Ármann Jakobsson is Professor of Medieval Icelandic Literature at Háskóli Íslands/the University of Iceland and has been, as an oft-repeated bio tells it, a postman, a high school teacher, a journalist and critic, a reality TV star and a political activist. Trolls loom large in Ármann’s work, with the 2015/2016 writing of this book coming as the result of eight years working with the subject. It is the product of a research project, Encounters with the Paranormal, which included collaborations with Ásdís Egilsdóttir, Torfi H. Tulinius, Terry Gunnell and Stephen Mitchell, as well as eight doctoral students, and three masters students who wrote their theses within the parametres of the project.

Ármann Jakobsson is Professor of Medieval Icelandic Literature at Háskóli Íslands/the University of Iceland and has been, as an oft-repeated bio tells it, a postman, a high school teacher, a journalist and critic, a reality TV star and a political activist. Trolls loom large in Ármann’s work, with the 2015/2016 writing of this book coming as the result of eight years working with the subject. It is the product of a research project, Encounters with the Paranormal, which included collaborations with Ásdís Egilsdóttir, Torfi H. Tulinius, Terry Gunnell and Stephen Mitchell, as well as eight doctoral students, and three masters students who wrote their theses within the parametres of the project.

Ármann makes it clear from the start that the understanding of the troll, like the troll itself, is a shifting and intangible one – something intrinsic to the troll as a figure of ambiguity and otherness, whose only definable and immutable characteristic is that, due to their eldritch nature, they are to be feared. This resistance to definition, an opposition to any particularly constricting taxonomy, comes from the fact that trolls appear across the centuries in a multiplicity of forms: as ghosts or spirits, as supernatural but corporeal creatures (a categorisation that in itself can be broken down into still further categories), and as nominally human practitioners of sorcery. It is as if, as Ármann pithily notes, the more difficult it becomes to name or classify a monster, the greater the power it wields.

Whilst Ármann draws on Örvar-Odds saga and other sagas of the Icelanders for his initial discussion of trollish ambiguity, for his first thorough literature review he turns to the little known Bergbúa þáttr, whose singular tale tells of an encounter in a cave, sometime after the kristnitaka, between two men and the barely defined, forever ambiguous, bergbúa of the title. Although low on the usage of the specific word ‘troll,’ this story provides a showcase of all the themes Ármann has already identified: liminality, the unheimlich and of boundaries and intersections between worlds, be they human and the paranormal, a Christian present and a heathen past, and at its most obvious and symbolic level, the cave’s interior and exterior.

This idea of troll space is explored further in subsequent chapters, as is the idea of trollspeak, with Ármann citing one example in which the mundanity of the speaking of trolls (not the expected grunts or howls) exacerbates their otherness, upending expectations, and with it, the world itself. Speech and language does figure largely throughout this book, and Ármann builds on his original discussion of the vagaries of the word ‘troll’ with a return to matters epistemological and a meditation of the vocabulary of the paranormal and its intersection with the occult. This is an area fraught with difficulty, and therefore ripe for analysis, because as Ármann notes, the essential nature of the occult is to remain hidden (a quality implicit in the very name), and therefore ambiguous and subject to doubt and uncertainty.

These explorations of language, and of the ambiguity of the figures it tries to define and make sense of, highlights that The Troll Inside You isn’t a study of trolls and their studiously cited source texts; for that there’s John Lindow’s concise Trolls: An Unnatural History, as well as previous writing by Ármann. Instead, the troll is effectively used as a liminal gatekeeper, with its uncanny characteristics and resistance to definition providing a lens through which broader musings on perception and otherness in the Medieval North can be discussed.

As always, Ármann writes in an engaging and enjoyable style, completely immersed in the language of academia’s modalities, but without overuse of that particular lexicon. While there’s a place for the convoluted styles of a Morton or Butler, it’s not here, and it doesn’t seem to be part of Ármann’s personality. Instead, he’s more interested in connecting with the reader with a clear, informed voice that is authoritative but by no means fustian. He also shows an arch sense of humour, such as an abrupt fourth-wall-breaking coda which he subtitles archaically as “Coda: In Which the Audience is Unexpectedly Addressed,” producing a truly laugh-out-loud moment.

The structure of The Troll Inside You assists its readability with often brisk (though annoyingly unnumbered) chapters that act as perfectly digestible little chunks of trollish goodness. Similarly, from a technical perspective, the type is set matter-of-factly and competently in an atypical slab serif that ensures readability but has a modern touch.

The end to The Troll Inside You sneaks up quickly on you, as the pure content finishes abruptly and early at the 163rd of its total 240 pages, with the rest of the book consisting of endnotes and an index. As the page count evinces, these endnotes are extensive and feature considerable elaboration, rather than simple citations or qualifications. Some run to half a page, with a small point size at that, so for those who interest is piqued, there’s a lot of adjunct material to dive into, and a lot of flicking to the end section as you read.

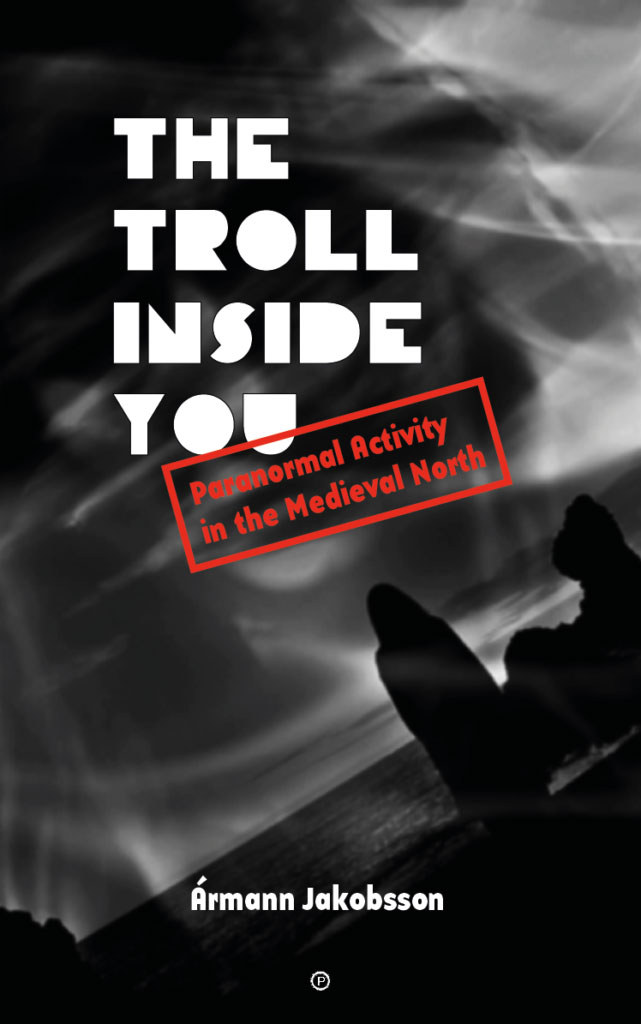

In their short seven years, Punctum Books have amassed an amazing collection of cover art, some full of whimsy, some with great contemporary design, and some that are just straight-up beautiful (yes, I’m looking at you, Visceral: Essays on Illness Not as Metaphor). I’m not sure where the cover of The Troll Inside You sits in relation to those. With the subtitle rendered like a stamp, there was obviously an attempt to play on a more contemporary idea of paranormal investigations (if we can called the X-Files and its aesthetic antecedents contemporary), rather than something distinctly medieval Scandinavian or academic. This, in turn, sits rather incongruously with the main title which is rendered in a geometric face with the counters filled in; a questionable typographic trend whose peak was some ten years hence. It’s all very aberrant, and dissociative, which, mayhaps, allows one to go “Aha, that’s what we were going for all along.”

Published by Punctum Books.

Published by Punctum Books.