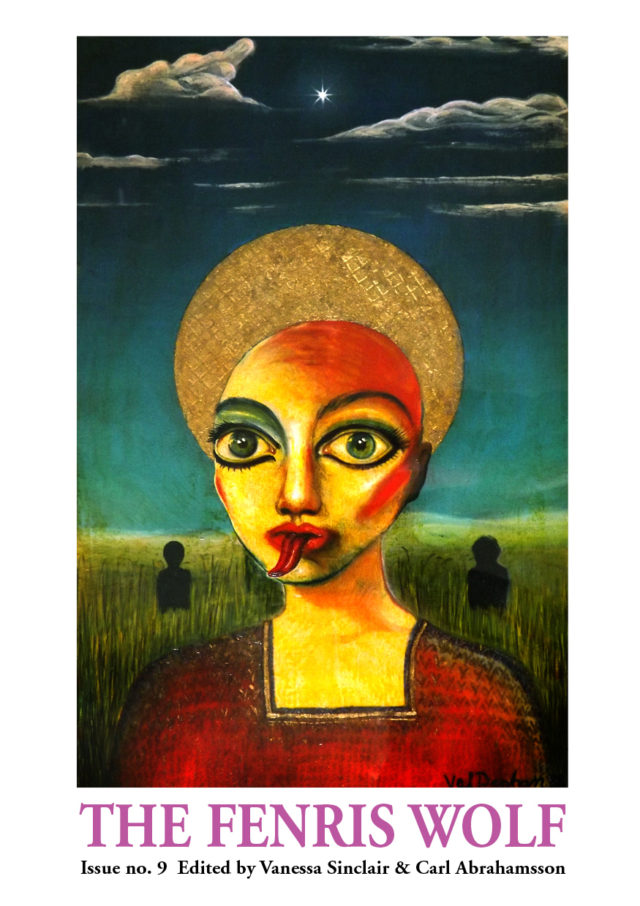

Adorned with stunning, numinous cover art by Val Denham, this is the latest issue of Carl Abrahamsson’s irregularly published esoteric journal and contains material from the 2016 Psychoanalysis, Art & the Occult conference held at the Candid Arts Centre in London. The Fenris Wolf has come a long way from its first issues, as evidenced by a much-loved copy of the third volume from 1993 in the shelves at Scriptus Recensera: its blue perfect-bound spine now sun-faded to a yellowy grey, pages printed with somewhat erratic toner integrity, and images reproduced with very noticeable halftone dots, as was the style of the time.

Adorned with stunning, numinous cover art by Val Denham, this is the latest issue of Carl Abrahamsson’s irregularly published esoteric journal and contains material from the 2016 Psychoanalysis, Art & the Occult conference held at the Candid Arts Centre in London. The Fenris Wolf has come a long way from its first issues, as evidenced by a much-loved copy of the third volume from 1993 in the shelves at Scriptus Recensera: its blue perfect-bound spine now sun-faded to a yellowy grey, pages printed with somewhat erratic toner integrity, and images reproduced with very noticeable halftone dots, as was the style of the time.

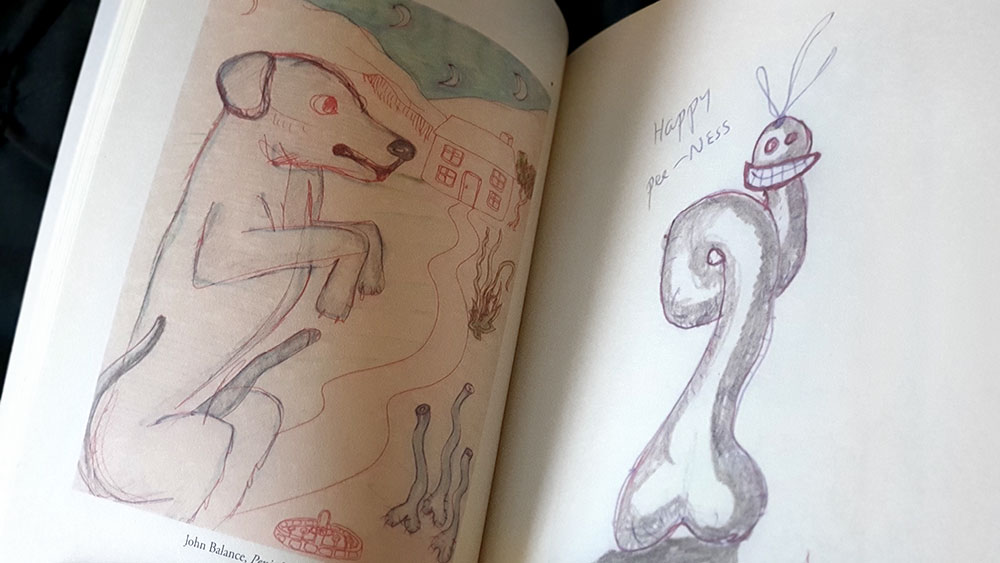

As one would expect given the title of the conference, this issue of The Fenris Wolf has a particular focus on the intersection between psychoanalysis and the occult, with art being often the child thereof. Visual artist and writer, Katelan Foisy, kicks things off with an invocation to the spirits and history of the host city, documenting everything in its history, starting with the Roman founding of Londinium, although ending abruptly in the 1960s, as if anything that happened after Swinging London didn’t amount to much. The first essay, Art as Alchemy, proper brings art to the fore with folk musician Sharron Kraus discussing the cliché of the tortured artist, and questioning whether there’s any truth to that conceit. One such alchemical artist is John Balance of Coil, who is considered here by Graham Duff, not for his musical works but rather his considerably lesser known paintings and drawings. This is an affectionate and generous survey of Balance’s, how do you say, naïve oeuvre, with Duff importing a lot of intent and meaning to what in many cases are doodles of, well, doodles.

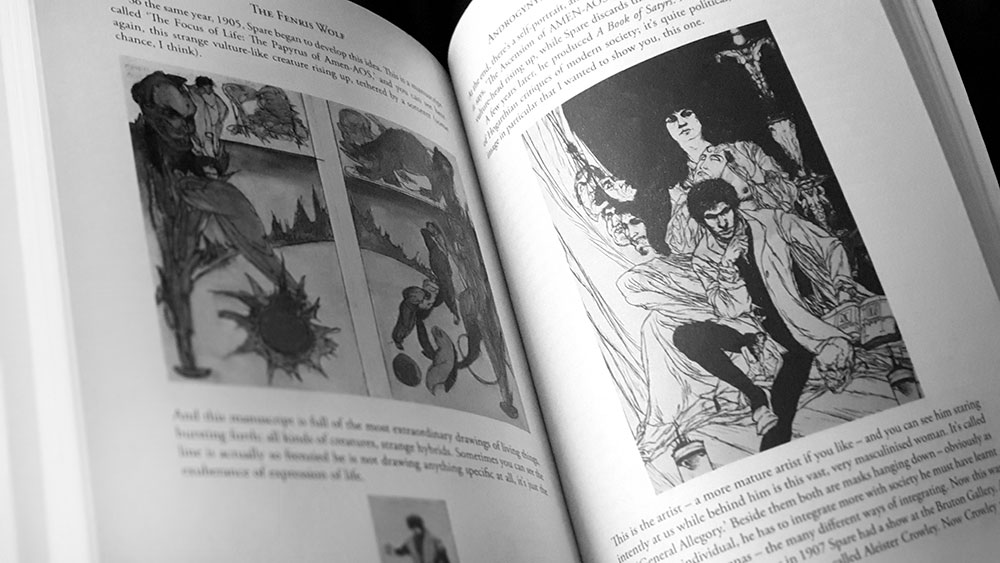

Given the subject matter, two names that spring up repeatedly within the pages of this volume are Sigmund Freud and Austin Osman Spare, with Carl Jung and David Bowie along for the de rigueur ride. The contrast between the dogmatically pragmatic Freud and the mystical Jung is something mentioned across contributions, with Gary Lachman asking in title and body, Was Freud Afraid of the Occult, and Steven Reisner covering similar ground in On the Dance of the Occult and Unconscious in Freud. Meanwhile, in matters of the spiritual and artistic, Spare is a natural touchstone for Balance in Duff’s piece on him, and he can also be found name-checked throughout this volume. The largest consideration of AOS, though, comes from Robert Ansell of Fulgur Press in Androgyny, Biology and Latent Memory, in which he conversationally talks of themes of the androgyne within Spare’s works, drawing from individual pieces, as well as most notably, The Focus of Life.

The line-up of the Psychoanalysis, Art & the Occult conference, as befits its title, drew on artists, occultists and psychologists; with some lucky presenters like editor Vanessa Sinclair going for the trifecta. Perhaps the most, how you say, clinical account comes from Ingo Lambrecht whose Wairua: Following Shamanic Contours hits closest to this reviewer’s geographical location. Lambrecht discusses the use of Te Whare Tapa Wha as a M?ori model for mental health in which the wharenui of the title is comprised of four supporting cornerstones: tinana (physical), hinengaro (mental), wh?nau (family) and wairua (spirit). Wairua is defined here as being an abyss of unmanifested potential comparable to the Ain Soph in Kabbalah, the notion of Zen, and the Via Negativa of Meister Eckhart. Lambrecht shows how a model such as Te Whare Tapa Wha can sit alongside a more materialist psychological one, allowing for an acknowledgement of the sacred and unheimlich. It is worth noting that this is not the only consideration of things from an Aotearoa perspective and artist Charlotte Rodgers in her Stripped to the Core suggests that growing up in a then-isolated New Zealand gave her a magickal edge of sorts.

The more satisfying contributions in The Fenris Wolf 9 are less the considerations of psychology and psychoanalysis and rather those that focus on art and how that intersects with the latter. This is particularly so in instances where artists consider their own work. In a far too brief piece, ending just as you expect it to go further, Ken Henson discusses what as he refers to as the American Occult Revival in his work, connecting his own processes with nineteenth century mesmerism and spiritualism; though it is largely only a singular piece of work, Miss Maude Fealy as Hekate, that he considers in these far too brief pages. In her Proclaim Present Time Over, Val Denham describes how dreams influence her life and work, both visual and aural, presenting the process, as intimated by the William Burroughs and Brion Gysin inspired title, as a magickal act that draws creativity from the subconscious. This is something also explored by Katelan Foisy and Vanessa Sinclair, who are similarly indebted to Burroughs and Gysin and in particular the use of techniques, such as cut-ups, that tap into magickal creativity by disrupting linear time and narrative. Though it is hard to always tell for sure which of the two collaborators are speaking, Sinclair appears to begin first, giving a thorough discussion of the use of cut-ups, emphasising a psychological paradigm concerned with memory as befits her doctorate in psychology, while Foisy takes a more biographical route, describing a series of events and synchronicities concerning the channelling of Burroughs through creative outputs.

This combination of magickal techniques that incorporate the horological and oneiric makes a claim for the preeminent experiential expression of the occult within these pages, drawing on a heady mix of influences from Burroughs, Gysin and Spare. This makes The Fenris Wolf 9 feel very, well, Fenris Wolf, pulling on the same TOPY, chaos magick, Beats and counter cultural strings that can be seen in the journal’s earlier issues. In addition to the examples provided by Sinclair and Foisy, the use of cut-ups reoccur in Fred Yee’s self-evidently-titled Cut-up as Egregore, Oracle and Flirtation Device, in which he namechecks Sinclair and Foisy as teachers and inspiration, reiterating many of their points and techniques. Similarly, the use of dreams already explored by Denham is appraised again by Derek M Elmore, in what is inevitably another consideration of Spare with Dreams and the Neither-Neither. Here, Elmore looks at the themes of love, sex, obsession, unconscious, dreams and death, comparing Spare’s conceptions of them with those in the published works of Freud.

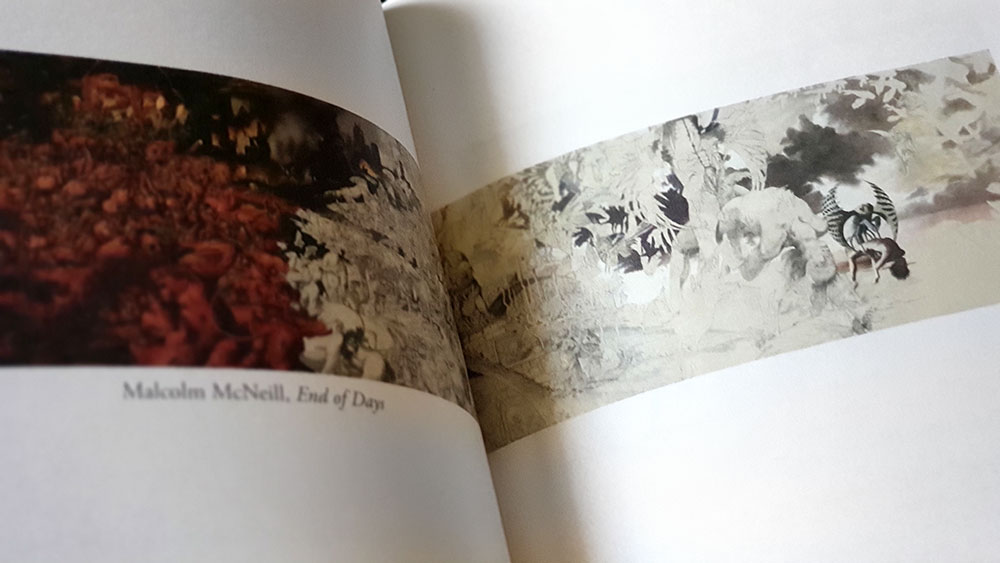

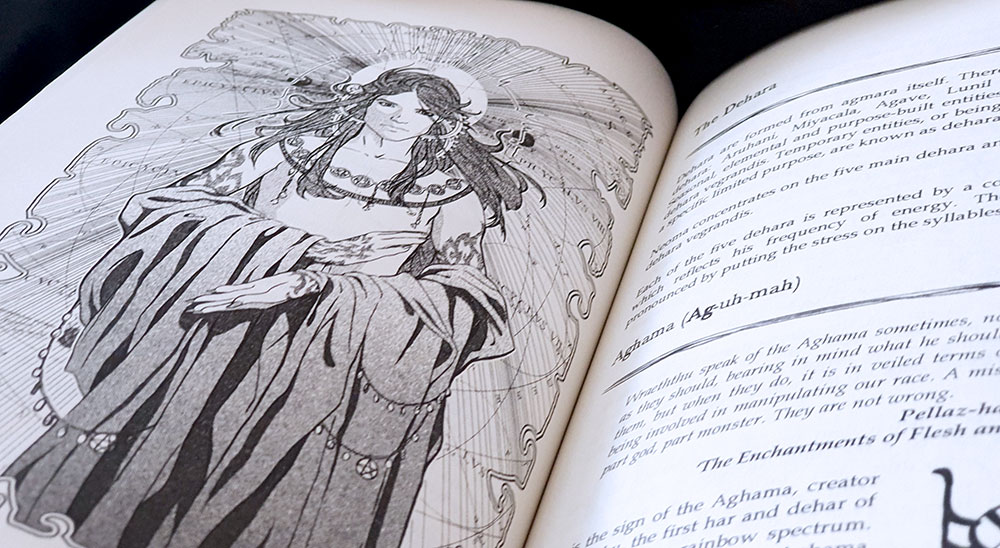

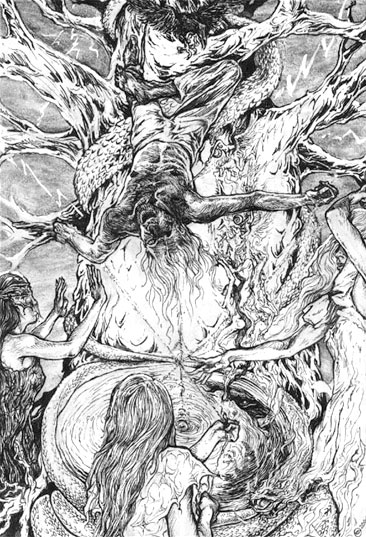

The ninth volume of The Fenris Wolf is a weighty tome at just under 250 pages, with type set in a small point size serif face, surrounded by large margins and a fairly generous footer. Predominantly text-based, in-body illustrations are limited to a few examples where appropriate, while a section of full page images provide examples of the work of Balance, Henson and Malcolm McNeill. Writing quality is overall high, with the dryness of some contributions (and the tiresome spectre of Freud) being offset by the more interesting, chaos and Beats-flavoured ones.

Published by Trapart