Connection, calls, and moon magick | Spiral Nature Magazine