Published by Dead Letter Office, Punctum Books’ imprint for “work that either has gone “nowhere” or will likely go nowhere,” this is a brief work from Alexander Doty and Patricia Clare Ingham, published posthumously following Doty’s death in 2012. The two first collaborated on an essay that, like the ones compiled here, considered the intersection between an occult work of celluloid fiction and its real world, pre-modern textual history: Val Tournier’s Cat People. In the case of the work reviewed here, Doty introduced Ingham to Benjamin Christensen’s 1922 film Häxan at a class they team-taught in 2001, and she, in turn, told him to read Malleus Maleficarum. Life intervened until the two returned to the theme in 2008, finding the impetus to begin work on this book at last, before reconvening in 2012 with a short text that was submitted to Punctum Books. Unfortunately, Doty died in August of that year, two weeks before they received recommendations for revisions and approval to publish from Punctum.

Published by Dead Letter Office, Punctum Books’ imprint for “work that either has gone “nowhere” or will likely go nowhere,” this is a brief work from Alexander Doty and Patricia Clare Ingham, published posthumously following Doty’s death in 2012. The two first collaborated on an essay that, like the ones compiled here, considered the intersection between an occult work of celluloid fiction and its real world, pre-modern textual history: Val Tournier’s Cat People. In the case of the work reviewed here, Doty introduced Ingham to Benjamin Christensen’s 1922 film Häxan at a class they team-taught in 2001, and she, in turn, told him to read Malleus Maleficarum. Life intervened until the two returned to the theme in 2008, finding the impetus to begin work on this book at last, before reconvening in 2012 with a short text that was submitted to Punctum Books. Unfortunately, Doty died in August of that year, two weeks before they received recommendations for revisions and approval to publish from Punctum.

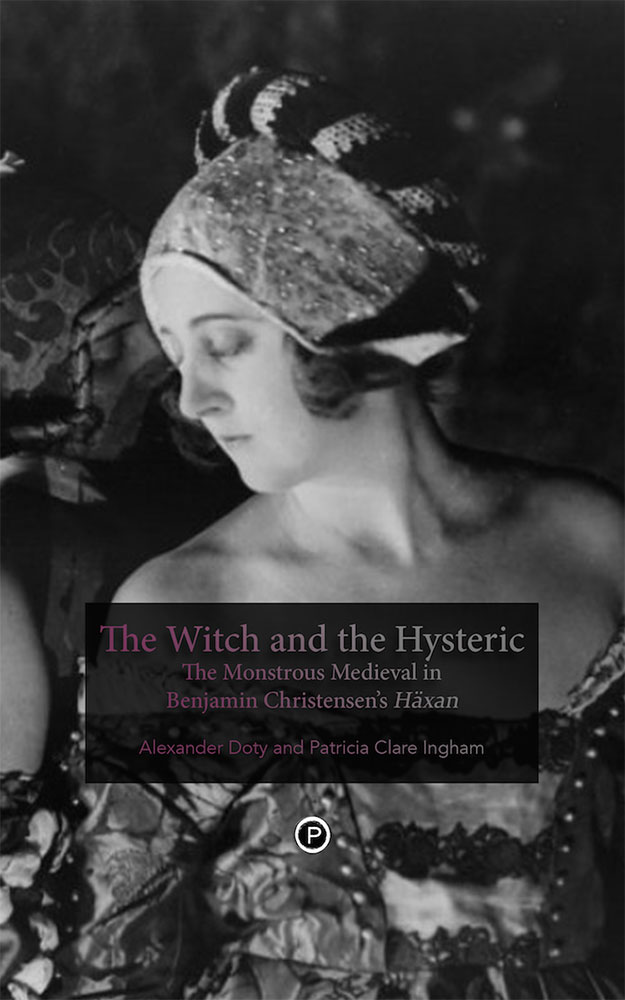

Despite the enduring popularity of Häxan, with the film having several versions released over the years (including an edit with narration by William Burroughs) and multiple scores composed for it, little has been written critically about it. Its influence on other film-makers has been noted but less made of its uncanny style mixing documentary and fantasy, both in its content and structure, which combines fictional episodes, illustrated lectures, and dreamscapes, all divided into seven ‘chapters.’ With medieval scholarship’s love of the monstrous this is somewhat surprising but Doty and Ingham redress this imbalance, arguing for Christensen’s Malleus Maleficarum-inspired witch as a monster herself, whose placement within an ill-defined middle ages signals both a category crisis and a temporal paradox.

Doty and Ingham see the untimely temporality in Christensen’s depiction of the witch as a recapitulation of the two early modern visions of witchcraft, one being that of Heinrich Kramer in the aforementioned Malleus Maleficarum, whilst the other is that of Johann Weyer in De praestigitis daemonum. Both men’s take on witchcraft effectively centred around whether to believe women, with the Catholic Kramer arguing for the literal nature of what accused witches claimed to have experienced (bringing with it affirmation of a belief in the Christian supernatural world), whereas the Lutheran Weyer was quite willing to see the very same as the result of delusions, giving the reports the equivalent veracity of the confessions of melancholics and the mentally incompetent. Ironically, the rationalist views of Weyer (who is touted by Gregory Zillboorg as a father to modern psychiatry) is the more disempowering of the two for the women in question, rendering them victims of their delusions and phantasms (rather than complicit wielders of dark glamour), and linking them, by implicit association, with mental illness and depression.

But we digress, suffice to say that Doty and Ingham use the debt that Christensen’s witch owes to Kramer and Weyer to discuss both men’s approach to the matter in hand, with little immediate reference back to Häxan itself for now. This makes the second chapter an intriguing and engaging summary of the texts of both men and their attendant worldviews, analysing their motivations and resulting implications, as their respective opinions track the greater early modern theological debate on maleficia. In the third chapter, Doty and Ingham continue to consider this influence, noting its effect of psychiatry and in particular the work of Freud and his conception of the hysteric, and also on other matters of epistemology. They refer to Kathleen Biddick’s assessment that the Malleus Maleficarum played a key role in epistemological methods of eyewitness reports and ethnography, with the figure of the Devil creating for both Inquisitors and historians a lens through which the accused women could be viewed, making their diabolical practice visible and thus evidentiary.

These considerations converge with Christensen’s Häxan in the book’s fourth chapter, Witch, Past and Future: The Politics of Retroactive Diagnosis, where Doty and Ingham highlight examples of this dichotomy betwixt the religious and scientific views of the witch. In particular they mention the scene in which a depiction of female witches is contrasted with one in which superstition-driven accusations of witchcraft are made against two male medical students, whose righteously scientific but still felonious grave robbing is placed in opposition to the irrationality of religion. In a similar vein, Christensen transitions from the close-up image of a woman’s back being pricked by Inquisitors in order to find areas of insensitivity (a tell-tale sign of guilt), to one of the same procedure being performed in a contemporary doctor’s office, ultimately diagnosing the patient with hysteria. In an interstitial, Christensen addresses the woman in question, describing her as a “poor little hysterical witch” who in the Middle Ages was in conflict with the church while now it is with the law.

Doty and Ingham note that for all his interest in technological innovation in film, Christensen appears preoccupied with historical repetition, with his analogies between the female medieval witch and the modern hysteric denoting a continuity at the centre of which is the figure of the abnormal woman. While the world around her changes, for her, the journey from demonic possession to mental illness has affected her little, and she remains monstrous and abject, perpetually in need of rescue and rehabilitation.

As its title and length of a mere 60 or so pages indicates, there is not much else considered here than Christiansen’s core conflation of the medieval witch with the contemporary hysteric, along with its theological and psychiatric underpinnings. Doty and Ingham write with an inquisitor-like focus, narrowing their gaze on this particular area of witchcraft records and analysis, with an engaging manner that draws from both areas with equal ease and erudition.

Published by Dead Letter Office/Punctum Books