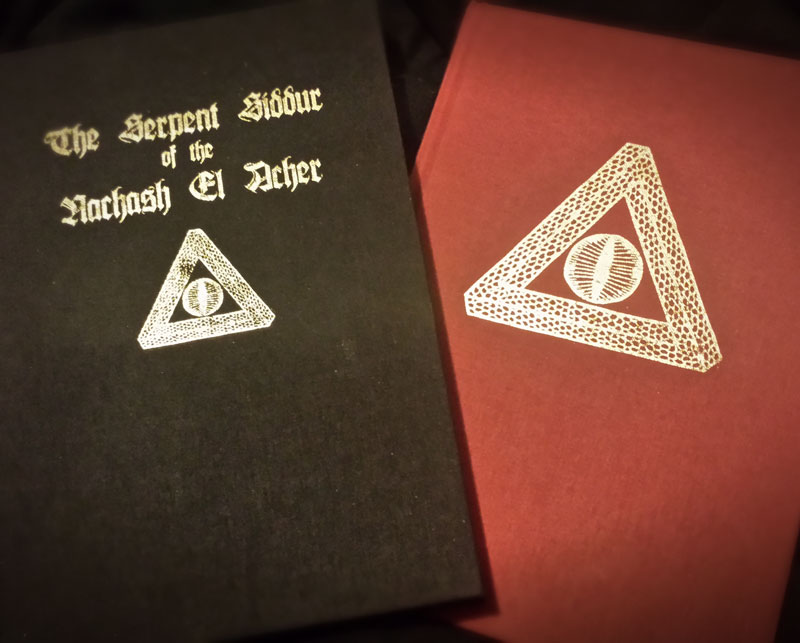

I always find the title of this book from Aeon Sophia Press a little confusing. Is it The Serpent Siddur of the Nachash El Acher, as it appears on the cover, or is it Lyrics of Lilith, Songs of Samael, as it appears on the spine and the internal title pages? If it is both, then which comes first, which is the main title and which is the sub? Either way, this book is a siddur, in that it is largely a collection of prayers and devotional formulas directed to Nachash El Acher, the serpentine god of the Other Side, otherwise known by the portmanteau of Samaelilith.

I always find the title of this book from Aeon Sophia Press a little confusing. Is it The Serpent Siddur of the Nachash El Acher, as it appears on the cover, or is it Lyrics of Lilith, Songs of Samael, as it appears on the spine and the internal title pages? If it is both, then which comes first, which is the main title and which is the sub? Either way, this book is a siddur, in that it is largely a collection of prayers and devotional formulas directed to Nachash El Acher, the serpentine god of the Other Side, otherwise known by the portmanteau of Samaelilith.

Matthew Wightman writes very much from an anti-cosmic perspective and if you’ve read some of the other reviews on this site before, you’ll know that I have something of a disconnect with that most metal and misanthropic of metaphysical mind-sets. My misgivings are by no means assuaged when the opening line of the first chapter bleakly informs us that: “Existence is trauma.” A cheery start, to be sure.

Although Wightman is clearly and admittedly indebted to the Temple of the Black Light and their 218 current, he marks a divergence with their philosophy, talking of a realisation that he had which effectively means that the Temple just aren’t anti-cosmic enough. The crux of the issue is that in the qliphothic sorcery of the Temple of the Black Light, the Qliphoth is seen to be in anti-cosmic opposition to the Sephiroth and everything else on the dayside. Wightman, on the other hand, now sees the Qliphoth as part of a ruse, an agency of disinformation if you will, with the denizens of the Sitra Achra merely reinforcing, by their actions and their nature, a narrative that has been dictated by the Demiurge. Both the dayside and the nightside, these two opposing forces, are therefore, in actuality what makes up the Cosmos, so for Wightman, a true anti-cosmic force needs to be found elsewhere. Instead, Wightman turns his affections to the concept of Ain or Impossibility, seeking a return to the Ayin or Void, and attributing this same desire as the fundamental modus operandi of the Serpent. Wightman describes these ideas as being part of a Current 61, the Current of Ain and the Nachash El Acher, which he describes as even more “anti-cosmic than those that have come before it.” It does comes across a little like misanthropic hipsterism, evoking an image of duelling denizens of some qliphothic Shoreditch questioning each other’s commitment to an obscure band: “I believe in more dissolution into more nothingness than you do.” “Oh yeah, well my rejection of existence is so rejecty that I reject the rejection of existence.” And so forth.

As a disinterested party, these qabbalistic metaphysics can get a bit overwhelming and it’s hard to quiet the inner sceptic who sees it all as pointless speculation about concepts that are just made up anyway. Of course, that’s the nature of any belief system for which there is barely, if any, empirical evidence, but it seems particularly obvious here where so much time is given over to elaborate concepts and conclusions based ultimately on a matter of opinion and a little too much pondering.

This anti-cosmic worldview permeates much of The Serpent Siddur of the Nachash El Acher but the lion share of the book is given over to prayers and rituals, rather than theory. These prayers are recited using several ritual props borrowed from Judaism and Christianity and reoriented to a serpentine focus: a Serpentine Prayer Shawl (made from both linen and wool just to get the Demiurge really miffed that his instructions in Deuteronomy are being flouted; talk about sticking it to the man), Serpentine Phylacteries (with the original Judaic scrolls burnt and the ashes placed back in the tefillin) and a Serpentine Rosary. The prayers themselves are very long with the evening meditation running to sixteen pages, while the Serpent Sermon is comparatively short at only nine pages. On the blessedly shorter side of things are a Hymn to Qayin and songs for each day of the week, as well as a listing of thirteen principles, and prayers for prosperity and for the close of service. There are also meditations for before bed, for morning, and for afternoon, as well as prayers for before and after meals, and a series of prayers and invocations for the spirits of the twelve Qliphoth; although, given the earlier dismissal of the nightside of the Tree of Life as part of the Demiurgic problem, it’s not really explained what they’re doing there.

There’s a certain repetition of themes across this liturgy with much cursing of the Demiurge, praising of the Serpent and a total dissing of the Clayborn; boo, really hate those guys. The negativity of it all gets a bit much for my tender sensibilities and the constant blasphemy against the Demiurge and remarks about what a big meanie he is wears thin very early on. Similarly, the repeated mutterings about the Clayborn ends up making you feel like you’re on an Alex Jones website with people complaining about the Sheeple that just won’t wake up.

The second half of The Serpent Siddur of the Nachash El Acher is, at least in the regular version that I have, bound as a separate book and acts as expanded appendix to the hymnal of the first half. This is a collection of essays, some previously published, as well as an interview with Wightman conducted by Aeon Sophia Press, in which he is able to elaborate more fully on some of the cosmological and metaphysical concepts that are considered only briefly in the first volume. The essays are presented, as far I can tell, as they were originally printed and have not been updated and edited for this collection; something they may have benefited from. For example, in the first two essays, written in 2012 and 2013, Wightman refers to what he calls the Ain Sof Choshek by the name of Tiamat, which stands out somewhat incongruously within a sea of qabbalistic Hebrew, but in a later essay (and in the first volume of the siddur) he adopts the appropriately Hebrew name Tanninim as the result of a discussion with the Temple of the Black Light. What this lack of retroactive editing means is that Wightman allows you to effectively track his changes, revealing the evolution of his thought process. Jesus, for example, goes from being someone to be completely despised in an earlier essay to being seen within a more sanguine worldview in which he is a time bomb double agent whose sacrifice is used to disrupt the Demiurge and their plans.

Across both volumes, Wightman writes very well, presumably benefiting from his theological studies at Yale. Having edited a previous Ixaxaar title, he obviously has a thorough grasp of his subject. The content is largely proofed well and the only time things really go awry is when biblical turns of phrase get the better of Wightman and yoke is, one assumes, mistakenly rendered as yolk, with the phrase “the yolk of the Demiurge was around my neck” bringing to mind some rather sticky cosmological culinary accident.

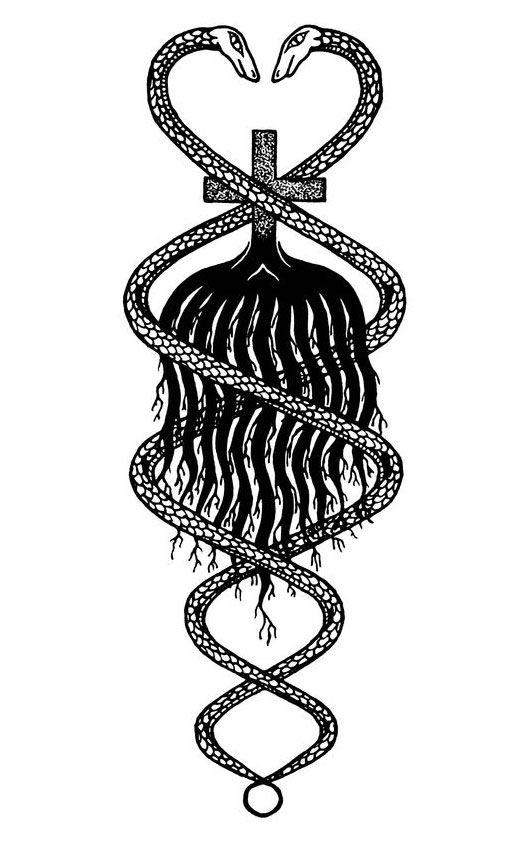

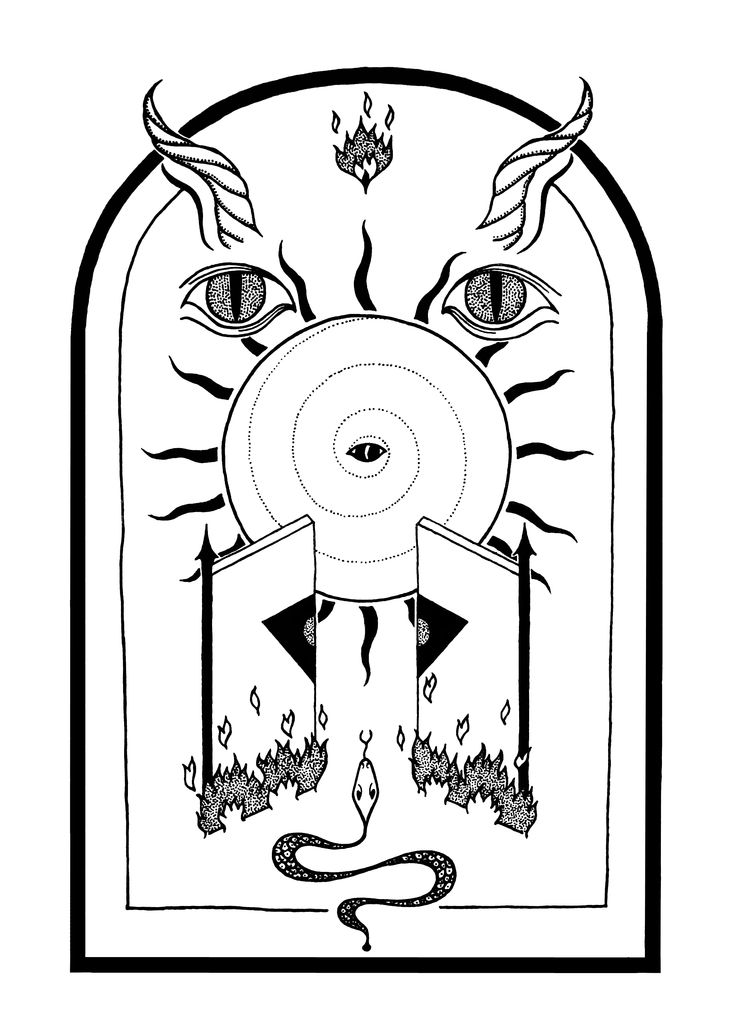

Both volumes of The Serpent Siddur of the Nachash El Acher feature occasional full page images by Patrick Larabee in his trademark, slightly naïve style. The type is set cleanly throughout, with chapters beginning with dropcaps in the blackletter Killigrew font that is something of an Aeon Sophia Press trademark. Chapter titles, meanwhile, are rendered as small caps in de rigueur Trajan Pro. The two volumes are bound in cloth, black for the first volume and red for the second, with the title rendered in gold foil lettering on the front of the first volume, and a sigil based on a Penrose triangle on the covers of both. Part one has the Lyrics of Lilith, Songs of Samael title running along its spine, but part two doesn’t have anything, making it infuriatingly anonymous when sitting in a bookshelf. It seems a missed opportunity that an attempt wasn’t made to connect the two volumes together, maybe with some treatment that could spread across both spines whilst still working when viewed in isolation. This regular version is sold-out from the publisher but a deluxe leather bound edition, limited to 50 copies, is, at the time of writing, still available.

For anyone who resonates with this kind of blasphemous, transgressive anti-cosmic Satanism, this book will be a valuable addition to their library. For others, it may mine those veins too frequently, and the negative anti-existence talk could begin to grate. While it lacks the ritual rigour and internal complexity/consistency of N.A.A. 218’s similar writings published by Ixaxaar, it does have an enthusiasm that may appeal to some.

Published by Aeon Sophia Press.

Perfect Liber