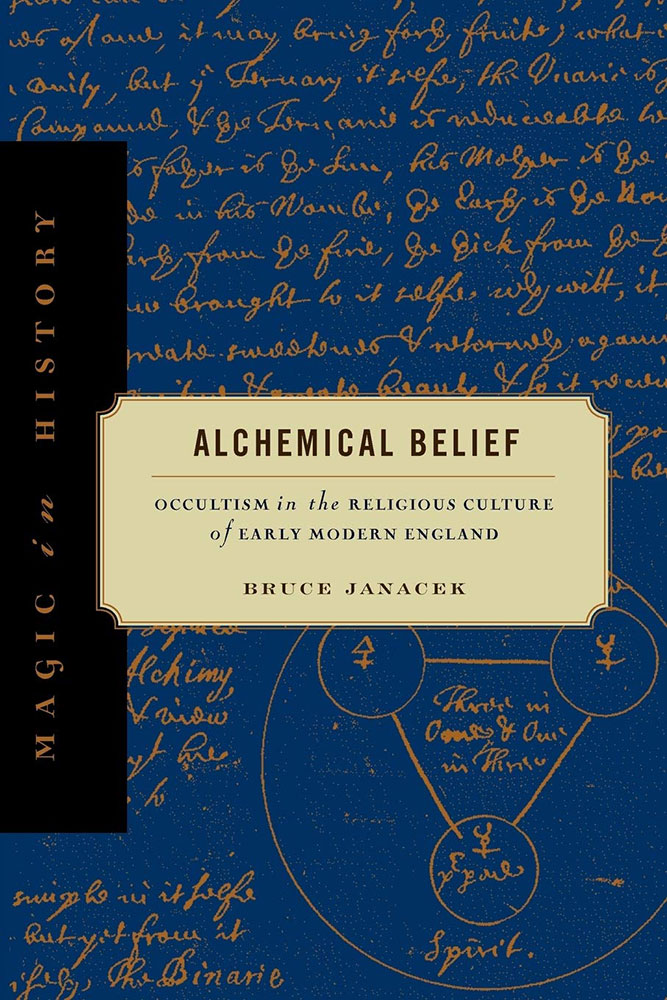

Like Bruce Janacek’s recently reviewed Alchemical Belief: Occultism in the Religious Culture of Early Modern England, this book is concerned with how alchemy was perceived in Early Modern England, with the focus here being on literary works. Rather than simply providing a survey of specifically alchemical literature from alchemists and their advocates, Eoin Bentick casts a wider net to provide more fluid understandings of the art in that period, exploring how it was conceptualised by adept and sceptic alike, and how its obfuscated language was interpreted by those who didn’t know their alembic from their athanor. In so doing, Bentick endeavours to answer the question as to why the difficult writing and language of alchemy held appeal for so many.

Like Bruce Janacek’s recently reviewed Alchemical Belief: Occultism in the Religious Culture of Early Modern England, this book is concerned with how alchemy was perceived in Early Modern England, with the focus here being on literary works. Rather than simply providing a survey of specifically alchemical literature from alchemists and their advocates, Eoin Bentick casts a wider net to provide more fluid understandings of the art in that period, exploring how it was conceptualised by adept and sceptic alike, and how its obfuscated language was interpreted by those who didn’t know their alembic from their athanor. In so doing, Bentick endeavours to answer the question as to why the difficult writing and language of alchemy held appeal for so many.

Literatures of Alchemy in Medieval and Early Modern England has its content divided into two sections, the first considering how alchemical obtuseness was dealt with in medieval poetry and academia, as well as the wider culture. The second turns to the language of alchemy itself and narrows the view in particular to how it was read and understood by those novitiates beginning their alchemical journey. Bentick opens with an introduction, but this is no mere formality and instead gives a thorough history of alchemy, beginning in Egypt with Zosimos of Panopolis, marking its growth in the Arab world, and then its expansion into Europe where it was assimilated into the canon of Latin scientific literature and even incorporated into Christian cosmology. Concise yet detailed, this makes for a valuable primer, even for those who might be familiar with alchemical history, allowing the background of alchemy and its procedures to be covered off before getting to the grist of this book: writings about the thing, not the thing itself..

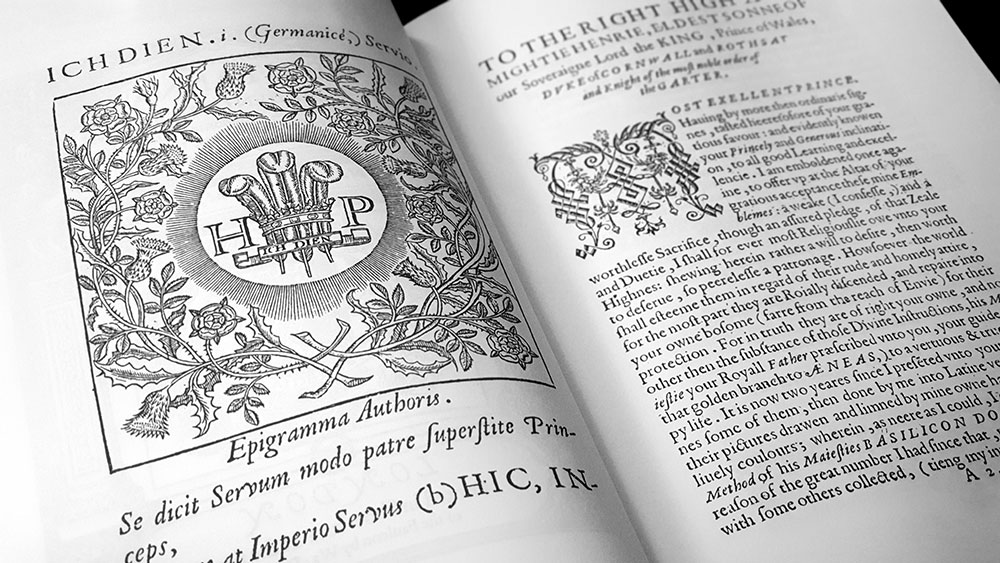

The first chapter bears the intriguing title Ignotum Per Ignocius: Literatures of Alchemical Impotence, the choice of which becomes clear when the topic is depictions of alchemists as fools or dupes. Satirisation was the name of the game in the medieval and early modern periods, with alchemists represented in literature as either tricksters or the tricked. Bentick gives a variety of examples from Ben Johnson, Dante and Petrarch, but the largest analysis is of the Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in which the yeoman tells two stories, each about a different canon, both of whom are deceitful alchemists. The canon whom the yeoman is indentured to appears to be inept, despite his claims of great skill, while the second canon is a charlatan who tricks a priest into buying a recipe with the claim that it can turn things into silver. As S. Foster Damon argued 100 years ago in his article Chaucer and Alchemy, Chaucer may have attacked charlatan alchemists because they were becoming a public menace, but he appears to have also surreptitiously included information so that genuine alchemists would recognise him as one of their own; which they did. Indeed, Chaucer provides something of a through line within this book, being a friend of John Gower who is discussed in the second chapter, while a century later, the poet and alchemist Thomas Norton satirised the alchemical bona fides that Chaucer had been given.

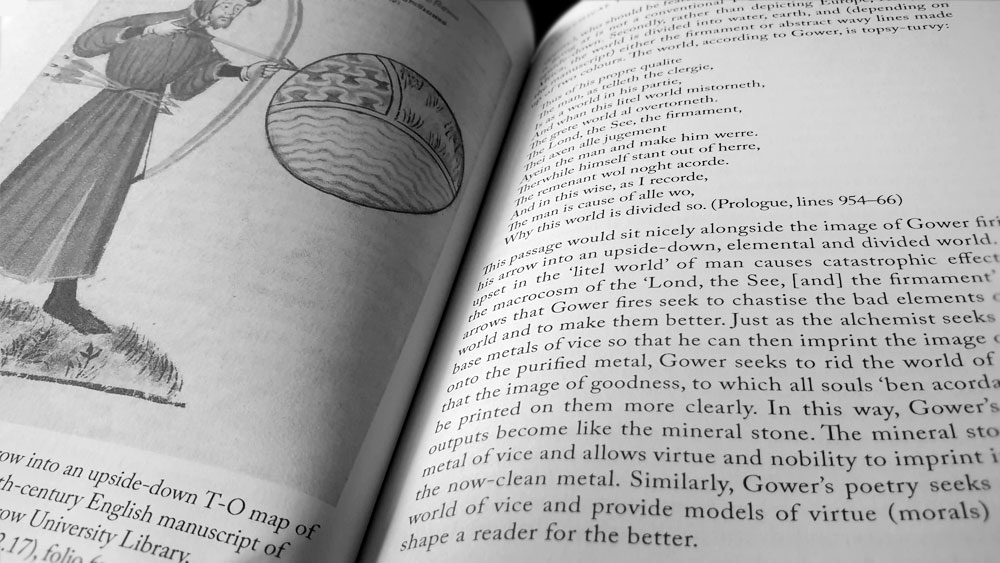

Questions of morality and character arise again in the second chapter, Alchemical Theories of Social Reform, in which Bentick surveys the use of alchemy as a metaphor or analogy of the reinvigoration of a fallen present. The obvious exemplar of this is what Bentick refers to as the Holistic Alchemy of Roger Bacon, with the Doctor Mirabilis seeing alchemy as a force for social evolution, though perhaps not in the most altruistic of manners. Based on a unique misreading of the pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum Secretorum (a work that presents itself as messages given by Aristotle to Alexander during the conquest of Achaemenid Persia), Bacon believed that it was through the alchemical principles taught by Aristotle that Alexander was able to conquer the known world. For Bacon, people could be changed by the manipulation of the elements, making it possible for a skilled alchemist to transmute an entire population on the macrocosmic level just as they would the microcosmic elements in a laboratory. As unethical as this sounds, Bentick notes that this core idea would influence others who saw alchemy as capable of social improvement, such as the 14th century poet John Gower and the 15th century poet and alchemist, Thomas Norton. While Gower followed Bacon’s model of a moral universal improvement, Norton focussed on the idea of a redemptive Alchemical King whose changes would be more overtly political, one who would Antiquos mores mutabit in meliores (‘change old ways into better.’).

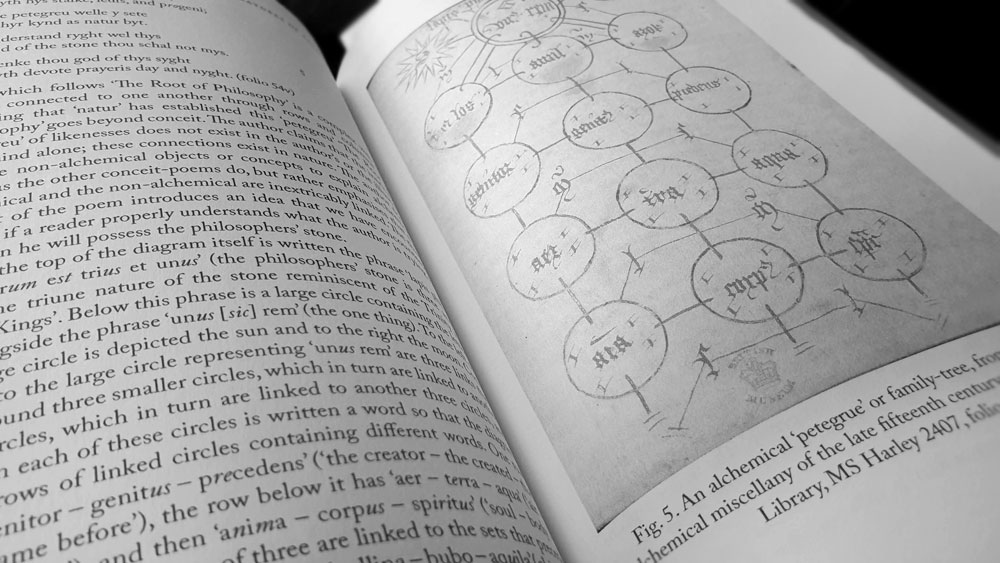

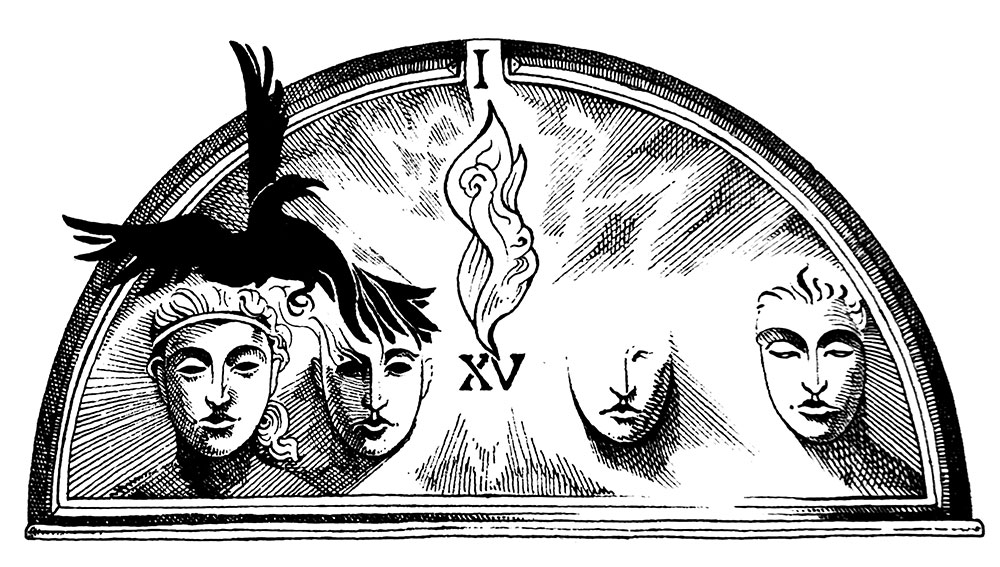

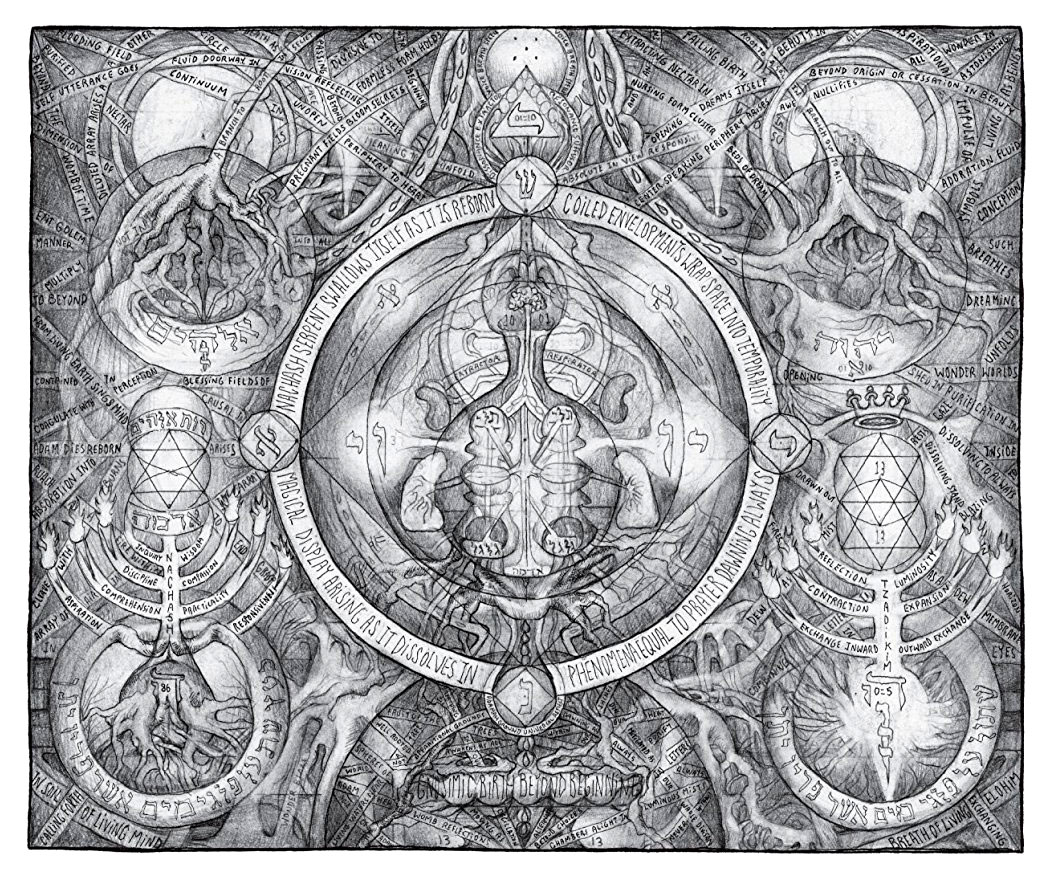

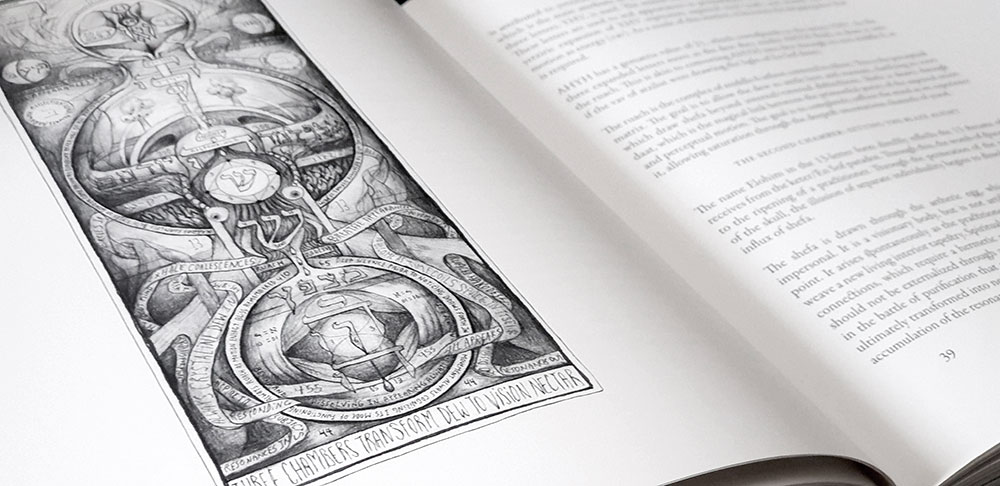

For his third chapter, British Library, MS Harley 2407, Bentick turns to the manuscript of the title and considers its compilation of alchemy-related poems. The MS consists of six booklets, mostly written by two fifteenth-century scribes, with over twenty people contributing to an accretion of notes in the margins and spaces from the fifteenth to eighteenth century; including the recognisable hands of John Dee and Elias Ashmole. There are nine Middle English poems in the manuscript, making it indicative of the veritable boom in English alchemical verse in the fifteenth century and onwards; contrasting with previous centuries in which Latin prose had dominated as the lingua alchemica, and with only a fraction of that being presented in verse. The clutch from this manuscript are categorised by Bentick as recipe poems, gnomic poems, theoretical poems, and conceit poems, and he provides an analysis of each one under those groupings.

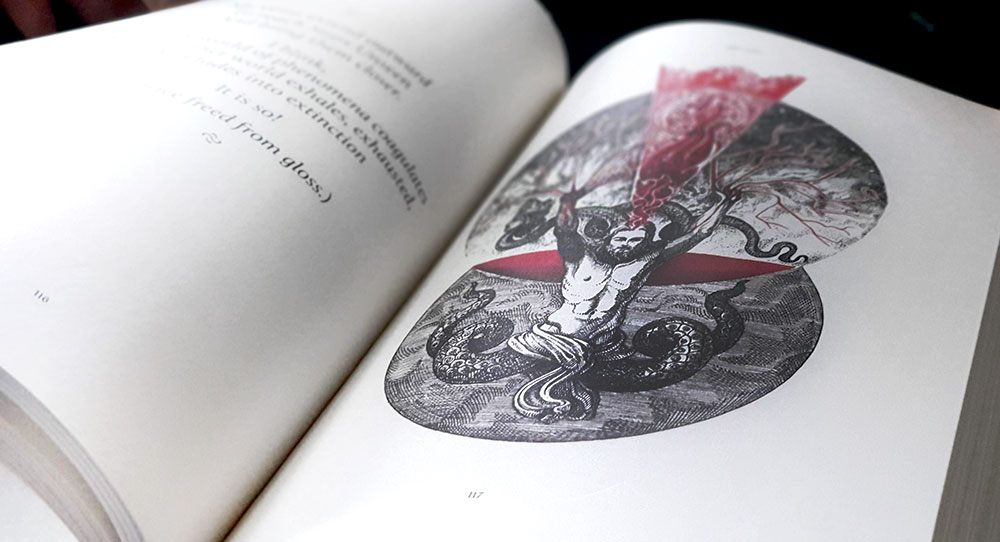

Bentick’s fourth and final chapter, Alchemical Hermeneutics, opens with a discussion on how alchemists, with their reverence for the inerrancy of the past, reacted when coming across alchemical information that was contrary to either their training or experience. The assimilation of such potentially false knowledge required interpretation, rather than dismissal, using an Augustinian system of hermeneutics, in which everything, be it text or the physical universe, was to be interpreted in order to discovered the divine truth buried within it. This speaks to Bentick’s core theme here, that the literature of alchemy, be it by novices, sceptics or adepts, helped to perpetuate the allure of alchemy. Even when someone like Chaucer uses the Canon’s Yeoman Canon as a vehicle to depict alchemists as fools or mountebanks, such presentations encouraged readers to seek out the truths that must surely lie behind the façade. Furthermore, the rich symbolism of alchemy ensured its own perpetuity, with its lexicon gifting writers such as Shakespeare and Sidney with ready images of amelioration and mystery. These writers, then, maintained the allure of the arte, adding to its inherent sense of wonder with their alchemical use of language to create even more wonder.

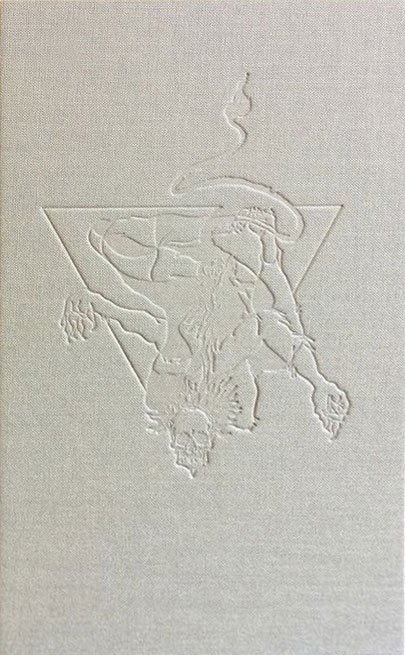

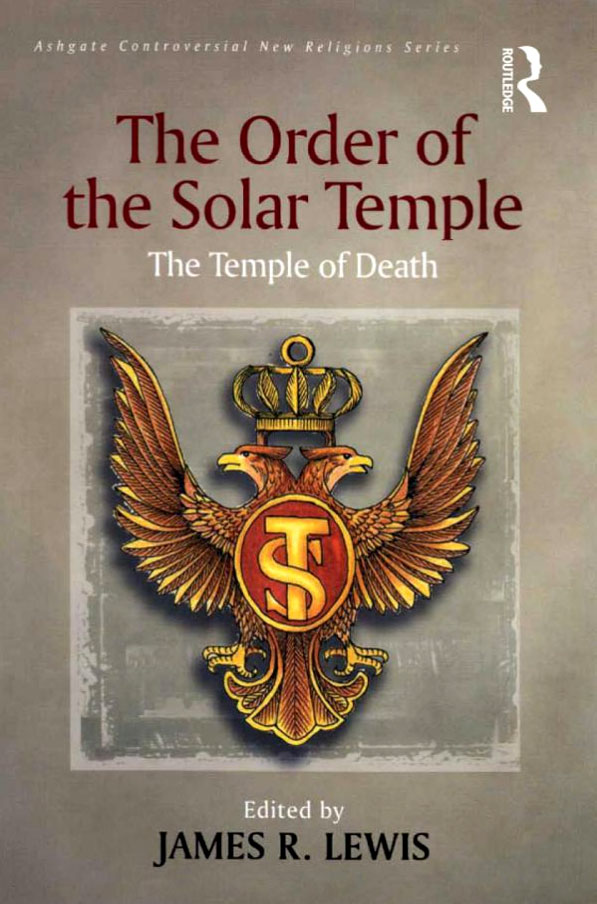

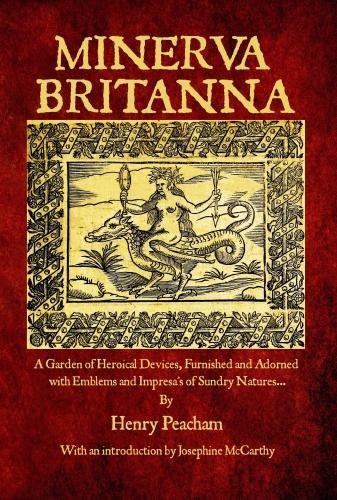

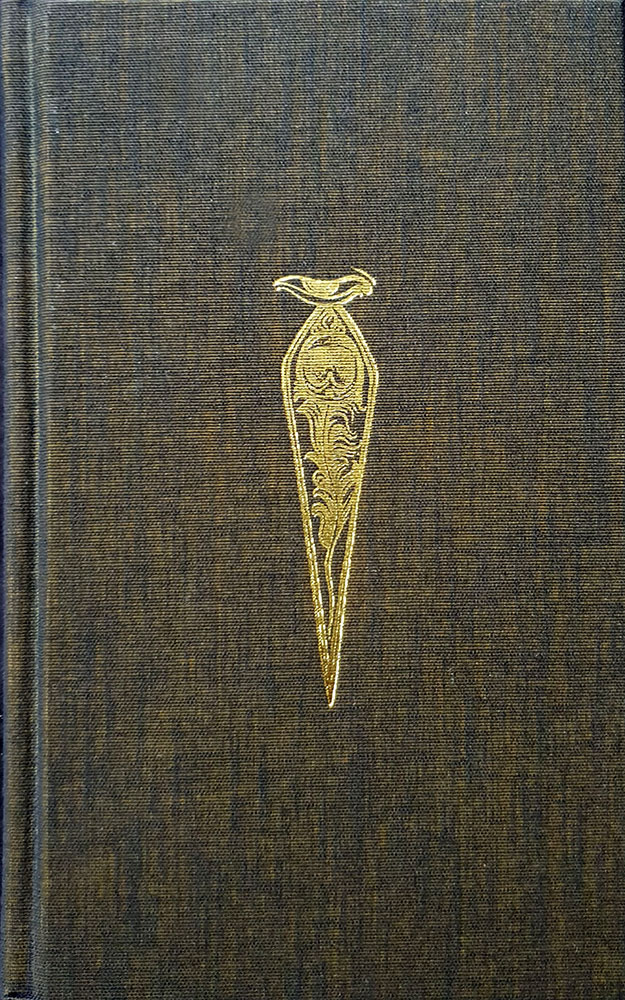

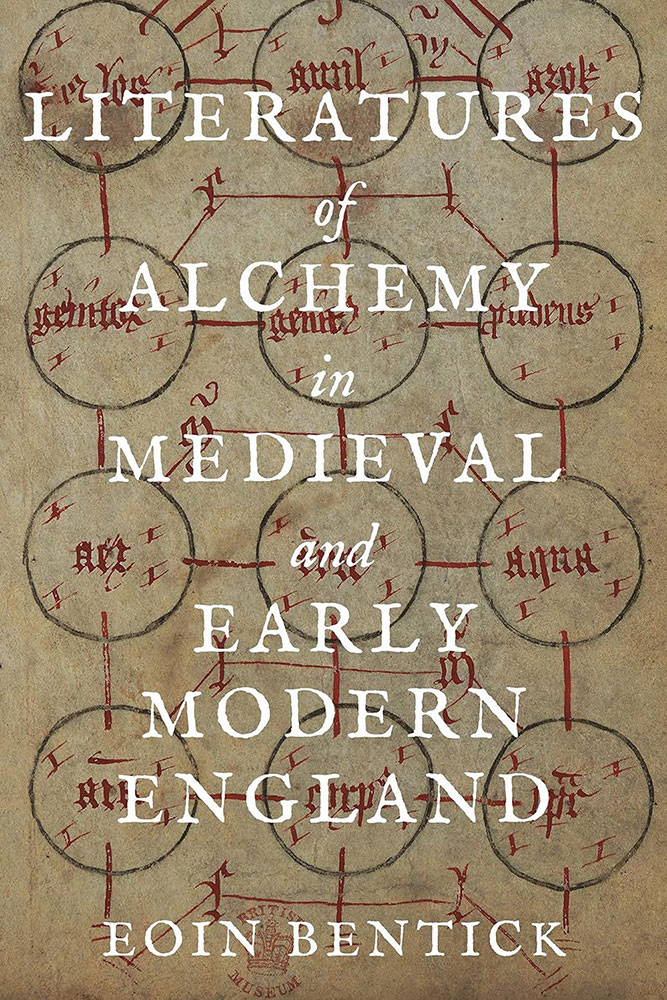

Despite its four chapter length, Literatures of Alchemy in Medieval and Early Modern England feels like it crams a lot into its sub-200 pages. Bentick writes with an assured style, the general thesis being threaded throughout with no sense of wandering off into tangents or becoming mired in irrelevancies. The book is presented by D.S. Brewer as a hardback with a cover design by Hannah Gaskamp that incorporates an alchemical petegrue from MS Harley 2407. In at least this review copy, the pages are printed on an unpleasant acid-free paper by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, leaving a distracting film on one’s fingers with every page turn. In addition, the cover image is sloppily misaligned, drifting off centre so that the petegrue image touches the right edge of the book resulting in a vast empty space being left on the cover’s opposite edge; with the title and printer’s mark on the spine being similarly misaligned. It is not clear whether this slipshod production is true for all copies, or if we just got unlucky.

Published by D.S. Brewer